Exhibitions 1

A Noble Art (Department of Prints and Drawings, British Museum, till 24 September)

Masters and muses

Felicity Owen

0 ur most venerable institution is to be commended for an exhibition that in giving scholarship full rein exposes the triviality of pick 'n' mix and other passing trends. With admirable disregard for political correct- ness, in Amateur Artists and Drawing Mas- ters c 1600-1800 Dr Kim Sloan reconstructs the development of an artistically backward nation, underlining the contribution of `princes or rather those with princely minds', the virtuosi. These gentlemen scholars were amateurs in the best sense of the word, contributing skills and learning, the pursuit bringing them relief from the acute boredom and melancholy so pervasive in polite circles enduring a northern climate.

By the middle of the 17th century the influence of the cosmopolitan but sadly short-lived court of the greatest collector, Charles 1, had transformed expectations. Whereas home-grown art was still mainly limning (painting in miniature), travellers discovered a desire to record views: the gifted John Evelyn sketched between Rome and Naples in 1645 for a series of etchings; while the King's nephew, the charismatic Prince Rupert, was more inter- ested in scientific experiments. He returned to England after the Restoration with the secret of mezzotinting and his 1662 portrait of 'The Little Executioner' sparkles.

Certain of the moral superiority of fellow members, the Prince and Evelyn kept this knowledge within the newly founded Royal Society, thereby leaving English print mak- ers, 'mere Meckanicks', to continue for sev- eral decades with the old processes used by Wencelas Hollar, whom the Earl of Arun- del had brought to London in 1636. His fine drawings and those of his friend, the York virtuoso Francis Place, heralded a new interest in landskip' taken from nature or imagination, which became the English pursuit in the next century. One of the first to use watercolour washes freely, the amateur William Taverner, was prone to people his vernal scenes with strangely wooden nymphs — little wonder that 'this noble and ingenious art' was deemed `innocent'.

By now thought effeminate, limning was allowed to the opposite sex: Lady Carnar- von's flowerpiece of 1662 is remarkable and Samuel Pepys, following in the foot- steps of his betters, risked introducing the good-looking drawing master Alexander Browne to his wife, hopeful that her pro- ductions would bring him credit.

At court the interest in art was revived by George III whose poor trapped daughters, well taught by a succession of masters, mostly foreign, produced pleasant portrait and flower sketches, but none so stunning as the collages of their prolific old friend, Mrs Mary Delany. The King himself had been grateful in his frustrated early years for the diversion into every aspect of draw- ing, from perspective and fortifications to architecture (the view of Syon House is very assured), and his regard for artists led to his vital role in the Royal Academy's foundation in 1768.

That year, a founder member, Paul Sandby, was promoted chief drawing mas- ter at Woolwich, the leading military academy, and his topographical water- colours set a standard not only for officers and aristocratic families but also amateurs with antiquarian interests such as Francis Grose, who published prospects taken on his tours. A more aesthetic approach was encouraged by the inventive Alexander Cozens who for a time taught Etonians the value of an 'accidental blot'; and, equally influential, the Revd William Gilpin, who developed the theory of picturesque land- scape, thereby attracting a stream of lady admirers relieved to forego accuracy for an ideal composition.

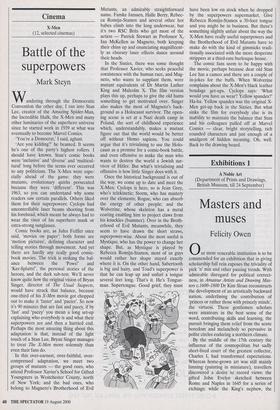

Even Charles Fox was amused to join the debate about the definition of beauty and the picturesque, while the leading amateur painter and lifelong patron Sir George Beaumont used his parliamentary years, the 1790s, to talk up the British artist. Essentially an 18th-century figure, he was happiest sketching in pencil and grey wash alongside his professional friends, but would later condemn the increased use of watercolours resulting from the discovery of new but often transitory pigments. The amateur Edward Swinburne's brilliant azure in his Tasso's House, Sorrento' (1797) on the cover of the excellent cata- logue is a rare unfaded example.

Only rigorous selection has kept this enjoyable exhibition down to 200 exhibits, mainly from the BM's enormous holdings, but with loans mostly from the Royal Col- lection. One regret is the omission of satiri- cal drawings in which the Georgians excelled: a few by Henry Bunbury and John Nixon would have leavened the loaf.

Detail from Tasso's house, Sorrento' (1797), by Edward Swinburne

Previous page

Previous page