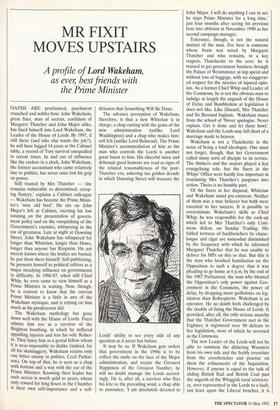

MR FIXIT MOVES UPSTAIRS

as ever, best friends with the Prime Minister

OATHS ARE proclaimed, parchment crunched and nobles bow: John Wakeham, great fixer, man of secrets, confidant of Margaret Thatcher and John Major alike, has fixed himself into Lord Wakeham, the Leader of the House of Lords. By 1997, if still there (and who else wants the job?), he will have logged 14 years at the Cabinet table, a record of Tory survival unequalled in recent times. In and out of influence like the cuckoo in a clock, John Wakeham, the former accountant who came relatively late to politics, has never once lost his grip on power.

Still trusted by Mrs Thatcher — 'she remains vulnerable to determined, creep- ing flattery,' explains a Cabinet colleague — Wakeham has become the Prime Minis- ter's 'wise old bird'. He sits on John Major's left at Cabinet, exerting his low cunning on the presentation of govern- ment policy and on the vanquishing of the Government's enemies, whispering in the ear of greatness. Late at night at Downing Street, John Wakeham has whispered for longer than Whitelaw, longer than Howe, longer than anyone bar Rasputin. He not merely knows where the bodies are buried; he put them there himself. Self-publicising, he presents himself to political editors as a major steadying influence on governments in difficulty. In 1986-87, when still Chief Whip, he even came to view himself as a Prime Minister in waiting. Now, though, he is content to know that the current Prime Minister is a little in awe of the Wakeham mystique, and is relying on him much as his predecessor did.

The Wakeham mythology has gone down well with the House of Lords. Peers admire him too as a survivor of the Brighton bombing, in which he suffered appalling injuries and lost his wife Rober- ta. They fancy him as a genial fellow whom It is near-impossible to dislike (indeed, for all his skulduggery, Wakeham retains only one bitter enemy in politics, Cecil Parkin- son). On top of that, he is seen as a chap with bottom and a way with the ear of the Prime Minister. Knowing their leader has such access is worth gold to peers, whose only reward for long hours in the Chamber is their own self-importance and a self- delusion that Something Will Be Done.

The advance perception of Wakeham, therefore, is that a new Whitelaw is in charge, a chap cutting with the grain of the new administration (unlike Lord Waddington) and a chap who makes him- self felt (unlike Lord Belstead). The Prime Minister's accommodation of him as the man who controls the Lords is another great boost to him. His cheerful mien and debonair good humour are read as signs of the relaxed reasonableness of the post- Thatcher era, ushering ma golden decade in which Downing Street will treasure the Lords' ability to see every side of any question as it never has before.

It may be so. If Wakeham gets orders that government in the 1990s is to be reflect the smile on the face of the Major administration, and secure the Greatest Happiness of the Greatest Number, he will no doubt manage the Lords accord- ingly. He is, after all, a survivor who flies his kite to the prevailing wind, a chap able to announce, '1 am absolutely devoted to

John Major. I will do anything I can to see he stays Prime Minister for a long time,' just four months after seeing his previous boss into oblivion in November 1990 as her second campaign manager.

Tolerance, though, is not the natural instinct of the man. For here is someone whose brain was wired by Margaret Thatcher and who remains, in a key respect, Thatcherite to the core: he is trained to get government business through the Palace of Westminster at top speed and without loss of baggage, with no exaggerat- ed respect for the niceties of injured opin- ion. As a former Chief Whip and Leader of the Commons, he is not the obvious man to indulge at length the anguish of the House of Delay and Bumbledom at legislation it does not like. Like Disraeli, Mrs Thatcher and Sir Bernard Ingham, Wakeham issues from the school of 'Never apologise. Never explain. Get it done and let them howl.' Wakeham and the Lords may fall short of a marriage made in heaven.

Wakeham is not a Thatcherite in the sense of being a loud ideologue. One must not forget, though, that her Government called many sorts of disciple to its service. The thinkers and the orators played a key evangelising role, but the fixers in the Whips' Office were hardly less important in translating Mrs Thatcher's purposes into action. Theirs is no humble part.

Of the fixers at her disposal, Whitelaw and Wakeham stand pre-eminent. Neither of them was a true believer but both were essential to her success. It is possible to overestimate Wakeham's skills as Chief Whip; he was responsible for the cock-up which led to Mrs Thatcher's only Com- mons defeat, on Sunday Trading. His fabled tortures of backbenchers by chaise- longue and cigar are somewhat diminished by the frequency with which he informed Margaret Thatcher that he was unable to deliver his MPs on this or that. But this is the man who lavished humiliation on the Opposition to such a degree that it was pleading to go home at 6 p.m. by the end of the 1987 Parliament; the man who blunted the Opposition's only power against Gov- ernment in the Commons, the power of delay, by dropping more guillotines on leg- islation than Robespierre. Wakeham is an

operator. He no doubt feels challenged by the double of fixing the House of Lords. It provided, after all, the only serious anarchy that the Thatcher Government met in the Eighties; it registered over 90 defeats to her legislation, most of which he reversed in the Commons.

The new Leader of the Lords will not be able to summon the dithering Woosters from his own side and the feebly irresolute from the crossbenches and practise on them the refinements of the Inquisition.

However, if anyone is equal to the task of sliding British Rail and British Coal past the anguish of the Whiggish rural aristocra- cy, over-represented in the Lords to a fault, not least upon the Liberal benches, it is Wakeham. The one task to which he should prove unequal is whipping his mis- tress. Lady Thatcher will make the Lords the exciting part of this Parliament. No less ungovernable should be Lords Tebbit, Ridley and Parkinson. Wakeham's only argument, as one who has described him- self as 'the Minister for Stopping the Gov- ernment Doing Silly Things', will be to imply to them that more good is done by private than public advice. He will get nowhere by this.

He remains, indeed, astonishingly per- sona grata with his former mistress, given his intimacy with her successor. Only Jef- frey Archer seems to have managed a simi- lar feat. Not least is this so given

Wakeham's role on 11 November, 1990. It was he who succeeded in weakening her resolve to fight on by parading the Cabi- net, one by one, through her room in the Commons, each of her ministers giving rein to doubt over her ultimate victory in a manner that was unthinkable had she met them in a group.

Mrs Thatcher, though, has acquitted Wakeham of knavery, suspecting that real skulduggery is to be nailed on the then Chief Whip, the scheming Etonian fop Timothy Renton. Wakeham has been at pains to sing his innocence to MPs. He was, though, in the doghouse for two years after the 1987 Election, with Cecil Parkin- son keen to exclude him from Downing Street once Cecil had regained the PM's affections. (Wakeham had urged Thatcher to dump him in the Sarah Keays affair in 1983.) But in 1989, at the height of the Prime Minister's isolation, he was back as a trusted courtier, having done penance

for his lapse on the BBC's Election Call programme in 1987. In charge of lining up

a rota of ministers for this televised phone- in, he put himself on and (not being a great performer on the wider stage) fluffed it. 'If he couldn't be trusted with some- thing simple like that, could he be trusted with anything else?' says a close colleague.

He is trusted now by Mr Major as Minis- ter in Charge of Government Publicity and, in the last election campaign, was the No. 2 to Christopher Patten at Central Office. He was not altogether successful.

Wakeham was upstairs, out of sight, when William Waldegrave, in desperate trouble over Jennifer's Ear, was downstairs need- ing a chairman. Wakeham did, however, call in Sir Tim Bell and Sir Gordon Reece, a sensible move. The job of news manage- ment was also handed to him during the Gulf war (when he was asked by Mr Major to sit in the four-man War Cabinet) and again during the run-up to the election.

When he was Energy Secretary, he pulled off the coup of privatising electricity to a record 12.5 million buyers before the Government went to the country. This was by no means seen as a sure thing a year earlier. As he contemplates the machinat- ing ahead, it is unlikely to prove Lord Wakeham's last deal at the heart of power.

Previous page

Previous page