THE CRACKS IN THE ICON OF GORBACHEV

Mr Gorbachev has appointed himself the evangelist ' earthquake has shown up his weakness and intolerance

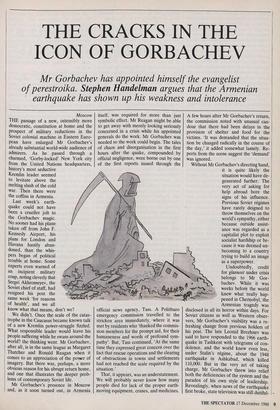

Moscow THE passage of a new, ostensibly more democratic, constitution at home and the prospect of military reductions in the Soviet colonial machine in Eastern Euro- pean have enlarged Mr Gorbachev's already substantial world-wide audience of admirers. As he passed through a charmed, `Gorby-locked' New York city from the United Nations headquarters, history's most seductive Kremlin leader seemed to levitate above the melting slush of the cold war. Then there were the coffins in Armenia.

Last week's earth- quake could not have been a crueller jolt to the Gorbachev magic. No sooner had his plane taken off from John F. Kennedy Airport, his plans for London and Havana hastily aban- doned, than the whis- pers began of political trouble at home. Some experts even warned of an incipient military coup, noting cleverly that Sergei Akhromeyev, the Soviet chief of staff, had resigned his post the same week 'for reasons of health', and we all know what that means, don't we?

We didn't. Once the scale of the catas- trophe in the Caucasus became known talk of a new Kremlin power-struggle fizzled. What responsible leader would leave his people suffering while he swans around the world? the thinking went. Mr Gorbachev, after all, is in the same league as Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan when it comes to an appreciation of the power of imagery. But there was, perhaps, a more obvious reason for his abrupt return home, and one that illustrates the deeper prob- lems of contemporary Soviet life.

Mr Gorbachev's presence in Moscow and, as it soon turned out, in Armenia itself, was required for more than just symbolic effect. Mr Reagan might be able to get away with merely looking seriously concerned in a crisis while his appointed generals do the work. Mr Gorbachev was needed so the work could begin. The tales of chaos and disorganisation in the first hours after the quake, compounded by official negligence, were borne out by one of the first reports issued through the official news agency, Tass. A Politburo emergency commission travelled to the stricken area immediately, where it was met by residents who 'thanked the commis- sion members for the prompt aid, for their humaneness and words of profound sym- pathy'. But, Tass continued, 'At the same time they expressed great concern over the fact that rescue operations and the clearing of obstructions in towns and settlements had not reached the scale required by the situation.'

That, it appears, was an understatement. We will probably never know how many people died for lack of the proper earth- moving equipment, cranes, and medicines. A few hours after Mr Gorbachev's return, the commission noted with unusual can- dour that there had been delays in the provision of shelter and food for the victims. 'It was demanded that the situa- tion be changed radically in the course of the day,' it added somewhat lamely. Re- ports from the scene suggest the 'demand' was ignored.

Without Mr Gorbachev's directing hand, it is quite likely the situation would have de- generated further. The very act of asking for help abroad bore the signs of his influence. Previous Soviet regimes have rarely deigned to throw themselves on the world's sympathy, either because outside assist- ance was regarded as a capitalist plot to exploit socialist hardship or be- cause it was deemed un- becoming to a country trying to build an image as a superpower. '

Undoubtedly, credit for glasnost under crisis belongs to Mr Gor- bachev. While it was weeks before the world knew what eally hap- pened in Cheinobyl, the Armenian tragedy was disclosed in all its horror within days. For Soviet citizens as well as Western obser- vers, Mr Gorbachev's visibility was a re- freshing change from previous holders of his post. The late Leonid Brezhnev was said to have responded to the 1966 earth- quake in Tashkent with telegrams of con- dolence, and the world knew even less, under Stalin's regime, about the 1948 earthquake in Ashkabad, which killed 110,000. But in the very act of taking charge, Mr Gorbachev threw into relief both the deficiencies of the system and the paradox of his own style of leadership. Revealingly, when news of the earthquake first broke, state television was still dutiful- ly reporting Mr Gorbachev's UN speech.

As the week wore on, the personal strain placed on him by the necessity of being all things to all men became painfully obvious. Interviewed by Soviet television as he wrapped up a two-day tour of the earth- quake zone, Mr Gorbachev was close to tears. 'It is unbearable to see so many people suffering,' he said. 'I find it hard even to talk about it.' Moments later, prodded by a Soviet journalist about re- ports of continued nationalist unrest in the region, he launched a bitter attack against 'carpetbaggers' and 'power-hungry' protes- ters that revealed a side of his personality rarely seen in public.

His outburst, which seemed bound to exacerbate local anxieties rather than soothe them, showed the frustrations of his self-appointed role as national evangelist. Since he came to office, he has been preaching the good news of perestroika from every available pulpit. In the past year alone, he has probably spent more hours sermonising in public than most politicians do in a lifetime. He can be heard one day urging farmers and workers to take back control of their lives from party bureaucrats, and the next day warn- ing Estonians and Latvians against the sin of taking freedom too far. As the system has shown little sign of budging, he has come to rely more and more on the force of his own personality to get things done, and to display intolerance towards those who will not see it his way. Such personalised leadership, as the revolutionaries who con spired against the tsar 70 years earlier well knew, is a lightning rod for discontent.

Mr Gorbachev, needless to say, has disclaimed any desire to use the 'whip' as he puts it, of tsarism or, to be more relevant, of Stalinism. His journey to New York, where, among other events, he allowed himself to be photographed with the Statue of Liberty as a backdrop, display- ed his eagerness to relax the ideological competition with the West and, by implica- tion, ease the restrictions at home which have arisen from that competition. He is the first Soviet leader to appear truly at home with capitalist leaders. But his en- counters abroad can only have accentuated his despair at the awesome incompetence of the rigidly centralised machinery of his own government. Working around the clock to organise earthquake relief and reconstruction must have revealed to him, as it did to the rest of the world, how few real inroads perestroika has made outside Moscow.

In coming to such a conclusion, he would not have been alone. There is, remarkably, a growing sense of national shame in the aftermath of the earthquake over the lack of planning and basic precautions, which in some cases bordered on the criminal. 'Builders were warned more than once that the north-west region of Armenia was prone to earthquakes, but five to nine- storey buildings continued to go up under the slogan "economise",' lamented the Communist Party paper Pravda. 'Take any piece of cement panelling from the side of a building and it's difficult to say whether there's more cement or sand in it.'

However, Mr Gorbachev's dilemma is that, in order to be effective, he must be seen to be in constant control of all the levers of power. Victims of the Armenian quake surrounded him during his visit to demand more cranes and bulldozers, just as unhappy factory workers mobbed him in Siberia this autumn demanding he inter- cede with bureaucrats to get better housing and fill the shops. If he has begun to look like a man holding his country together by sheer willpower, it is no surprise that an edge of intolerance and insecurity is poking through. He dismissed out of hand, for instance, the fears of Armenians that children orphaned by the earthquake would be sent out of the republic where they might be `russified'. He failed to understand, or refused to acknowledge, the sensitivities of a region traumatised by a year of ethnic tensions. More to the point, he failed to see that such fears were a logical result of years of papering over uncomfortable realities.

From the beginning of the crisis, news media and authorities have indulged in soaring flights of rhetoric about the coun- try's restored sense of 'solidarity'. There is a genuinely national feeling of sympathy towards Armenia in its latest hour of trial, but such rhetoric has the taste of official bromides. While Mr Gorbachev is under- standably upset by those whom he sees as trying to make political capital out of a calamity, his own state organs are open to the same charge. The truth is, even in their pain, Armenians cannot forget their recent unhappy experiences with Moscow. Gor- bachev 'didn't bother to come here for nine months', one woman in the devastated town of Spitak told a Western reporter this week. 'What use is there in him coming now?' Armenians are also acutely con- scious of the fact that it is difficult to know who is still missing in the rubble because many of the victims were among the (unregistered) 31,000 refugees from pog- roms in nearby Azerbaijan.

Mr Gorbachev's manner of handling the earthquake crisis provided more evidence of the qualities that have made him indis- pensable to a lowering of superpower tensions. As he likes to repeat, the Soviet Union must learn to live in an interdepen- dent world. But the crisis has also made dear that he is required to become increasingly authoritarian in order to keep his hopes of reform alive. 'It's time we started thinking about becoming super-efficient and mod- ern,' commented Pravda after comparing the professionalism of French rescue work- ers in the quake zone with their slow- moving Soviet counterparts. The tragedy is that it took Mr Gorbachev's sombre jour- ney from New York to Armenia to empha- sise the point.

'I never thought of him getting old.'

Previous page

Previous page