Photography Towards a Bigger Picture, Part II (V & A,

till 15 January) Eye-

Francis Hodgson

Being a museum curator is one of those difficult professions in which the skilful marshalling of other people's talents pro- duces a structured whole which is too rarely acknowledged as the marshal's own — like conducting an orchestra. In To- wards a Bigger Picture, Mark Haworth- Booth, responsible for photography at the V & A, has made an exhibition which impels unstinting admiration for him and what he has put together even before it asks us to admire any individual work. The clarinettist may well be playing out of his skin, but it is the whole orchestra that we hear.

The first part of the exhibition was shown in the summer of 1987. It contained Helen Chadwick's 'One Flesh', which should have won her the Turner Prize on its own, a masterpiece of confident re- examination of mediaeval iconography, a modern madonna made in beautifully man- ipulated collage of coloured photocopies. One or two other pieces in that part of the exhibition before the interval caught the eye: I would single out Garry Miller's triptych of three straight reeds in gently progressing decay, photographed without a camera like the plant-photographs cyanotyped (blueprinted) by Anna Atkins more than a hundred years before.

But only with this second part of the exhibition is it clear just how carefully Haworth-Booth was treading. The pictures seem to have little in common. Yet together they make a coherent whole which is informatively pedagogical and at the same time quite obviously a personal and idiosyncratic choice. Whatever the merits and demerits of the photographs themselves, it is a curator's achievement of total mastery.

There are advertising photographs and landscapes, photographs masquerading as reportage and photographs masquerading as art. There are photographs overlaid with paint, and photographs which offer only the slick surface of their own light-sensitive emulsion. Another Helen Chadwick, `Vanitas', is less successful than the first. It seems to overdo its effect by asking the viewer to turn around and notice a part of it (a mirror) separated from the rest of his own person. David Pizzanelli's `Muybridge Animation' is a small piece of highly polished metal, about the size of a post- card. It hardly looks like a photograph at all until we remember the daguerreotype of which we will hear so much in 1989, the year which has rather arbitrarily been designated as the 150th anniversary of the birth of photography. It is in fact a holo- gram re-creation of one of Muybridge's pictorial series on Animal Locomotion. So it is a version of Muybridge in colour, strangely appropriate now that old movies are threatened with re-tinting. It is also a movie whose effect can only be seen when the viewer moves. Its tribute to Daguerre is timely, but so is the unabashed way in which it takes its inspiration from photo- graphy's own past. It has taken a long time, but photographers know how to do that now. Which means simply that they no longer have to start afresh each time.

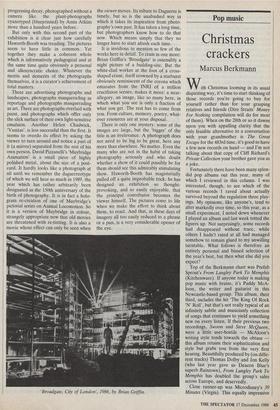

It is invidious to mention so few of the works here in detail. To cram in one more: Brian Griffin's 'Broadgate' is ostensibly a night picture of a building-site. But the white-clad worker at the foot of a cross- shaped crane, itself crowned by a starburst obviously reminiscent of the corona which emanates from the INRI of a million crucifixion scenes, makes it more: a near- allegory, an image, like so many here, in which what you see is only a fraction of what you get. The rest has to come from you. From culture, memory, poetry, what- ever resources are at your disposal.

There is only one mystery: some of the images are large, but the 'bigger' of the title is an irrelevance. A photograph does not need to be big to be great, here any more than elsewhere. No matter. Even the many who are not in the habit of taking photography seriously and who doubt whether a show of it could possibly be for them should see this admirably stimulating show. Haworth-Booth has magisterially pulled off a quite improbable trick: he has designed an exhibition so thought- provoking, and so easily enjoyable, that the principal contributor becomes the viewer himself. The pictures come to life when we make the effort to think about them, to react. And that, in these days of imagery all too easily reduced to a phrase or a pun, is a very considerable opener of the eye.

'Broadgate, City of London', 1986, by Brian Griffin.

Previous page

Previous page