BOOKS

Boy's own story

David Hughes

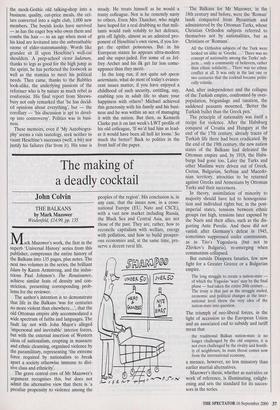

LIFE IN THE JUNGLE: MY AUTOBIOGRAPHY by Michael Heseltine Hodder, £20, pp. 560 Yes, but what is he like? A political memoir is rarely kiss, let alone tell. They are written to set the record straight, to put posterity in the know, to correct future his- torians on their interpretation of momen- tous events, to bow out on a dignified but deafening ovation of well-chosen words but rarely to reveal the man. Without read- ing everyone else's apologia, a formidable task in an era when most politicians lack both style and eloquence, I find it impossi- ble to judge who makes the best case for anyone's responsibility for the last two decades of crisis or triumph, let alone who is right about them. Let the politicos argue it out, while we look for the man behind the current evidence of this book.

While I was editing Isis at Oxford, Michael (two years younger) was several rungs up the ladder to the Union presiden- cy. With sly fun we recognised each other as ruthless careerists plotting to take the future by storm, as well as small boys play- ing games with the present. We took it for granted, with suitable shyness, that we were top-notch. Our relations were charac- terised by warmth and humour, two quali- ties not invariably associated with his later image in power, but valuable and inspirit- ing when in 1960 he appointed me editor of Town magazine, which he owned jointly with Clive Labovitch Ca kind, gentle man whom I trusted implicitly'). Into a crowded little office in Soho were packed his multi- ple business interests. As editor I shared a hutch with a building contractor. For con- ferences on strategy, also known as lunch, Michael, Clive and I traipsed across to the Carvery at the Regent Palace, from an upper window of which hotel overlooking Piccadilly Circus the teenage Heseltine watched London's relief and happiness besieging Eros on VJ Day: 'a moment of history, hopefully never to be repeated, engraved for ever on my memory'. Quite a lot of lumps in the throat arise in this otherwise even (and now and then racy) narrative.

Also engraved on his memory are his own moments of history, and although he is properly proud of them they show a limited view of the man within. He busily promot- ed Concorde when Minister for Aerospace. With tremendous aplomb he inspired a hostile Merseyside to clean up the toxic mess and renew its self-confidence along with its architecture. At Environment he was the force behind Canary Wharf and the regeneration of the South Bank. He believes it was his 'management style' that kept inducing the Iron Lady to promote him, finally (in her administration) to Defence Secretary; certainly few indica- tions hover over these pages of any love lost between them. In these later chunks of book the man himself disappears in a welter of policies; Hezza dissolves into issues; Tarzan facelessly swings into action.

The essence of the fellow emerges often in his compliments to others, but even then no more than formally. Keith Joseph 'had a brilliant mind, an unswerving integrity and a rigorous commitment to any conclusions that he reached'. His wife Anne (to whom the index contains but ten references) 'has always been there, a tower of strength and unswervingly loyal'. The platitudes, unweeded by Tony Howard who tended the prose and dug out the dyslexia, do not conceal Michael's kindness or the reflec- tion of himself he unwittingly conveys in these tributes. None of his friends puts in more than a ghostly appearance. So we must look earlier into frequently amusing pages for clues to the vigour of the inner man, for whom politics (jealous taskmistress') provided a carapace and commercial proactivity a disguise.

The first surprise is to discover that this Nordic blond was born a Franco-Welsh Englishman, which helps explain why in 1960 he put unresisted pressure on me as his editor to publish in Town an enlight- ened article on the urgency of European integration, from which vision he has sig- nally failed to swerve. Brought up in Swansea, with the natural magic of the Gower peninsula to feed on, he felt 'that overwhelming fascination with nature which has stayed with me ever since'. He credibly believes his concern for the envi- ronment drew its energy from the coastal beauty of Gower, for which in 1959 he stood as Tory candidate. He notes too that Swansea's vortex of industry, class division, human warmth and breathtaking hinter- land implanted in his brain the notion of One Nation Conservatism. On the family's postwar two acres in a good suburb of that vibrant city, where his love of gardening rooted, he formed a company with two other boys to sell their scrub-clearing services to his father at five bob an hour: business was born.

Meanwhile he formed the Tit Club of twitchers; his one intimate confession in the entire volume is that he, as the boss, was called Great Tit. He ringed wild birds and released them into the void as if send- ing out manifestos. Jackdaws, even a vari- ety of finches, were tamed to sit on the palm of his hand like a captive audience. He pursued his interest in birds to Shrews- bury where his collection grew as his aca- demic performance shrank. Out of this addiction to nature sprang eventually the arboretum he planted on 50 acres of Northants, which with modest propriety he is convinced will be his true and more telling memorial. Meanwhile, straying into the mean streets of his old school town, the schoolboy saw a poor little spitting image of his sister Bubbles: a memory, also sharply engraved, that helped to forge the political ideal of working with, and for, those less fortunate than oneself. In the nick of time he manages to snatch back sentiment from sentimentality.

Heseltine, M R D, was no leader at school. Low in the hierarchy, he was only a study monitor in that microcosm. By a whisker he failed to win millions on the pools as a lad. His presidency of the Oxford Union was shadowed by his friends having gone down. He stayed up an extra term to fill that office, but brilliantly turned the mock-Gothic old talking-shop into a business: quality, cut-price meals, the cel- lars converted into a night club, 1,000 new members. The boyish looks have survived — as has the eager boy who owns them and combs the hair — to an age when most of his kind are levitated into the unbreathable ozone of elder-statesmanship. Words like grandee sit ill upon Heseltine's well-cut shoulders. A prep-school victor ludorum, thanks to legs as good for the high jump as the sprint, he has perfected the footwork as well as the stamina to meet his political needs. Then came, thanks to the Bubbles look-alike, the underlying passions of the reformer who is by nature as much rebel as conformist. His final report from Shrews- bury not only remarked that 'he has decid- ed opinions about everything', but — the corollary — 'his discussion is apt to devel- op into controversy'. Politics was in busi- ness.

These memoirs, even if 'My Autobiogra- phy' seems a vain tautology, seek neither to vaunt Heseltine's successes (well, a bit) nor justify his failures (far from it). His tone is steady. He treats himself as he would a trusty colleague. Nor is he remotely nasty to others. Even Mrs Thatcher, who might have hoped for a real drubbing so that mili- tants would rush volubly to her defence, gets off lightly, almost as an admired pro- ponent of Heseltine's own views, if you for- get the epithet poisonous. But in his European stance he appears ultra-modern and she super-jaded. For some of us Jef- frey Archer and his ilk get far less come- uppance than they merit.

In the long run, if not quite sub specie aeternitatis, what do most 'of today's evanes- cent issues matter, if you have enjoyed a childhood of such security, entitling, nay, enabling you in adult life to share your happiness with others? Michael achieved this generosity with his family and his busi- ness and he was within an ace of managing it with the nation. But then, as Kenneth Clarke put it on last week's LWT profile of his old colleague, 'If we'd had him as lead- er it would have been all hell let loose.' So much the better? Back to politics in the front half of the paper.

Previous page

Previous page