ARTS

Photography

Innocent pleasures

Tanya Harrod

Faces with Voices: Portraits from an English Community (Gainsborough's House, Sudbury, Suffolk, till 21 June)

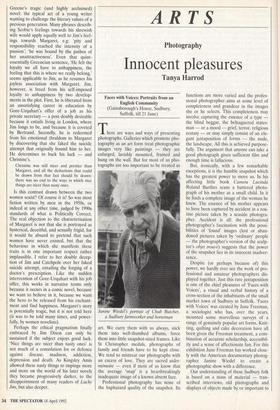

There are ways and ways of presenting photographs. Galleries which promote pho- tography as an art form treat photographic images very like paintings — they are enlarged, lavishly mounted, framed and hung on the wall. But for most of us pho- tographs are too important to be treated as Janine Wiedel's portrait of Chub Butcher, a Sudbury farm worker and horseman art. We carry them with us always, stick them into well-thumbed albums, force them into little snapshot-sized frames. Like St Christopher medals, photographs of family and friends have to be kept close. We tend to mistreat our photographs with an excess of love. They are sacred aides- memoire — even if most of us know that the average 'snap' is a heartbreakingly inadequate image of a known absent face.

Professional photography has none of the haphazard quality of the snapshot. Its functions are more varied and the profes- sional photographer. aims at some level of completeness and grandeur in the images she or he selects. This completeness may involve capturing the essence of a type the blind beggar, the beleaguered states- man — or a mood — grief, terror, religious ecstasy — or may simply consist of an ele- gant juxtaposition of forms — the nude, the landscape. All this is achieved purpose- fully. The argument that anyone can take a good photograph given sufficient film and enough time is fallacious.

But, ironically, with a few remarkable exceptions, it is the humble snapshot which has the greatest power to move us. In his affecting little book Camera Lucinda Roland Barthes scans a battered photo- graph of his mother as a small child. In it he finds a complete image of the woman he knew. The essence of his mother appears to have been captured by accident in a rou- tine picture taken by a seaside photogra- pher. Accident is all: the professional photographer's fascination with the possi- bilities of 'found' images (lost or aban- doned pictures taken by 'ordinary' people — the photographer's version of the sculp- tor's objet trouve) suggests that the power of the snapshot lies in its innocent inadver- tence.

Despite (or perhaps because of) this power, we hardly ever see the work of pro- fessional and amateur photographers dis- played together. Just this rare juxtaposition is one of the chief pleasures of 'Faces with Voices', a visual and verbal history of a cross-section of the inhabitants of the small market town of Sudbury in Suffolk. 'Faces with Voices' was curated by June Freeman, a sociologist who has, over the years, mounted some marvellous surveys of a range of genuinely popular art forms. Knit- ting, quilting and cake decoration have all been given the Freeman treatment, a com- bination of accurate scholarship, accessibil- ity and a sense of affectionate fun. For this exhibition June Freeman has worked close- ly with the American documentary photog- rapher Janine Wiedel to create a photographic show with a difference.

Our understanding of these Sudbury folk is based on a mass of material — tran- scribed interviews, old photographs and displays of objects made by or important to the interviewees. Janine Wiedel's hand- some portraits of the 45 protagonists do not occupy a privileged space. They are simply mounted and unframed and have to fight for our attention as just one part of a composite picture of each individual. The general effect, which could have seemed muddled, is very engaging and Wiedel's pictures stand up to the challenge. There is no need to be a citizen of Sudbury to become simultaneously aesthetically and emotionally involved with these varied images and these people.

The unexpectedly penetrating gaze of a young woman with Down's syndrome is caught by Wiedel and in two further pho- tographs we also see the same young woman with her two sisters — all three in alternately happy and reflective mood. These very fine images by Wiedel are put into context by deckle-edged childhood snaps and by an exquisite little bunch of artificial flowers made by the young woman at the local training centre. Wiedel shows us an attractive middle-aged woman stand- ing in her drawing-room. Photographs of her as a young girl immediately tell us that this delicately pretty room mirrors her his- tory. We instinctively know that this woman has always been loved and cher- ished. A photograph by Wiedel of a woman in her eighties radiates a kind of trusting eagerness, while in an instantly recognis- able snap taken some 50 years earlier her best friend stands beside her. We suddenly notice that they are wearing identical shoes and this curious little detail seems to sym- bolise the loyalty and sweetness of their friendship.

What do we learn about Sudbury? Not that Sudbury is altogether unique, because such an exhibition could have been built round any small town. None the less we get a strong sense of a community with its vari- ous specialised industries, its lively market and its pastoral setting amongst water meadows. The exhibition is weighted in favour of older people and from them above all from the workers on the land we get an idea of service, of the hardness of life between the wars. This sense of duty and of engagement cuts across all classes. There is, perhaps inevitably, a powerful sense of Englishness (but an Englishness which embraces the Indian subcontinent, Tanzania and Trinidad, the birthplaces of four of the protagonists in the exhibition). It is hauntingly present in the accompany- ing book of interviews and it comes through very strongly in all the pho- tographs. Visitors to the exhibition will find their own England in these images.

The world of arts administration in the Eighties has been dominated by talk of community. But it is not easy to use art to reach out and involve the reticent, telly- bound, secular inhabitants of these islands: the best community-arts programmes have worked with immigrant groups whose sense of cultural identity is both beleaguered and strong. But 'Faces with Voices' manages to combine artistic endeavour with a genuine celebration of a community. It also man- ages to convey, without sentimentality, the essential goodness and niceness of people. This is quite an achievement. Twentieth- century art has not tended to celebrate ordinary lives — good news is invariably no news.

Previous page

Previous page