The raised eyebrow

Patrick Skene Catling

The Collected Short Stories of Noel Coward Volume II Introduction by Martin Turner (Methuen £9.95) LIke large, very dry martinis with a zest of lemon, the works of Sir Noel Peirce Coward (1899-1973) can subdue that bor- ing old nag, the aesthetic superego, and make one laugh and weep incontinently at the small jokes and sadnesses of life and death. He had a genius, which he manipu- lated with great skill, to make sentimental- ity seem elegant and mock elegance seem genuinely sentimental.

Some critics evidently believe, or believe they should seem to believe, they would be shirking the professional responsibility of

their solemn calling if they acknowledged publicly that they occasionally experience the emotions which ordinary people feel when a work of art, even an easily compre- hensible one, reminds them of their com- mon humanity. Pop art should not be condemned merely because it is popular. There is admirable pop, as well as con- temptible pop; and certainly there are many valid occasions for simple divertise- ment. Where is it written in letters of holy fire that the ironing-board of the bed- sitting room is more significant than the drawing-room baby grand piano? Meaningful relationships can be conducted in silk dressing-gowns; soiled jockey-shorts are not de rigueur.

Even so, John Osborne shattered the icons of London theatrical orthodoxy, as well as radically altering the style of dress, in 1956, when Look Back in Anger opened at the Royal Court, just as Noel Coward himself had startled the West End in 1924 with his own avant-garde success, The Vortex. In each of those years, the fashion- able suddenly became old-fashioned. Osborne's play opened only 13 days after Coward's South Sea Bubble, not one of his best productions, and made it seem even flimsier and emptier than it actually was. After three decades of being regarded as super-sophisticated and daringly witty. Coward to some critical analysts, seemed — horror of horrors! — dull. Rather tatty. Mayfair.

Naturally, he was painfully wounded: there is nobody thinner-skinned than a self-made aristocrat. It must have been absolutely sick-making for poor Noel to be jeered at, and then ignored, by clever, young pseudo-proles.

But behind Coward's public mask of romantic comedy there was another mask, made of steel mesh, vulcanised rubber and asbestos; and behind that there was an honestly self-regarding realist with a talent to survive. The middle-aged trouper was far from finished. His own determination alone would have kept him going profes- sionally; and, of course, he was encour- aged by a large number of loyal fans of his own age and epoch. They shared his demonstrative proud fondness for London and Englishry, the haut-bourgeois glamour of the Lyons tea-tent in the garden of Buckingham Palace, and gallant reckless- ness aboard Royal Navy destroyers. His supporters applauded him as long as they lived, many of them until his apotheosis, which occurred when the Queen Mother memorialised him in Westminster Abbey. Some of them and their descendants still applaud his works.

Theatre- and cinema-goers, televiewers and listeners to radio all over the world continually rediscover his plays, such as Blithe Spirit, which he wrote in six days in 1941. There must always be musicians somewhere rendering his songs, such as `I'll See You Again,' his biggest and most durable hit, which he wrote for Bitter Sweet in 1929.

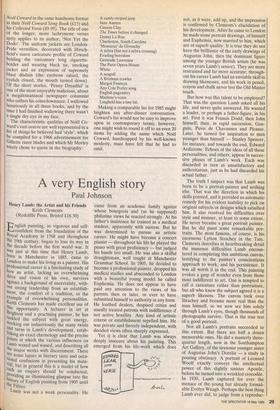

According to Sheridan Morley, whose excellent, affectionately resuscitative biography, A Talent to Amuse, was pub- lished first in 1969, soon after The Master's reputation seemed critically moribund, and was recently republished, with a new pro- logue and epilogue (Pavilion/Michael Joseph £12.95), Coward 'left behind him over fifty plays, twenty-five films, hun- dreds of songs, a ballet, two autobiog- raphies, a wartime diary, a novel, several volumes of short stories and countless poems, sketches, recordings and paint- ings . . Methuen should be thanked warmly for just having published the second and final volume of The Collected Short Stories of Noel Coward in the same handsome format as their Noel Coward Song Book (£15) and his Collected Verse (0.95). The title of one of the longer, more lachrymose verses aptly applies to its author, 'Not Yet the Dodo'. The uniform jackets are London- Pride vermilion, decorated with Hirsch- field's suave caricature profile of Coward holding the customary long cigarette- holder and wearing black tie, smoking jacket and an expression of supremely blasé disdain (the eyebrow raised, the eyelids closed, the mouth turned down). Of the short stories, 'Penny Dreadful' is one of the most enjoyably malicious, about a megalomaniacal newspaper columnist, Who suffers his comedownance. I wallowed luxuriously in all three books, and by the time I had finished wallowing there wasn't a single dry eye in my face.

The characteristic qualities of Noel Co- ward's vast oeuvre are well represented in a list of things he believed had 'style', which he compiled for a 1966 advertisement for Gillette razor blades and which Mr Morley wisely chose to quote in the biography: A candy-striped jeep

Jane Austen Cassius Clay

The Times before it changed

Danny La Rue Charleston, South Carolina 'Monsieur' de Givenchy

A zebra (but not a zebra crossing)

Evading boredom Gertrude Lawrence The Paris Opera House White A seagull A Brixham trawler Margot Fonteyn Any Cole Porter song English pageantry Marlene's voice Lingfield has a tiny bit.

Making a comparable list for 1985 might brighten any after-dinner conversation.

Coward's list would not be easy to improve upon in contemporary terms; however, one might wish to round it off to an even 20 items by adding the name which Noel Coward, handicapped by his well-known modesty, must have felt that he had to omit.

Previous page

Previous page