DESIGNS ON THE MARKET

Insiders:

a profile of Sir Terence Conran,

successful 'creative retailer'

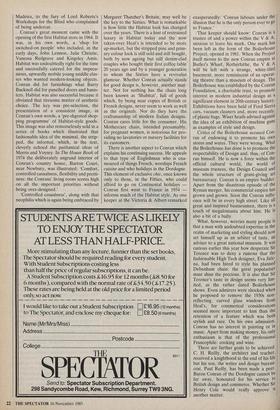

WHEN it was announced last week that the National Economic Development Office is to investigate the standard of design in British manufactures, it came as no surprise that Sir Terence Conran was to be involved. Owing, above all, to the Popularity and influence of his Habitat shops with a wide public, he has become the prince of designers. Knighted, wealthy and very powerful, Conran has made the leap from the world of business to that of official culture; he has succeeded in his ambition to become an insider. It is a phenomenon which, in theory, would not have displeased Prince Albert and Sir Henry Cole, who, long ago, were con- cerned about the quality of design of British manufactured goods and who established what became the Victoria and Albert Museum as an exemplar and a remedy. The significant difference, however, be- tween Prince Albert's day and our own is that in the 19th century there was no doubt about the quality of workmanship of Brit- ish goods. Today there is, and 'design' has become a sort of cosmetic, a matter of superficial styling to make goods more attractive in appearance and therefore more saleable to the undiscriminating. The ambitious type of young man who, a few years back, would have gone into the BBC orbecome an advertising copywriter aspires to be a 'designer', a fashionable 1970s figure wearing designer spectacles with coloured frames, refining the mini- malist design of an angle-poise desk lamp. Sir Terence Conran is both a creator and a product of this phenomenon, but he owes his present power to his undisputed brill- iance as an entrepreneur. The creator of Habitat took over Mothercare — with its 500 shops — in 1982. In 1983 he acquired the chain of Richard Shops. Conran has expanded abroad: there are shops in New York and Paris. Another coup was the acquisition of Heal's, the once-famous store in the Tottenham Court Road which had a deserved reputation for well-made, well-designed furniture earlier this cen- tury. Sir Terence evidently thinks of him- self as a new Ambrose Heal, but he is more of a Gordon Selfridge, in truth more of a businessman than a real designer — a `creative retailer' as he styles himself. A few months back full-page advertisements were taken in newspapers to persuade Debenham's shareholders of the merits of the Conran-Burton takeover bid (ultimate- ly successful). 'Either one of these two men could turn Debenhams around', read the caption under photographs of two remark- ably sinister-looking characters. Sir Ter- ence chose to appear, not like a 'designer' but as a smooth, ruthless, `godfather'-like figure, buttoned into an executive suit and above the modest claim that he is 'arguably the most influential designer, that Britain has yet produced' (Adam? Morris? Mack- intosh?). It was an image which, to stu- dents of Conran's rise and rise, rang true.

To his credit, a good story is told against Conran. 'What is a plagiarist?' asked the eight-year-old daughter of one of Conran's oldest friends. 'I am,' said Conran. He could scarcely deny it. Fiona McCarthy, in her study of the history of British design, long ago pointed out that the Habitat style as 'design' was 'phoney: a brilliant and timely commercial pastiche' of what read- ers of the Architectural Review were en- couraged to admire over 20 years before white enamel ironware, simple earthen- ware jugs and the rest of that look which is a fusion of the late Arts and Crafts movement with Scandinavian puritanism. Conran's success, and it was, at the time, undoubtedly deserved, was to make a rarefied, rather highbrow taste available to a much wider public: 'I am interested in selling good design to the masses.' Con- ran's career shows, yet again, how driving ambition combined with careful plagiarism is irresistible in Britain.

Terence Orby Conran was born in Esher in 1931. What celebrities choose to include or omit in their Who's Who entry is always highly significant. In Conran's case, his famous marriage to Shirley Pearce, who quite matched him in ambition and who, in truth, has brought quite as much lustre to the name of Conran, is simply dealt with by the cryptic 'm; two s.' before 'm. 1963 Caroline Herbert', while no mention is made at all of his parents. A little more information is vouchsafed in the tedious hagiography published last year by Barty Phillips, Conran and the Habitat Story: his father was an importer of gum gopal. Conran was educated at Bryanston which he apparently left under a cloud and then studied textile design at the Central School.

In the early 1950s, Terence Conran was one of several struggling young artists and designers in the then avant-garde, Bohe- mian world of the King's Road, Chelsea. Nor was he the only one to succeed: Mary Quant and the late Laura Ashley were of the same generation, all pioneers of Swing- ing London. Conran first attracted notice as the co-founder of the Soup Kitchen in 1954, which, by its contrived simplicity, so lived up to its name that on the opening night it was taken over by tramps. But his principal work was as a commercial desig- ner and as a salesman of modern furniture. To both a younger and an older genera- tion, the litany of complaint by Conran's against the austerity and stuffiness of post- war Britain seems greatly exaggerated, but conventional Continental modern ideas were certainly striking in London. Conran made furniture and plant stands strongly influenced by the style of the Festival of Britain. One of his early 'designs' was the `Homemaker' plate, decorated with icons of the Fifties — a rubber plant, an amoeba and a coffee table (with wooden balls at the end of its metal legs); another was the conical cane chair on a metal frame. The cane part was simply imported from

Madeira, to the fury of Lord Roberts's Workshops for the Blind who complained of being undercut.

Conran's great moment came with the opening of the first Habitat store in 1964. It was, in his own words, a 'shop for switched-on people' who included, in the early days, John Lennon, Julie Christie, Vanessa Redgrave and Kingsley Amis. Habitat was undoubtedly right for the time and successfully catered for the impecu- nious, upwardly mobile young middle clas- ses who wanted modern-looking objects. Conran did for furnishings what Barry Bucknell did for panelled doors and banis- ters. Habitat was also successful because it obviated that tiresome matter of aesthetic choice. The key was pre-selection, the presentation of a consistent image, in Conran's own words, a 'pre-digested shop- ping programme' of Habitat-style goods. This image was also remorselessly sold in a series of books which illustrated that fashionable idea of the minimal, the strip- ped, the informal, which, in the text, cleverly echoed the puritanical ideas of Morris and Voysey. In The House Book of 1974 the deliberately ungrand interior of Conran's country house, Barton Court, near Newbury, was illustrated: 'Comfort, controlled casualness, flexibility and pretti- ness: the Conrans' living room scores high on all the important priorities without being over-designed.'

`Controlled casualness', along with that neophilia which is again being embraced by Margaret Thatcher's Britain, may well be the key to the Sixties. What is remarkable is how little the Habitat look has changed over the years. There is a hint of restrained luxury in Habitat today and the now taken-over Heal's is intended to be more up-market, but the stripped pine and prim- ary colour look is still sold and still bought, both by now ageing but still denim-clad couples who bought their first coffee table 20 years ago and by a younger generation to whom the Sixties have a revivalist glamour. Whether Conran actually stands for good design is, however, another mat- ter. Not for nothing has the chain long been known as `Shabitat', full of goods which, by being near copies of British or French designs, never seem to work as well as the originals. Nor do they have the craftsmanship of modern Italian designs. Conran cares little for the consumer. His Mothercare chain, intended presumably, for pregnant women, is notorious for pro- viding no lavatories or nursery facilities for its customers.

There is another aspect to Conran which explains his continuing success. He appeals to that type of Englishman who is ena- moured of things French, worships French cuisine and who holidays in the Dordogne. This element of exclusive chic, once known only to those, in the Fifties, who could afford to go on Continental holidays Conran first went to France in 1954 informs much of the Habitat style. As one keeper at the Victoria & Albert-remarked

exasperatedly: 'Conran labours under the illusion that he is the only person ever to go to France.'

That keeper should know: Conran is a trustee of and a power within the V & A, anxious to leave his mark. One mark has been left in the form of the Boilerhouse Project, opened in 1981. When the Project itself moves to the new Conran empire at Butler's Wharf, Rotherhithe, the V & A will be left with a strange, white-tiled basement, more reminiscent of an operat- ing theatre than a museum of design. The Boilerhouse was established by the Conran Foundation, a charitable trust, to promote interest in modern industrial design as a significant element in 20th-century history. Exhibitions have been held of Ford Sierra cars, vacuum cleaners and, more recently, of plastic bags. Wiser heads advised against the idea of an exhibition of machine guns as examples of style and design.

Critics of the Boilerhouse accused Con- ran of endowing it to promote his own stores and wares. They were wrong. What the Boilerhouse has done is to promote the respectability of Design and, thus, of Con- ran himself. He is now a force within the official cultural world, the world of museum trustees, the Design Council and the whole structure of grant-giving art bureaucracy. Conran is an empire builder. Apart from the disastrous episode of the Ryman merger, his commercial empire has grown and grown. Soon the Conran influ- ence will be in every high street. Like all great and inspired businessmen, there is .0. touch of megalomania about him. He Is also a bit of a bully.

What, however, worries many people is that a man with undoubted expertise in the realm of marketing and styling should now set himself up as an arbiter of taste, an adviser to a great national museum. It was curious earlier this year how desperate Sir Terence was to deny a rumour that the fashionable High Tech designer, Eva Jiric- na, had been hired to style his planned Debenham chain: the great popularises must shun the precious. It is also that Sir Terence's taste in design seems very lim- ited, as the rather dated Boilerhouse shows. Even admirers were shocked when he proposed to remove the 1930s non- reflecting, curved glass windows front Heal's, for commerical considerations seemed more important to him than the retention of a feature which was both stylish and rare. On his own admission, Conran has no interest in painting or 10 music. Apart from making money, his only enthusiasm is that of the professional Francophile: cooking and wine.

There are further goals to be achieved. C. H. Reilly, the architect and teacher, received a knighthood at the end of his life but his son, the writer and design bureau- crat, Paul Reilly, has been made a peer. Baron Conran of the Dordogne cannot be far away, honoured for his service to British design and commerce. Whether sir Henry Cole would really approve Is another matter.

Previous page

Previous page