ARTS

Exhibitions

Buried treasure

Giles Auty

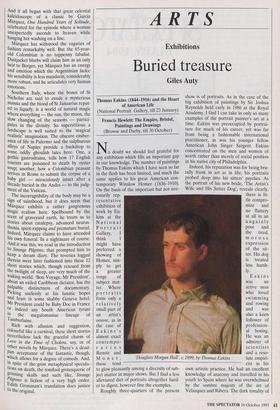

Thomas Eakins (1844-1916) and the Heart of American Life (National Portrait Gallery, till 23 January) Francis Hewlett: The Empire, Bristol, Paintings and Drawings (Browse and Darby, till 30 October)

No doubt we should feel grateful for any exhibition which fills an important gap in our knowledge. The number of paintings by Thomas Eakins which I have seen so far in the flesh has been limited, and much the same applies to his great American con- temporary Winslow Homer (1836-1910). On the basis of the important but not nec- essarily rep- resentative exhibition of work by Ea- kins at the National Portrait

Gallery, I think might have preferred a showing of Homer, sim- ply to get a greater range of subject mat- ter. Where portraits form only a relatively small part of

an artist's oeuvre, as in the case of Eakins's almost exact contempo- raries Renoir and Monet, these tend

Douglass Morgan Hall; c. 1899, by Thomas Eakins to glow pleasantly among a diversity of sub- ject matter in major shows. But I find a less alleviated diet of portraits altogether hard- er to digest, however fine the examples.

Roughly three-quarters of the present

show is of portraits. As in the case of the big exhibition of paintings by Sir Joshua Reynolds held early in 1986 at the Royal Academy, I find I can take in only so many examples of the portrait painter's art at a time. Eakins was preoccupied by portrai- ture for much of his career, yet was far from being a fashionable international practitioner, as was his younger fellow American John Singer Sargent. Eakins concentrated on the men and women of worth rather than merely of social position in his native city of Philadelphia.

Eakins

was an active man who loved swimming and rowing and was also a keen follower of profession- al boxing. He was an admirer of scientists and a reso- lute empiri- cist in his

own artistic practice. He had an excellent knowledge of anatomy and travelled in his youth to Spain where he was overwhelmed by the sombre majesty of the art of Velazquez and Ribera. The dark tonality of Spanish painting stayed with him, but he owed more psychologically to the tradition of Rembrandt. In short, Eakins was a humane realist rather than an absolutist in anything; he was not formally religious yet made friends with and painted a number of Roman Catholic dignitaries with whom he felt intellectual kinship. For those of us unable to travel in the USA as often or extensively as we might wish, the present exhibition is a boon. Indeed, I would welcome opportunities to see far more late-19th-century art than we do in Britain from countries other than France: from the USA certainly, but also from Italy, Denmark and notably Germany. To the best of my knowledge there has never been a major exhibition here of the art of Adolf von Menzel (1815-1905), who was highly regarded by Degas and was one of the finer German artists of the century. Our historical understanding of the art of the 19th century as a whole is coloured excessively still by the contributions artists supposedly made to the development of modernism — which has proved a far from unmitigated benefit. Even the more thoughtful historians, critics and adminis- trators tend to push this view as though in the grip of some knee-jerk reflex. I can but beg them to consider history more broadly.

On weeks in which major exhibitions at Public galleries open in London, any exhi- bitions of a more minor nature, however excellent, tend to suffer critical neglect. Yet if the latter happened to open on dif- ferent dates they would often be welcomed by critics who found themselves short of good material. This operation of chance is unfortunate especially if, as in the case of Francis Hewlett, we are looking at the results of years of highly intensive and intelligent work. When Hewlett was an art student at Bris- tol he obtained permission to draw as often as he liked in the old Bristol Empire the- atre. Back in 1949, closely observed, realis- tic drawing from the object was still encouraged and Hewlett made scores of detailed drawings of a music-hall venue which has been demolished for more than 30 years now, determining to work these up one day into grand paintings. This particu- lar 'day' took more than 40 years to arrive but the final results are spectacular, taxing the knowledge the artist acquired over those intervening years to the full. The best of the finished works are remarkable and should find their way into public collections not so much for their wealth of historical detail as for their status as ambitious and highly complex works of art. With current attitudes to teaching it is unlikely that any present-day art student would begin to know how to make the kind of initial drawings on which these paintings of times past are based. Such works are relics of history now — and so is the kind of wise instruction by tutors and genuinely open artistic ambience that made them possible.

Previous page

Previous page