The laird of Twitts Ghyll

Hugh Cecil

Austen Chamberlain: Gentleman in Politics David Dutton (Ross Anderson £14.95) when shown, as a child, some carica- tures of Joseph Chamberlain and his elder son, Austen, with their monocles, slicked-back hair and buttonholes, I re- member being immediately reminded of the cabaret singing duo, the Western Brothers. Their preposterous smartness struck me as having a certain pathos. I wondered how such a pair of Piccadilly Percys could possibly have got anywhere in high politics. No tears, of course, needed to be shed for Joseph Chamberlain, save in his last years of ruined health. He was one of the toughest politicians of the late Victorian period. His dapper and idiosyn- cratic attire was part of an aggressive, confident flamboyance. I was not wrong, however, in perceiving something poignant about his son, who is the subject of Dr Dutton's thorough and interesting study. By dressing in a fashion identical to that of his powerful father, Austen betrayed a diffident reverence for him which was quite compatible with a high opinion of his own abilities. Joseph groomed him for high office. Austen could only imagine achiev- ing it as a kind of clone of his father. He very nearly did become Prime Minister, and he occupied practically every other eminent ministerial position during his 45 years as an MP from 1892. He did so, however, with little of the distinction which his background and courteous, dignified manner might have led people to expect. Arthur Balfour, discussing with Stanley Baldwin Austen's failure to reach the highest pinnacle, offered an explanation which it is hard not to endorse after reading this book: 'Don't you think it is because he is a bore?'

A kindly, honourable man, Austen also was solemn, stiff and pompous and without creative flair. His utterances were un- failingly commonplace: he talked of dead horses being flogged, of lions' tails being twisted and of himself being 'mightily troubled'. He lacked qualities esential in a leader — tenacity, aggression and capacity for sustained hard work — all of which 'Great Joe' had possessed. Nor had he his father's power to inspire. Curiously, however, despite his mildness and recti- tude, he was almost as often the object of political attack. In one respect his mental- ity resembled Joseph's — neither was able to look at problems from a wide angle of vision; but where Joseph's single-track mind dwelt on one grandiose radical scheme after another to reform society and Empire, Austen only really wished to conserve, to defend and to keep the peace, if that were possible. When he thought hard about a subject, his views were often sensible. However, even during the long period from 1906 to 1914 when Joseph was stricken and in a wheelchair, it was im- possible for Austen to take an independent line.

He battled conscientiously for his father's policy of tariff reform. Nonethe- less, he disappointed parental expecta- tions: a terror of appearing too `pushfur — Joe Chamberlain's nickname in earlier years — made Austen, in 1911, muddle his chances of securing the party leadership, which passed to Bonar Law. Afterwards, he resented Law's success, and this per- manently damaged their relations. The same touchiness and the same self- destructive hesitancy on the brink of triumph characterised the rest of his career. After Bonar Law resigned in

March 1920 from the leadership, Chamber- lain took over without serious opposition. However, after the Lloyd George Coali- tion broke up in 1922, he was ousted by a Conservative party avid to stand on its own and escape the moral contamination of Lloyd George, whom he continued loyally to support. It is hard not to sympathise with Chamberlain on this occasion. The spectacle of the diseased Bonar Law lead- ing the attack was unedifying: he display- ed, as Winston Churchill recalled, 'person- al ambition not hampered by chivalry and only partially hampered by scruple'. The result was that Law, rather than Austen, became shortly afterwards the next Con- servative Prime Minister. Pride prevented Chamberlain from making his peace with his rival, and he had not been given a cabinet post by May 1923 when the new Prime Minister became too ill to continue. Consequently, there was no question of his being considered as Law's successor, and instead Stanley Baldwin was chosen. Au- sten disdained to ask Baldwin for office, but was wounded when he was offered nothing of sufficient importance. Recon- ciled with Baldwin superficially through Neville Chamberlain, after the Conserva- tive government had lost power, he found a place in the shadow cabinet, though he grumbled about his new leader, whom he despised as talentless and inexperienced.

As Conservative Foreign Secretary from 1924 to 1929, he enjoyed his greatest period of prestige. He was inordinately Pleased with his part in the conclusion of the Locarno Treaties which, it was ex- pected, would end the resentments in Europe caused by the Versailles settlement and form the basis of a permanent peace. He received the Nobel Peace Prize and the Garter for his efforts, but Locarno, in fact, settled little and had no lasting results; nor Was Austen's diplomacy nearly as signifi-

cant as the work of the German statesman Stresemann at the conference. He never seems to have been disabused of his achievement and basked in its illusory radiance throughout the disappointing Years that followed.

When Baldwin, whose leadership of the Party he openly criticised in 1931, joined a National government a few months later, Austen was passed over for the post of Foreign Secretary in favour of an even older man, Lord Reading. Among his family, he could not conceal his disappoint- ment. Neville Chamberlain recorded:

A. had worked himself into a very emotional condition and burst out that he was humili- ated and treated as a back number. His lips trembled and tears came into his eyes and altogether he made us all very unhappy and uncomfortable.

The last period of his political life, though spent on the back benches, was, strangely, his most admirable. To his eter- nal credit, he denounced Hitler and the Nazi regime publicly and uncompromising-

1Y; had he lived longer — he died in March 1937 — he would certainly have been in violent conflict with his brother Neville over foreign policy. One could have wished for more details of Austen's private life in Dr Dutton's book — on his finances, his complex relationship with Neville and the charac- ters of his sisters, Ida and Hilda, with whom he constantly corresponded. This sort of information is a particular strength of David Dilks' recent biography of Neville Chamberlain. But Dr Dutton's dispassion- ate observations about Austen's personal- ity are penetrating and well illustrated. The

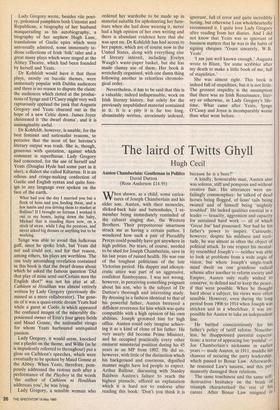

photographs that accompany the text are eloquent; best of all is the picture of his subject 'Relaxing at his country home, Twitts Ghyll'. It shows 'the desiccated patriarch' perched uneasily on a small stool in a narrow space between a pile of logs and the fireplace. The expression on his face suggests that he has just read of his exclusion from office in the evening paper and is wondering whether self-immolation is the best way of upsetting Baldwin.

Previous page

Previous page