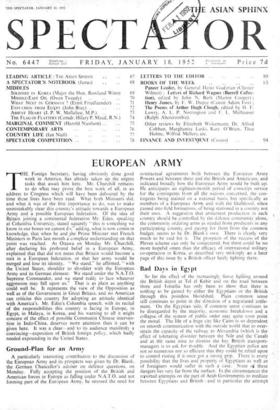

Bad Days in Egypt

So far the effect of the increasingly fierce figliting around the British depot at Tel el Kebir and on the road between there and Ismailia has only been to show that there is nothing to be gained by eitkier the Egyptians or the British through this pointless bloodshed. Plain common sense still continues to point in the direction of a negotiated settle- ment.. On the Egyptian side, if common sense continues to be disregarded by the Majority, economic breakdown and. a collapse of the system of public order may quite soon point the moral. The life of a huge city like Cairo is so dependent on smooth communication with the outside world that to over- strain the capacity of the railway to Alexandria (which is the effect of tolerating disorder between the Nile and the Canal) and at the same time to dismiss the key British transport- managers is to ask for trouble. And the Egyptian police are not so numerous nor so efficient that they could he relied upon to control rioting if it once got a strong grip. There is every possibility that the lives and property of Egyptians as well as of foreigners would suffer in such a case. None of these dangers lies very far from the surface. In he circumstances the reported attempts on the part of Arab GoVernments to mediate between Egyptians and British—and in particular the attempt of General Nun Said, the Prime Minister of Iraq—deserve every encouragement. The suggestion that forces from Arab countries should be included as soon as possible in the Middle East Command is not one that the British Government can afford to reject. In the long run some such solution as this offers the best hope of peace and quiet. Similarly the aim, also attributed to General Nun Said, of securing permanent co-operation between the Arab States and the Western Powers in the defence of the Canal is one which the Egyptian Govern- ment must recognise as reasonable, if it can ever bring itself to calm down again.