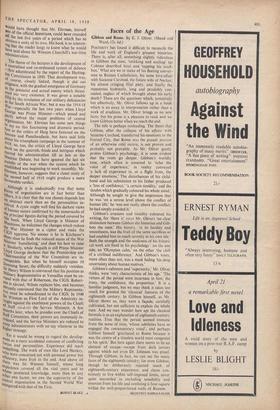

Faces of the Age

Gibbon and Rome. By E. J. Oliver. (Sheed and Ward, 12s. 6d.)

POSTERITY has found it difficult to reconcile the life and work of England's greatest historian. There is, after all, something slightly ridiculous in Gibbon the man, 'smirking and smiling' (as Colman described him) and 'tapping his snuff- box.' What are we to make of his fleeting conver- sion to Roman Catholicism, his tame love-affair with Suzanne Curchod, the future wife of Necker, his almost cringing filial piety, and finally the monstrous hydrocele, long and prudishly con- cealed, neglect of which brought about his early death? These are the questions which, tentatively but effectively, Mr. Oliver follows up in a book which is an essay in interpretation rather than a work of erudition. Mr. Oliver brings us no new facts; but his prose is a pleasure to read, and we know Gibbon better when we reach the end.

The title is perhaps misleading. The thesis that Gibbon, after the collapse of his affaire with Suzanne Curchod, transferred his emotions to the Eternal. City, that Rome was the grande passion of an otherwise cold nature, is not proven and probably not provable. As Mr. Oliver gently probes Gibbon's psychology, it is soon evident that the roots go deeper. Gibbon's worldly tone, • which often is assumed to 'echo the voice of experience,' in reality conveyed 'a lack of experience in, or a flight from, the deeper emotions.' The disturbances of his child- hood and his submission to his father produced a 'loss of confidence,' a certain timidity,' and the 'doubts which gradually coloured his whole mind?, Although he sought to give the impression that he was 'on a serene level above the conflict of human life,' he 'was not really above the conflict; he had simply avoided it.'

Gibbon's evasions and timidity coloured his writing, for 'there is' (says Mr. Oliver) `no clear distinction between Gibbon the historian and Gib- bon the man.' His history, 'in its lucidity and smoothness, was the fruit of the same sacrifices as had enabled him to reach serenity in his own life.' Both the strength and the weakness of his histori- cal work are fixed in his psychology : on the one side, an 'Olympian calm,' on the other 'the chill of a civilised indifference.' And Gibbon's irony, more often than not, was a mask hiding 'his deep uncertainty about human motives.'

Gibbon's calmness and 'superiority,' Mr. Oliver thinks, were 'very characteristic of his age.' The virtues of the period were incarnate in him; the irony, the confidence, the proportion.' It is a familiar judgment, but we may think it takes too much for granted the 'classical' features of the eighteenth century. In Gibbon himself, as Mr. Oliver shows us, they were a facade, carefully cultivated, but not sufficient to explain the whole man. And we may wonder how apt the classical formula is as an explanation of eighteenth-century realities. True that the period seemed immune from the sense of time, 'whose subtleties have so engaged the contemporary mind'; and perhaps Gibbon himself 'gravitated to Rome because it was the centre of a timeless world most congenial to his spirit.' But here again there seems to be an element of escape—escape from dark .terrors against which not even Dr. Johnson was proof. Through Gibbon, in fact, we can see the many faces of the eighteenth century; for even Gibbon, though he deliberately rejected much of eighteenth-century experience, and chose con- sciously to live within self-imposed limits, never quite succeeded in excluding sensibility and emotion from his life and confining it four-square within the well-proportioned walls of Reason.

GEOFFREY BARRACLOUGH

Previous page

Previous page