Exhibitions 2

Paul Klee: the Berggruen Klee Collection Cecil Collins (Tate Gallery, till 13 August and 9 July respectively)

Force of gravity

Giles Auty

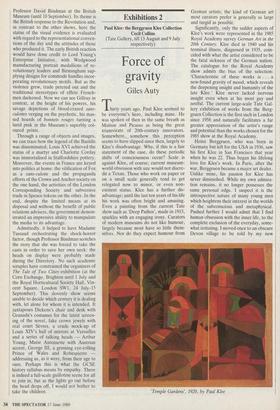

Thirty years ago, Paul Klee seemed to be everyone's hero, including mine. He was spoken of then in the same breath as Matisse and Picasso as being the great triumvirate of 20th-century innovators. Somewhere,, somehow this perception seems to have slipped since then, largely to Klee's disadvantage. Why, if this is a fair statement of the case, do these periodic shifts of consciousness occur? Scale is against Klee, of course; current museum- world obsession with size would not discre- dit a Texan. Those who work on paper or on a small scale generally tend to get relegated now to minor, or even non- existent status. Klee has a further dis- advantage; until the last ten years of his life his work was often bright and amusing. Even a painting from the current Tate show such as 'Deep Pathos', made in 1915, sparkles with an engaging irony. Curators of modern museums do not like humour, largely because most have so little them- selves. Nor do they expect humour from German artists; the kind of German art most curators prefer is generally as large and turgid as possible.

Significantly, only the sadder aspects of Klee's work were represented in the 1985 Royal Academy survey German Art in the 20th Century. Klee died in 1940 and his terminal illness, diagnosed in 1935, coin- cided with what the artist considered to be the fatal sickness of the German nation. The catalogue for the Royal Academy show admits the bias of the selection: 'Characteristic of these works is . . . a new-found gravity of mood, which reveals the deepening insight and humanity of the late Klee.' Klee never lacked nervous insight even when at his most gay and zestful. The current large-scale Tate Gal- lery exhibition of works from the Berg- gruen Collection is the first such in London since 1958 and naturally facilitates a far greater appreciation of the artist's range and potential than the works chosen for the 1985 show at the Royal Academy.

Heinz Berggruen, who was born in Germany but left for the USA in 1936, saw his first Klee in San Francisco that year when he was 22. Thus began his lifelong love for Klee's work. In Paris, after the war, Berggruen became a major art dealer. Unlike mine, his passion for Klee has never diminished. While my own admira- tion remains, it no longer possesses the same personal edge. I suspect it is the introspective nature of many young men which heightens their interest in the worlds of the subconscious and metaphysical. Pushed further I would admit that I find human obsession with the inner life, to the complete exclusion of the everyday, some- what irritating. I moved once to an obscure Devon village to be told by my new 'Temple Gardens', 1920, by Paul Klee neighbour, by way of introduction, that I had a 'luminous green aura' and that my cottage was inhabited already by 'a benign presence' — to go with the smell of chickens previously resident there, perhaps. What I agree, nonetheless, is that Klee's psychic perceptions had a myste- rious force and magic which the pedestrian attempts by most 'otherworldly' artists generally lack entirely.

My personal reservations about the Tate's exhibition of work by Cecil Collins, who died very recently, proceed from the foregoing. Perhaps I entertain less doubts than some about the existence of either inner or after-life; evidence which points in such directions is not so hard to come by. While resident on this planet, however, I am much taken with its appearance, which is more interesting and complex by far than most indifferent attempts by artists to come to terms with it visually might lead one to suppose. Collin's stock subject matter of fools and angels served didactic as well as visual purposes. I doubt whether it is the province of art criticism to argue with either aspect. I am prepared to believe the late artist was a more interest- ing painter and man than many of his contemporaries, but must admit neverthe- less that I find visual interpretations of the paranormal much less interesting than exceptional renderings of our normal world. In short, I see more genuine mys- tery these days in a landscape drawing by Rembrandt than in the whole of surrealism and modern metaphysical painting put together. How our worlds change as we grow older.

Previous page

Previous page