SIMPSON'S

IN-THE-STRAND

SIMPSON'S

IN-THE-STRAND

CHESS

Mind-bending

Raymond Keene

CHESS is more than pure calculation. It also involves qualities of imagination, cre- ative leaps and the ability to detect out- wardly paradoxical fluctuations in the rela- tive values of material, space, tempo and structure. Were it not for these factors, Garry Kasparov would stand little chance in his upcoming match against IBM's Mark II Deep Blue computer which starts in New York early next month.

The machine can now analyse 1,000 mil- lion different positions each second, never tires and is not liable to fall victim to the psychological terror tactics which Kasparov regularly deploys against human oppo- nents. It is not that Kasparov behaves unsportingly in human v. human competi- tions, rather that a large concentration of his forces around an opponent's king may legitimately cause the other side to panic. Computers do not panic. If Kasparov's attacks are not objectively sound, they will not break through against Deep Blue.

When Kasparov faced the silicon mon- ster a year ago in their first six-game clash, I forecast a 4-2 outcome in his favour. In spite of a sensational loss by Kasparov in game one, my prognostication turned out to be accurate. I also stand by this score for the coming clash. The machine has been upgraded but Kasparov himself gained valuable insights in last year's battle into the way computers 'think'. By and large, superb though they may be at calculating tactics, they are deficient in long-range strategic planning.

Here is the decisive game from last year's match, one in which Kasparov exploited his superior strategic abilities to force an overwhelming victory. Garry Kasparov—Deep Blue: Philadelphia 1996; Queen's Pawn Opening.

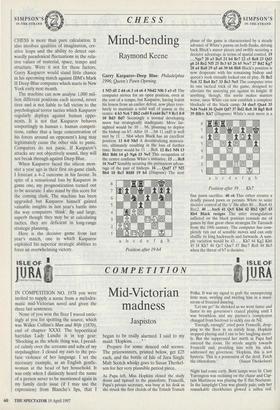

1 NS d5 2 d4 c6 3 c4 e6 4 Nbd2 Nf6 5 e3 c5 The computer strives for an open position, even at the cost of a tempo, but Kasparov, having learnt his lesson from an earlier defeat, now plays reso- lutely to maintain a solid wall of pawns in the centre. 6 b3 Nc6 7 Bb2 cxd4 8 exd4 Bel 9 Rcl 0-0 10 Bd3 Bd7 Seemingly a normal developing move but strategically inadequate. More far- sighted would be 10 ... b6, planning to deploy the bishop on b7. After 10 ... b6 11 cxd5 is well met by 11 Nb4 when Black has an excellent position. 11 0-0 Nh5 A decentralising manoeu- vre, ultimately resulting in the loss of further time. Better would be 11 ... Rc8. 12 Rel Nf4 13 Bbl Bd6 14 g3 Ng6 15 Ne5 This occupation of the centre confirms White's initiative. 15 ...Rc8 16 Nxd7 Sensibly securing the permanent advan- tage of the pair of bishops. 16 ... Qxd7 17 Nf3 Bb4 18 Re3 Rfd8 19 h4 (Diagram) The next

phase of the game is characterised by a steady advance of White's pawns on both flanks, driving back Black's minor pieces and swiftly securing a decisive advantage in terms of spatial control. 19

Nge7 20 a3 Ba5 21 b4 Bc7 22 c5 Re8 23 Qd3 g6 24 Re2 Nf5 25 Bc3 h5 26 b5 Nce7 27 Bd2 Kg7 28 a4 Ra8 29 a5 a6 30 b6 Bb8 Black's position is now desperate with his remaining bishop and queen's rook virtually locked out of play. 31 Bc2 Nc6 32 Ba4 Re7 33 Bc3 Ne5 The computer tries its one tactical trick of the game, designed to alleviate the annoying pin against its knight. If anything, though, this sortie makes matters worse, since White can now establish a complete blockade of the black camp. 34 dxe5 Qxa4 35 Nd4 Nxd4 36 Qxd4 Qd7 37 Bd2 Re8 38 Bg5 Rc8 39 Bf6+ Kh7 (Diagram) White's next move is a

fine pawn sacrifice. 40 c6 This either creates a deadly passed pawn or permits White to seize decisive control of the 'c' file after 40 ... Rxc6 41 Rec2. 40 ... bxc6 41 Qc5 Kh6 42 Rb2 Qb7 43 Rb4 Black resigns The utter strangulation inflicted on the black position reminds me of games by that great chess strategist Dr Tarrasch from the 19th century. The computer has com- pletely run out of sensible moves and can only shuffle its king backwards and forwards. A sam- ple variation would be 43 ... Kh7 44 Kg2 Kh6 45 f4 Kh7 46 Qe7 Qxe7 47 Bxe7 Re8 48 Bc5 when the threat of b7 is decisive.

Previous page

Previous page