ARTS

Progress through diversity

Felicity Owen on the Courtauld Institute of Art, Britain's leading art historical centre The Courtauld Institute of Art, housed since 1989 in the handsome north block of Somerset House in the Strand, enjoys world-wide renown as the leading art his- torical centre in Britain. Its Gallery includes the largest collection of high-qual- ity Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings in this country. Yet while the National Gallery and Tate Gallery (with Courtauld alumni in key positions) have gained ever greater prominence, the Cour- tauld's image as a showplace of art remains blurred; the annual attendance at its Gallery is less than half that of the recent short-run Degas exhibition in the National Gallery's unwelcoming basement.

The Courtauld was the first British institute to teach art history, and was the brainchild of Viscount Lee of Fareham, a patriotic but disappoint- ed politician who gave Chequers to the nation. In 1931, he persuaded a fellow enthusiast, Samuel Courtauld, the artificial silk millionaire, to endow the University of London with the institute that now bears his name. Shortly afterwards, as a memorial to his wife, Courtauld made over the remaining lease of his Portman Square house so that stu- dents and art lovers could enjoy a beautiful 18th-century ambience with his favourite Manets, Monets and Renoirs still on the walls. A gift of £70,000 should have provided a building in Bloomsbury to house the Institute. Instead, after his death in 1947 and the difficulties of the post- war years, the paintings were shown in Woburn Square and have only recently been united with the aca- demic Institute at Somerset House.

Now, after a painful phase while the Institute eased itself into Sir William Chambers's grandest 18th- The Co century building, the Courtauld is getting a new lease of life. Under the firm leadership of Professor Eric Fernie, with an impressive young staff and John Mur- doch in charge of the Gallery, sights are set on turning Somerset House into a major arts complex. The Government has decided to move the Inland Revenue from the south block possibly allowing 20th-century paintings to be shown on the floor approached by the famous Navy staircase, the vaults being allocated the Gilbert Col- lection of gold and silver, a recent £75 mil- lion gift to the nation. Cars in the courtyard will give way to 18th-century sculpture lending the quadrangle a Parisian feel, and a final touch could be the opening of a restaurant on the magnificent south terrace overlooking the Thames. urtauld's 'Self-portrait with Bandaged Ear' by va n Gogh As a first step, some £2.5 million, largely Lottery money, will go towards an air-tem- pering system in the present exhibition rooms, famous in Georgian times as the home of the Royal Academy and more recently for the insensitive treatment it received from designers and heating engi- neers. The beautiful staircase, so often fea- tured with a jostling crowd in Rowlandson's watercolours, will be amongst parts restored to pristine condi- tion; and in celebration Westminster Coun- cil has agreed that the Courtauld can advertise its presence with flags.

Until 5 January, in the old Academy's Great Room, there is the Chambers bicen- tenary exhibition, a reminder of the archi- tect's international credentials that led to royal patronage and power in the Academy behind the popular Sir Joshua Reynolds. The walls once again stacked high with 18th-century works look splendid but, when the galleries close at a date in 1997 for a year of refurbishment, hopefully they will be given a new look more sympathetic to the late 19th-century French pictures of the permanent collection — the hang in the Orsay Museum being proof that all is possi- ble.

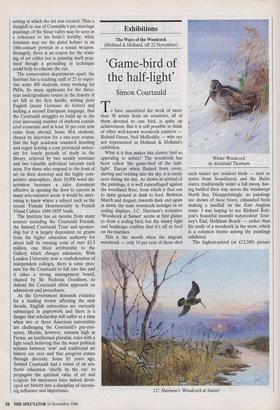

With Manet's 'Bar at the Folies-Berere' (recently the subject of a whole book), Gauguin's 'Haymaking' and Tahitian scenes, Cezanne's 'Lac d'Annecy' and 'Montagne Sainte-Victoire', van Gogh's `Self-portrait with Bandaged Ear' and four vintage works by Degas to mention only a few, there is a great opportunity for the Cour- tauld to project a high profile as the British centre for this kind of paint- ing, complementing the National Gallery which is retrieving its pre- 1900 Impressionists and Post- Impressionists from the Tate in an exchange. The debt owed to Cour- tauld for introducing what he termed `modern' masters to a reluctant John Bull is manifest, so many of these paintings in the national collection having been acquired with his 1923 gift of £30,000.

The Institute's equally distin- guished works of earlier periods include two 14th-century altarpieces by Bernardo Daddi and the Master of Flemalle's early 15th-century trip- tych, this from Count Antoine Seil- em's bequest that offers no fewer than 30 oils by Rubens while Lee left the perfect, small 'Adam and Eve' by the elder Cranach and Botticelli's `Holy Trinity'. The British section includes Gainsborough's sensitive portrait of his wife and a fine selec- tion of prints, drawings and watercolours, not forgetting bequests by Roger Fry and others of 20th-century works.

The Witt and Conway photographic libraries — a well-hidden international resource open to all corners — share nearly 3 million images of art and architecture respectively. These, the collection and the reference library are at the heart of the Institute that attracts the finest scholars in Western art from antiquity to today. Where emphasis used to be on Renaissance stud- ies, the range is now far wider, and a three- year course in the history of American art has been privately funded.

The approach too is more varied, purvey- ors of 'new' art history being less con- cerned with connoisseurship than the setting in which the art was created. Thus a dunghill in one of Constable's pre-marriage paintings of the Stour valley may be seen as a reference to his bride's fertility, while feminists may see the pistol holster in an 18th-century portrait as a sexual weapon Strangely, there is no course for the train- ing of art critics nor is painting itself prac- tised though a grounding in technique could help to educate the eye.

The conservation departments apart, the Institute has a teaching staff of 25 to super- vise some 400 students, some working for PhDs. So many applicants for the three- year undergraduate course in the history of art fall at the first hurdle, writing poor English (many Germans do better) and lacking a second European language, that the Courtauld struggles to build up to the ever increasing number of students consid- ered economic and at least 10 per cent now come from abroad. Some MA students, chosen by interview for a one-year course, find the high academic standard daunting and regret leaving a cosy provincial univer- sity for lonely periods of study in the library, relieved by two weekly seminars and two valuable individual tutorials each term. For those who respond to the feast of art on their doorstep and the highly com- petitive atmosphere, their 10,000 word dis- sertation becomes a sales document effective in opening the door to careers in many arts-oriented areas: it would be inter- esting to know where a subject such as the recent 'Female Homosociality in French Visual Culture 1848-1859' leads.

The Institute has an income from many sources including the Courtauld Friends, the Samuel Courtauld Trust and sponsor- ship but it is largely dependent on grants from the higher education authority for about half its running costs of over £3.3 million, one third attributable to the Gallery which charges admission. With London University now a confederation of independent colleges, there is some pres- sure for the Courtauld to fall into line and it takes a strong management board, chaired by Sir Nicholas Goodison, to defend the Courtauld elitist approach on admissions and procedures.

As the Government demands evidence for a funding review affecting the next decade, English universities are currently submerged in paperwork and there is a danger that scholarship will suffer at a time when two or three American universities are challenging the Courtauld's pre-emi- nence. Morale, however, remains high as Fernie, an intellectual pluralist, rules with a light touch believing that the worst political schisms between 'new' and traditional art history are over and that progress comes through diversity. Some 65 years ago, Samuel Courtauld had a vision of an aes- thetic education 'chiefly by the eye' to propagate the spiritual value of art and religion: his successors have indeed devel- oped art history into a discipline of increas- ing influence and importance.

Previous page

Previous page