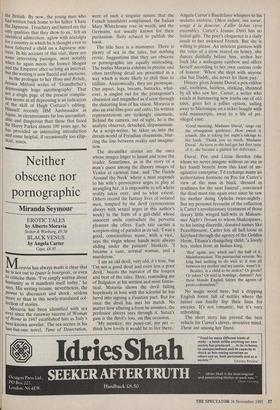

Neither obscene nor pornographic

Miranda Seymour

EROTIC TALES by Alberto Moravia

Secker & Warburg, £9.50

BLACK VENUS by Angela Carter

Cape, f8.95

Moravia has always made it clear that i he is not out to epater le bourgeois, or even to criticise them. 'I've simply written about humanity as it manifests itself today,' he says. His writing retains, nevertheless, the Power to disconcert and shock, seldom more so than in this newly-translated col- lection of stories.

Moravia has been identified with sex ever since the runaway success of Woman of Rome in 1947 established him as Italy's best-known novelist. The sex-scenes in his ast-but-one novel, Time of Desecration, were of such a singular nature that the French translators complained, the Italian Mary Whitehouse rose in wrath, and the Germans, not usually known for their puritanism, flatly refused to publish the book.

The title here is a misnomer. There is plenty of sex in the tales, but nothing erotic. Suggestions that they are obscene or pornographic are equally misleading. The bodies Moravia exhibits in precise and often terrifying detail are presented in a way which is more likely to chill than to titillate. Anatomically, they are grotesque. One aspect, legs, breasts, buttocks, what- ever, is singled out for the protagonist's obsession and magnified as if seen through the distorting lens of his vision. Moravia is also an avid film-goer and critic; his written representations are strikingly cinematic. Behind the camera, out of sight, he is the analytic observer, detached, dispassionate. As a script-writer, he takes us into the dream-world of Freudian obsessions, blur- ring the line between reality and imagina- tion.

The dreamlike stories are the ones whose images linger to haunt and tease the reader. Sometimes, as in the story of a man's quest among the illusory images of Venice at carnival time, and 'The Hands Around the Neck' where a man responds to his wife's provocative urges to play at strangling her, it is impossible to tell where reality takes' over, and to what extent. Others record the fantasy lives of isolated men, tempted by the devil (synonymous always with sexual urges in this author's work) in the form of a girl-child whose innocent smile contradicts the perverse pleasure she offers. Each tale carries a scorpion-sting of paradox in its tail. 'I was a good, conscientious nurse; with a vice,' says the virgin whose hands were always sliding under the patients' blankets. 'I became a sane, normal woman, and a murderess.'

'I am an old devil, very old, it's true, but 'I'm not a good devil and even less a poor devil,' boasts the narrator of the longest and best of the tales. Here, reminding me of Bulgakov at his wittiest and most fantas- tical, Moravia shows the devil falling hopelessly in love with the scientist he has lured into signing a Faustian pact. But for once the devil has met his match. No matter how alluring a form he assumes, the professor always sees through it. Satan's gain is the devil's loss, on this occasion.

'My monkey, my pussy-cat, my pet think how lovely it would be to live there,' Angela Carter's Baudelaire whispers to his mulatto mistress. (Mon enfant, ma soeur, songe a la douceur, d'aller Id-bas vivre ensemble). Carter's Jeanne Duvl has no lyrical gifts. The poet's eloquence is a daily insult to her awkward French. But she is willing to please. An indolent giantess with the voice of a crow reared on honey, she dances dutifully before him, arches her back like a mahogany rainbow and offers herself according to her own curious code of honour: 'When she slept with anyone else but Daddy, she never let them pay.' History gives Jeanne Duval a pox-ridden end, toothless, hairless, stinking, shunned by all who saw her. Carter, a writer who excels at hammering new truths out of old tales, gives her a jollier option, sailing away to Martinique on a ticket bought with sold manuscripts, away to a life of pri- vileged ease:

'Good morning, Madame Duval,' sings out the obsequious gardener. How sweet it sounds. She is taking last night's takings to the bank. 'Thank you so much, Madame Duval.' As soon as she had got her first taste of it, she became a glutton for deference.'

Duval, Poe and Lizzie Borden (she whom we never imagine without an axe in her hand) benefit from this kind of im- aginative enterprise. I'd exchange many an authoritative footnote on Poe for Carter's view of the man in black 'dressed in readiness for the next funeral', convinced the dead must rise again ever since he saw his mother doing Ophelia twice-nightly. But my personal favourite of the collection is Carter's revolutionary treatment of those dreary little winged half-wits in Midsum- mer Night's Dream to whom Shakespeare, to his lasting discredit, donated names like Peaseblossom. Carter lets all hell loose in fairyland through the agency of the Golden Herm, Titania's changeling child, 'a lovely boy, stolen from an Indian king.'

'Boy' again, see; which isn't the half of it. Misinformation. The patriarchal version. No king had nothing to do with it; it was all between my mother and my auntie, wasn't it.

Besides, is a child to be stolen? Or given? Or taken? Or sold in bondage, dammit? Are these blonde English fairies the agents of proto-colonialism?'

No magic wood here, but a dripping English forest full of nettles where the fairies can hardly lisp their lines for sneezes. It's not romantic, but it's very refreshing.

The short story has proved the best vehicle for Carter's clever, inventive mind. These are among her finest.

Previous page

Previous page