POISONOUS AS A RATTLESNAKE

Survivors: A profile of Keith Richards, musical genius of the Rolling Stones

ONCE, when Keith Richards was still resident in London, he ' bought at vast expense an authentic Gestapo staff car. At that time he was unable to drive a manual car, so he took along his valet 'Spanish' Tony Sanchez for instruction. With Bo Diddley's 'The Gunslinger' blaring from the stereo they careered through a number of red lights before crashing into the back of a queue of cars under the Edgware Road flyover. As police sirens began to wail our hero handed the keys to Sanchez. 'Man, I can't handle this,' he said.1 'You take over.' He climbed out and called 'Taxi!'

This early example of escapolpgy may be partly apocryphal, but it tsounOs like our boy. What is certainly true is that of all the ravaged Sixties pop idols, Keith Richards is the luckiest to be alive. Since about 1968, playing guitar for the Rolling Stones has been accompanied by chemical stimula- tion. A human disposal chute for uppers, downers, hash, grass, LSD, cocaine, he- roin and common-or-garden booze, Richards has not been kind to his system. Yet somehow he has survived a ten-year heroin odyssey ,and is now 'clean'. This reflects a certain constitutional toughness, but also an intelligence and good sense he is not often credited with.

Of all the Sixties pop , stars, Keith Richards is probably the most underesti- mated; not only as a junkie who survived his habit, but as the musical genius of the Rolling Stones. To the public he was just the other writing member of the Stones, a retiring vampire figure behind Jagger, the mouth of the group. Jagger was the one who got on the magazine covers, the one with Margaret Trudeau, with Bianca and the jet set, who dined with dukes and achieved respectability. Keith is what he has always been, an amiable layabout.

Yet listen to the distinctive guitar figure which maps out each of the great Rolling Stones songs within two or three bars, before Jagger's voice comes in, listen to `Honky Tonk Women', 'Satisfaction', `Gimme Shelter', 'Soul Survivor' or 'Hand of Fate' and you have a dark, brutal, thrilling sound which is all Keith Richards. Through him comes the link with the black originals, the guitar style of Chuck Berry, Muddy Waters and Bo Diddley. For the Stones were, far more than the Beatles, musical traditionalists. They started as a rhythm and blues band, part of the second wave of affection Britain has felt this century for American negro music — the first being for traditional jazz. And, at first at least, and in the best of their songs, the Stones were interested in an authenticity of 'feel' and rawness of sound by comparison with which modern pop seems tame. Richards's position as the musical leader of the band is not well known. The story is told, in Barbara Charone's admiring biography, of a time when the Stones' manager, Andrew Loog Oldham, was in the process of entering an agreement with the financial wizard Allen Klein. Looking at the Stones Klein asked: 'Which one makes the records?' That one,' said Old- ham, indicating Richards. This is con- firmed by Jagger, who says of their early writing efforts: 'I had a slight talent for wording, and Keith always had a lot of talent for melody from the beginning. Everything, including the riffs, came from Keith.' Jack Nitzsche, who worked with them on their second album, just says:

'Without Keith's rhythm guitar there wouldn't be a Rolling Stones. Keith is the Stones.' Keith came up with a riff he

thought might make an album filler, he gave it the working title 'I Can't Get No Satisfaction'. After Jagger had fleshed it out with words, Richards still thought it too basic for a single.

Richards has never recorded on his own. He was annoyed when Bill Wyman made a solo album in the mid-1970s. He was angry

again this year, for Jagger has made a record on his own for the first time, She's the Bdss, provoking rumours all over again that the Stones might split up. It is a lacklustre catalogue of lyrical cliches and vocal overstatement. For the record Jagger

recruited the best talent money could buy, Jeff Beck, Sly and Robbie, Herbie Han- cock and Bill Laswell, but the result is half-baked, probably because of his super- star listlessness about deciding quite what he was doing.

What the record showed for the first time, as the American critics said, was quite how much Jagger owes to Richards.

Some even said that the only track which was any good was the one Jagger wrote, but did not play, with him. Jagger's words were always mostly inaudible. The secret of the Stones, if there ever was one, was their way of using two guitars, and Richards's habit, often in the descriptive guitar intros, of using a rhythm guitar where one might expect a lead. On Jag- ger's solo effort, Jeff Beck's lighter, more playful tone did not fill the vacuum.

It is possible that Jagger had just become exasperated. The Stones have not been a vital force for many years. After the great

LPs of the late 1960s and early 1970s, Beggar's Banquet, Let It Bleed and Exile on Main Street, they entered a slow decline in which each album has seemed worse than the last. Certainly Some Girls and Tattoo You had fine moments, largely

provided by Keith. And lately Richards has sung one song on his own, 'Before They Make Me Run', apparently a piece of autobiography about his clashes with the police, which sounded wistful and more

human than Jagger. On the latest record, in theory being made now in Paris, Richards will be forced to contribute more ideas than ever, Jagger having written• himself dry.

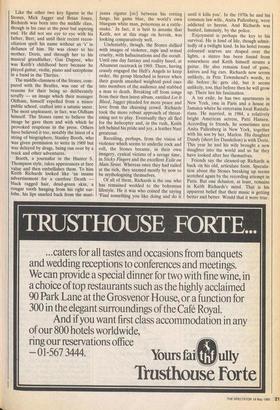

Like the other two key figures in the Stones, Mick Jagger and Brian Jones, Richards was born into the middle class, though in his case at the poor but aspiring end. He did not see eye to eye with his father, Bert, and until their recent recon- ciliation spelt his name without an 's' in defiance of him. He was closer to his mother, Doris, and through her to his musical grandfather, Gus Dupree, who was Keith's childhood hero because he played guitar, violin, piano and saxophone in a band in the Thirties.

The middle-classness of the Stones, com- pared with the Beatles, was one of the reasons for their being so deliberately scruffy — an image which their manager Oldham, himself expelled from a minor public school, crafted into a satanic sneer. The most unpleasant, in fact, was Oldham himself. The Stones came to believe the image he gave them and with which he provoked eruptions in the press. Others have believed it too, notably the latest of a string of biographers, Stanley Booth, who was given permission to write in 1969 but was delayed by drugs, being run over by a truck and other adventures.

Booth, a journalist in the Hunter S.

Thompson style, takes appearances at face value and then embellishes them. To him Keith Richards looked like 'an insane advertisement for a carefree Death black ragged hair, dead-green skin, a cougar tooth hanging from his right ear- lobe, his lips snarled back from the mari- juana cigaret [sic] between his rotting fangs, his gums blue, the world's own bluegum white man, poisonous as a rattle- snake.' In fact, it is best to assume that Keith, not at this stage on heroin, was looking comparatively well.

Undeniably, though, the Stones dallied with images of violence, rape and sexual cruelty, with hallucinations and the occult. Until one day fantasy and reality fused, at Altamont racetrack in 1969. There, having crassly engaged the Hell's Angels to keep order, the group blenched in horror when their guards smashed weighted pool cues into members of the audience and stabbed a man to death. Breaking off from songs from their then latest album, entitled Let It Bleed, Jagger pleaded for more peace and love from the churning crowd. Richards took the more robust approach of threat- ening not to play. Eventually they all fled for the helicopter and, in the rush, Keith left behind his pride and joy, a leather Nazi greatcoat.

Recoiling, perhaps, from the vision of violence which seems to underlie rock and roll, the Stones became, in their own imagery, cynical victims of a savage time, in Sticky Fingers and the excellent Exile on Main Street. Whereas once they had railed at the rich, they seemed mostly by now to be mythologising themselves.

Of all of them, Richards is the one who has remained wedded to the bohemian lifestyle. He it was who coined the saying 'Find something you like doing and do it until it kills you'. In the 1970s he and his common law wife, Anita Pallenberg, were addicted to heroin. And Richards was hunted, famously, by the police.

Enjoyment is perhaps the key to his survival. He is fond of life, though admit- tedly of a twilight kind. In his hotel rooms coloured scarves are draped over the lights, a stereo has been found from somewhere and Keith himself strums a guitar. He also remains fond of guns, knives and big cars. Richards now seems unlikely, in Pete Townshend's words, to die before he gets old, but it seems unlikely, too, that before then he will grow up. There lies his fascination.

A tax exile, he has two apartments in New York, one in Paris and a house in Jamaica where he entertains local Rastafa- rians. He married, in 1984, a relatively bright American actress, Patti Hansen. According to friends, he sometimes sees Anita Pallenberg in New York, together with his son by her, Marlon. His daughter Dandy (short for Dandelion) is with Doris. This year he and his wife brought a new daughter into the world and so far they have looked after her themselves.

Friends say the cleaned-up Richards is back on his old, articulate form. Specula- tion about the Stones breaking up seems scotched again by the recording attempt in Paris. But one delusion, at least, remains in Keith Richards's mind. That is his apparent belief that their music is getting better and better. Would that it were true.

Previous page

Previous page