Court jester, caught out

Frances Spalding

NINA HAMNETT: QUEEN OF BOHEMIA by Denise Hooker

Constable, £15

01=11■- When Nina Hamnett died the Times, in a lengthy obituary, declared that howev- er much she had sacrificed her art to the Bohemian in her, as a person she was a Complete success. Her alcoholism, belliger- ence and compromising penury were Politely overlooked. But the fact that she did survive the transition from serious artist to celebrated personality, becoming Queen of Fitzrovia and its alcoholic haunts, is proved by this unsparing but affectionate biography. What aided her survival was her torso.

She was 16 when she first recognised this advantage. Taught by her grandmother to dress and undress under her nightdress, she one day removed all her clothes, stood in front of the mirror and discovered she was far superior to the naked models she drew at art school. Seven years later she posed to Gaudier-Brzeska. He executed three torsoes, one in clay, making from this two plaster casts, one with a damaged left breast. 'You know me m'dear,' Nina intro- duced herself to Ruthven Todd, 'I'm in the V & A with me left tit knocked off.' The joke never palled. 'Don't forget I'm a museum piece darling,' she warned an American GI, half her age and about to enter her bed. She titled her autobiography Laughing Torso and in her cups followed the boast that Modigliani had declared her breasts the best in Europe by pulling up her sweater to prove it. She approached 60 with confidence undimmed: 'Here's the old torso, how does it look?'

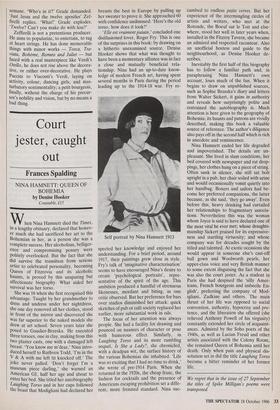

'Elle est vraiment putain,' concluded one disillusioned lover, Roger Fry. This is one of the surprises in this book: by drawing on a hitherto unexamined source, Denise Hooker shows that what was thought to have been a momentary alliance was in fact a close and mutually beneficial rela- tionship. Nina had an up-to-date know- ledge of modern French art, having spent several months in Paris during the period leading up to the 1914-18 war. Fry re- Self portrait by Nina Hamnett 1913 spected her knowledge and enjoyed her understanding. For a brief period, around 1917, their paintings grew close in style. Fry's talk of 'imaginative characterisation' seems to have encouraged Nina's desire to create 'psychological portraits', repre- sentative of the spirit of the age. This ambition produced a handful of strenuous likenesses, mordant and biting, as one critic observed. But her preference for bars over studios diminished her attack: quick sketches of pub or cafe society replaced her earlier, more substantial work in oils.

The focus of her attention was always people. She had a facility for drawing and pounced on nuances of character or pose with humorous effect. Similarly, in Laughing Torso and its more rambling sequel, Is She a Lady?, she chronicled, with a deadpan wit, the surface history of the various Bohemias she inhabited. 'Life was so exciting that I had no time to drink,' she wrote of pre-1914 Paris. When she returned in the 1920s, the cheap franc, the fashion for cocktails and the presence of Americans escaping prohibition set a diffe- rent, more frenzied standard. Nina suc- cumbed to endless petits verres. But her experience of the intermingling circles of artists and writers, who met at the Rotonde, the Boeuf sur le Toit and else- where, stood her well in later years when, installed in the Fitzroy Tavern, she became an admired and respected raconteur. Also an unofficial hostess and guide to the neighbourhood, as Denise Hooker de- scribes.

Inevitably the first half of this biography has to follow a familiar path and, in paraphrasing Nina Hamnett's own account, loses much of the fun. When it begins to draw on unpublished sources, such as Sophie Brzeska's diary and letters from Walter Sickert, it gains in authority and reveals how surprisingly polite and restrained the autobiography is. Much attention is here given to the geography of Bohemia; its haunts and patrons are vividly described, making this book a valuable source of reference. The author's diligence also pays off in the second half which is rich in anecdote and reminscence.

Nina Hamnett ended her life degraded and impoverished. The details are un- pleasant. She lived in slum conditions, her bed covered with newspaper and rat drop- pings, her clothes hung on a piece of string. Often sunk in silence, she still sat bolt upright in a pub, her chair soiled with urine and would occassionally vomit quietly into her handbag. Boxers and sailors had be- come her preferred companions, the latter because, as she said, 'they go away'. Even before this, heavy drinking had curtailed her relationships to fragmentary associa- tions. Nevertheless this was the woman whom Joyce is said to have declared one of the most vital he ever met; whose draughts- manship Sickert praised for its expressive- ness and startling virtuosity; arid whose company was for decades sought by the titled and talented. At exotic occasions she would appear in someone else's cast-off ball gown and Woolworth pearls, her upper-class voice and very British manner to some extent disguising the fact that she was also the court jester. As a student in Paris she had despised the 'silly Amer- icans, French bourgeois and imbecile En- glish', preferring the company of Mod- igliani, Zadkine and others. The main thrust of her life was opposed to social convention, authority, hypocrisy and pre- tence, and the liberation she offered (she relieved Anthony Powell of his virginity) constantly extended her circle of acquaint- ances. Admired by the Soho poets of the 1940s, as well as Lucian Freud and other artists associated with the Colony Room, she remained Queen of Bohemia until her death. Only when pain and physical dis- solution set in did the title Laughing Torso become a bitter reminder of her former life.

Previous page

Previous page