Crafts

Indonesian Batik (Royal Festival Hall, till 26 August) Flowered Silks: A Noble Manufacture of the 18th Century (V & A, till 28 October) British Studio Pottery (V & A, till 30 September)

Material world

Tanya Harrod

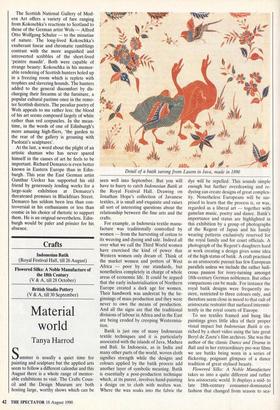

Summer is usually a quiet time for painting and sculpture but the applied arts seem to follow a different calendar and this August there is a whole range of memor- able exhibitions to visit. The Crafts Coun- cil and the Design Museum are both hosting large, worthy shows which can be Detail of a batik sarong from Lasem in Java, made in 1890 seen well into September. But you will have to hurry to catch Indonesian Batik at the Royal Festival Hall. Drawing on Jonathan Hope's collection of Javanese textiles, it is small and exquisite and raises all sort of interesting questions about the relationship between the fine arts and the crafts.

For example, in Indonesia textile manu- facture was traditionally controlled by women — from the harvesting of cotton to its weaving and dyeing and sale. Indeed all over what we call the Third World women have exercised the kind of power that Western women only dream of. Think of the market women and potters of West Africa — poor by our standards, but nonetheless completely in charge of whole areas of economic life. It could be argued that the early industrialisation of Northern Europe created a dark age for women. Their handwork was undercut by the be- ginnings of mass production and they were never to own the means of production. And all the signs are that the traditional divisions of labour in Africa and in the East are being eroded by creeping Westernisa- tion.

Batik is just one of many Indonesian textile techniques and it is particularly associated with the islands of Java, Madura and Bali. In Indonesia, as in India and many other parts of the world, woven cloth signifies strength while the designs and colours applied by the batik process add another layer of symbolic meaning. Batik is essentially a post-production technique which, at its purest, involves hand-painting a design on to cloth with molten wax. Where the wax soaks into the fabric the dye will be repelled. This sounds simple enough but further overdrawing and re- dyeing can create designs of great complex- ity. Nonetheless Europeans will be sur- prised to learn that the process is, or was, regarded as a liberal art — together with gamelan music, poetry and dance. Batik's importance and status are highlighted in this exhibition by a group of photographs of the Regent of Japan and his family wearing patterns exclusively reserved for the royal family and for court officials. A photograph of the Regent's daughters hard at work creating a design gives some idea of the high status of batik. A craft practised as an aristocratic pursuit has few European parallels unless we include the rather ludi- crous passion for ivory-turning amongst 18th-century German noblemen. But other comparisons can be made. For instance the royal batik designs were frequently au- stere, restricted to three colours only, and therefore seem close in mood to that cult of aristocratic restraint that surfaced intermit- tently in the royal courts of Europe.

To see textiles framed and hung like paintings gives little idea of their proper visual impact but Indonesian Batik is en- riched by a short video using the late great Beryl de Zoete's film archives. She was the author of the classic Dance and Drama in Bali and in her extraordinary pre-war films we see batiks being worn in a series of flickering, poignant glimpses of a dance tradition of great stylised beauty.

Flowered Silks: A Noble Manufacture takes us into a quite different and rather less aristocratic world . It displays a mid- to late 18th-century consumer-dominated fashion that changed from season to sea- soh, serviced by a network of designers and weavers in England and France working with skills unmatched by anything we know today. At its height English manufacture centred on the silk-spinning towns of Der- by and Macclesfield and on the Huguenot weavers of Spitalfields. In 1766 the import of French silks was banned and this intro- duced that great period of prosperity com- memorated by some of the more lavish Spitalfied interiors, now, sadly, mostly demolished. In 1824 the import ban was lifted — free trade brought bankruptcies and ruin in its wake.

Unlike the batiks of Indonesia the flo- wered silks of the 18th century appear only to have an iconography of pleasure and beauty. This could of course be a misread- ing. A superficial glance suggests they celebrate wealth and sophistication, a love of the pastoral and an interest in the Orient. But Nathalie Rothstein's forth- coming book Silk Designs of the Eighteenth Century (Thames and Hudson, £55) should elucidate this exhibition and may reveal that these lovely designs have all sorts of unexpected links with high culture.

Finally, British Studio Pottery is de- signed to mark the publication of Oliver Watson's lavish catalogue of the V & A's collection (British Studio Pottery, Phaidon/ Christie's, £75). Culturally studio pottery in perhaps closer to the world of batik than to that of woven silks. It is an anti- industrial art form in origin, aiming to restore a sense of dignity to everyday objects in the 20th century. For that reason it has been unfairly ignored by the fine art world. This small, striking exhibition sug- gests that time will vindicate these lovely objects.

Previous page

Previous page