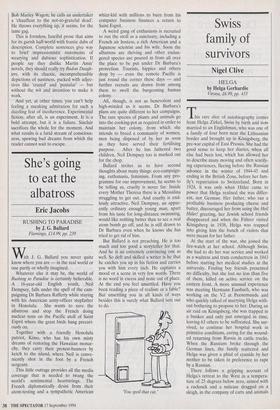

She's going to eat the albatross

Eric Jacobs

RUSHING TO PARADISE by J. G. Ballard Flamingo, £14.99, pp. 239 Wh J. G. Ballard you never quite know where you are — in the real world or one partly or wholly imagined.

Whatever else it may be, the world of Rushing to Paradise is certainly believable. A 16-year-old English youth, Neil Dempsey, falls under the spell of the cam- paigning Dr Barbara Rafferty while staying with his American army-officer stepfather in Honolulu. She wants to save the albatross and stop the French doing nuclear tests on the Pacific atoll of Saint Esprit where the great birds hang precari- ously on.

Together with a friendly Honolulu patriot, Kimo, who has his own misty dreams of restoring the Hawaiian monar- chy, they carry their protest-banners by ketch to the island, where Neil is conve- niently shot in the foot by a French sergeant.

This little outrage provides all the media coverage that is needed to twang the world's sentimental heartstrings. The French diplomatically desist from their atom-testing and a sympathetic American whizz-kid with millions to burn from his computer business finances a return to Saint Esprit.

A weird gang of enthusiasts is recruited to run the atoll as a sanctuary, including a French air hostess, a rich American and a Japanese scientist and his wife. Soon the albatross are thriving and other endan- gered species are poured in from all over the place to be put under Dr Barbara's protection. Tourists, hippies and others drop by — even the remote Pacific is just round the corner these days — and further recruits are drawn from among them to swell the burgeoning human colony.

All, though, is not as benevolent and high-minded as it seems. Dr Barbara's plans are quite different to her campaigns. The rare species of plants and animals go into the cooking-pot as required in order to maintain her colony, from which she intends to breed a community of women, men being disposed of by her as soon as they have served their fertilising purpose. After he has fathered two children, Neil Dempsey too is marked out for the chop.

Ballard invites us to have second thoughts about many things: eco-campaign- ing, euthanasia, feminism. From any pro- gramme for our improvement, he seems to be telling us, cruelty is never far. Inside every Mother Theresa there is a Messalina struggling to get out. And cruelty is end- lessly attractive. Neil Dempsey, an appar- ently ordinary enough young man, apart from his taste for long-distance swimming, would like nothing better than to see a real atom bomb go off, and he is still drawn to Dr Barbara even when he knows she has tried to get rid of him.

But Ballard is not preaching. He is too much and too good a storyteller for that. And he is an extremely convincing one as well. So deft and skilled a writer is he that he catches you up in his fiction and carries you with him every inch. He captures a mood or a scene in very few words. There is no word in excess and none out of place. At the end you feel unsettled. Have you been reading a piece of realism or a fable? But unsettling you in all kinds of ways besides this is surely what Ballard sets out to do.

You spoil that cat.'

Previous page

Previous page