Like a rolling rock

Michael Horovitz

THE DYLAN COMPANION edited by Elizabeth Thomson and David Gutman

Macmillan, £15 .95, pp. 368

The main strengths of this compendium of Dylanology are the accounts by such ebullient writers as Richard Farina, Ken Kesey, Charles Nichol!, Adam Lively, Timothy O'Grady and Geoff Dyer of the sudden excitement when Bob Dylan woke them up, turned them on and changed their lives. Its main drawbacks are that it contains so little by people who have been his companions, and equally little hard analysis. Apart from a few asides by Frank Kermode and Stephen Spender there is virtually no straightforward exposition of the songs. Dylan may have done as much as anyone in the English-speaking world this century to restore poetry to popular songs but none of these essays, reviews, hommages and reminiscences tell the read- er much about how he has done it.

The editors 'hope the Companion goes some way towards rescuing Bob Dylan from the weight of tabloid journalism which has tended to swamp perceptive discussion' — yet they consign 22 pages to the terminally ponderous psychobabble of Michael Ross and Don O'Meara, headed 'Is your love in vain?'. Theirs certainly is. Where Dylan croaks 'Love is all there is/It makes the world go round', they would have us sternly note that . . . The potential for self-actualisation in the private realm of personal relationships is represented in Dylan's songs by the opportu- nities for solitude, for security and a sense of belonging, for stability, acceptance, authen- ticity in relationships, and for affirmation of personal identity through interaction with significant others. In addition, there is the potential to experience human love.

Some of Dylan's later songs can feel quite ordinary or boring, but these chaps should be sent back to the one about 'Don't criticise what you can't understand'.

'Till death do us part, OK?' Thomson and Gutman should for their part Understand that the weight of academic garbage-trucking can swamp the air as thickly as any amount of tabloids.

The almost-as-wordy extrapolations of Christopher Ricks effect a similarly ludic- rous (though intermittently ingenious) translation of some of the lyrics into London Review of Books-speak. This would be plausible if one could imagine Mister Tambourine Man wanting to pitch his minstrelsy at such an effetely intellec- tual readership. If you are more inclined to the view of Bruce Springsteen's Ma who, though `no stiff with rock'n'roll, sat there' when first hearing Dylan on the car radio at her teenage son's request, 'looked at me

and said, "That guy can't sing",' — best forget the whole book.

Springsteen himself, the only singer- musician included, is more persuasive:

Dylan was a revolutionary — he freed your mind the way Elvis freed your body. He had the vision and the talent to make a pop song that contained the whole world. He invented a new way a pop singer could sound, broke through the limitations of what a recording artist could achieve, and changed the face of rock'n'roll. Without Bob the Beatles wouldn't have made Sgt. Pepper, the Beach Boys wouldn't have made Pet Sounds, the Sex Pistols wouldn't have made 'God save the Queen', U2 wouldn't have done 'Pride in the name of love', Marvin Gaye wouldn't have done What's Goin' On?, and there

would never have been a group named the Electric Prunes.

The editors have garnered only a hand- ful of descriptions of Dylan in performance — the most engaging, unfortunately, being a characteristically deadpan one by the DJ John Peel of an apparently less than half-hearted concert at Wembley in 1978:

From the moment the living legend took to the stage it was evident that here was business he wanted accomplished with the minimum of effort. Sounding like one of those talent competition impersonators who have to tell you who they are 'doing', it appeared as much as Dylan could bear to grumble out his lyrics at all. By the time he reached 'The Lonesome death of Hattie Carroll' he was gasping out each word as though playing a dead man trying to com- municate the name of his murderer in an amateur thriller production.

The euphoric 1969 Isle of Wight festival is brought back to life in graphic evocations

by Polly Toynbee and Christopher Logue, but Dylan's spot there is only mentioned in passing. Logue saw 'a good-looking boy in a shiny-white suit singing a Bob Dylan melody a la Sinatra . . . then off. No mes- sage. But a nice smile.' (Memo for the paperback edition — the more so since Thomson-Gutman's Introduction bemoans another publication 'vitiated by perversely lackadaisical proof-reading' — surely that 'melody' should read 'medley'.) Pauline Kael's tart send-up of the myth- making Renaldo and Clara movie is salut- ary, as is Paul Hodson's piece demystifying the conventional macho attitudes millions of enthusiasts for big-time cock rock still seem to find romantic: Men are central to most of Dylan's songs. He reproduces men's privileges over women when he places women as bookends to their journeys or pivots for their interesting rela- tionships. Bob Dylan has not written 'every- body's song'. He rarely sings of women coming, going, initiating, coping, and rarely of men not coping. He rarely sings of women and men as friends.

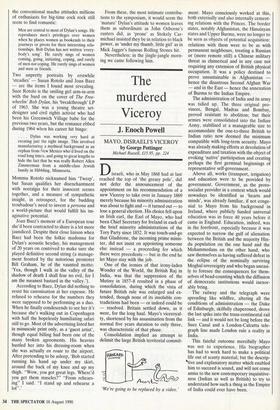

Two unpretty portraits by erstwhile 'steadies' — Susan Rotolo and Joan Baez — are the items I found most revealing. Suze Rotolo is the smiling girl arm-in-arm with the bard on the cover of The Free- wheelin' Bob Dylan, his 'breakthrough' LP of 1963. She was a young theatre set- designer and civil rights activist who had been his Greenwich Village babe for the previous two years, but the romance ebbed during 1964 when his career hit bingo: . . . . Dylan was working very hard at creating just the right image. This involved manufacturing a mythical background as an orphan from New Mexico who'd lived on the road long times, and going to great lengths to hide the fact that he was really Robert Allen Zimmerman from a middle-class Jewish family in Hibbling, Minnesota.

Momma Rotolo nicknamed him 'Twerp', but Susan qualifies her disenchantment with nostalgia for their innocent scenes together, and a measure of sympathetic insight, in retrospect, for the budding troubadour's need to invent a persona and a world-picture that would fulfill his im- aginative potential.

Joan Baez's memoir of a European tour she'd been contracted to share is a lot more jaundiced. Despite their close liaison when Baez had been the folkie madonna for Dylan's acoustic heyday, his management of 20 years on contrived to make sure she played definitive second string (a manage- ment fronted by the notorious promoter Bill Graham, he of the vaunted motto: 'Yea, though I walk in the valley of the shadow of death I shall fear no evil, for I am the meanest bastard in the valley.').

According to Baez, Dylan did nothing to resist his canonisation at her expense. He refused to rehearse for the numbers they were supposed to be performing as a duo. When he finally condescends to see her it's because she's walking out in Copenhagen with half the hopelessly humiliating safari still to go. Most of the advertising listed her in minuscule print only, as a 'guest artist', though equal billing had been one of the many broken agreements. His heavies hustled her into his dressing-room when she was actually en route to the airport. After pretending to be asleep, 'Bob started running his hand up under my skirt, around the back of my knee and up my thigh. "Wow, you got great legs. Where'd you get them muscles?" "From rehears- ing" I said. "I stand up and rehearse a lot".' From these, the most intimate contribu- tions to the symposium, it would seem the 'mature' Dylan's attitude to women leaves them as subordinate as John Osborne's ranters did, as 'prone' as Stokely Car- michael insisted they be in relation to black power, as 'under my thumb, little girl' as in Mick Jagger's famous Rolling Stones hit.

Nevertheless: in the jingle-jangle morn- ing we came following him.

Previous page

Previous page