Is it the law's business?

Robert Lindsay

The Bill to amend the law on abortion will receive its second reading on February 22. Here, Robert Lindsay, a barrister and freelance writer on legal and social issues, discusses the legal, jurisprudential and social implications of the law.

"Goodbye baby and amen," wrote Peter Evans' affectionately signalling the departure of the exhilarating and dazzling 'sixties. It was a revolutionary era, not least ot all on the legislative front. Legislation reflected changes in social attitudes towards suicide, homosexuality, capital punishment, race relations, divorce and abortion. Most of these, perhaps all, have met with approbation, albeit retrospectively, but the spectre of the unborn child haunts some who wonder if the 'seventies will , carry a slogan, "Goodbye Granddad and amen." The battle for easier abortion has been won, the dust and agitation has settled, the Lane Commission, hitherto lonely figures threading a sedate path through the carnage, have now measured the value of the victors' gain, numbered the casualties, and calculated the excesses of the plunderers who declaim happily the reality of 'abortion on demand.' The bystanders can now reflect on the validity of the ethical strategy deployed and consider its relevance in the impending struggle for further reform.

Three distinct questions arise: Is abortion wrong? Is it the law's business? Is the scope of legal involvement effective at present?

The Christian churches believe that abordon in principle is wrong because they say human life is derived from God and therefore sacred. The Lord says to Jeremiah, "Before I formed you in the womb I knew you for my own" (Jeremiah 5:1). The Protestant theologian, Bonhoeffer, thinks the issue is confused by attempts to define a human being, since "God certainly intended to create a human being and that this nascent human being has been deliberately deprived of his life." However, for the humanist, who denies the divinity, this is an inadequate assertion. He will recognise only the right to life of a human being of the same distinctive nature as himself. It is upon the foetus's individual humanity that the issue pivots.

Four inferential aids may be used to identify the embryo's status.' Is the foetus alive? The chromosomes of a new being have formed "a master plan for growth"' once the male sperm and female ovum have fused. After six days the embryo will have implanted in the uterine wall and is unquestionably alive. Is the foetus individual? The fusion introduces "an entirely new genetic package:" after seven weeks the heart is beating, the brain is receiving and emitting neurohormonal signals, and the sex of the foetus can be verified. At twelve weeks the foetus is drinking the amniotic fluids in the womb (it is between the tenth and twelfth week that most abortions take place). At this stage the foetus is not independent but is apparently individual. _

Is, therefore, the foetus human? Naturally, this is a question of definition but the concept of human life in evolvement is one which the humanist can perhaps accept without reserve. "The infant develops into a child, the child into the adult and even the adult continues to modify his form and function into old age and death."6 It would seem that any demarcation after conception is too arbitrary. Is the foetus a person? Personhood suggests social interaction: "I'm a real live person," the disc jockey's dummy shouts from the transistor. Lionel Trilling, the American critic, might even agree with him: it seems existence and personhood depend upon other people's recognition. The argument has come full circle: the unwanted child is being refused recognition. It is possible to agree with Pius XII "the inviolability of the life of an innocent human being does not depend on its greater or lesser value."'

Many would agree, however, that, while human life in its embryonic form merits regard, abortion may have in specific cases a moral respectability to which we must reluctantly sacrifice moral honesty. But we cannot justify the foetus's epitaph being inscribed with the euphemistic words 'situational ethics.' The claim is that moral decisions should not be based on universal moral laws but should instead be derived from the situation in which the individual finds herself. As Dr Fletcher puts it: "No act . . . is intrinsically

good or evil. The morality of any act depends on (the circumstances and the motives)."9 This is open to criticism on two grounds. First, situational ethics postulates the absence of moral absolutes yet one is being used as the criterion by which the morality of actions is to be judged. Secondly, as Russel Shaw" points out, the mother is expected to make a choice with a degree of disinterested concern which few, if any, can possess.

It follows that if we are pursuaded that abortion, in principle, is prima facie reprehensible we can consider the second question. Is abortion the law's business? Should some restraint on abortion be enshrined in the criminal law? Should there be even theoretical limits as set out in the 1967 Act?

Laws appear to have an effect in determining the tone of community response. Within ten years of introduction of liberal legislation in Japan abortions were running at over a million a year. The converse, that Christian morality has influenced the law, is equallY, true; but secular law is not an expression 0,1 the divine or 'natural' law. "A state whicn, refuses to enforce Christian beliefs" says Lora Devlin "has lost the right to enforce Christian morals."" So, with a sonorous valediction, VI° outstanding jurists joined issue on the proPer function of the criminal law. Their text Wa,..5 the Wolfenden Committee report" whio; successfully recommended that homosexua' behaviour between consenting adults in private should not be a criminal offence. Thei. report stated: "there must remain a realm 19' private morality and immorality which is, T, brief and crude terms, not the law's business. Professor Hart denies that the enforcement of morals is any concern of either the legislative or the judges:4 He endorses die utililitarian view propounded by John Stuart Mill: "The only purpose for which power can rightfully be exercised over any member of a civilised community against his will is prevent harm to others." Mill then went on elaborate his definition: "His own good, eitbe' physical or moral, is not a sufficient warrant, He cannot rightfully be compelled to do v. forbear because it will be better for hint to d° so, because it will make him happier, because in the opinion of others to do so would be wise or even right." The doctrine is not t° apply to children or backward societies' Professor Hart gives only qualified support t° the second part of Mill's definition believing that a limited paternalism (i.e. "the protectiOn of people against themselves') is permissible' Hart goes on to justify this departure fronio MTh "choices may be made or consent give,/ without adequate reflection or appreciation the consequences; or in pursuit of mere4s transitory desires; or in various predicafre"--,t when the judgement is likely to be clouded; under inner psychological compulsion."11 One might be excused thinking Profess' Hart is here concerned with the vacillatill mother who is considering an abortion. Infit',5 he is reconciling his modified version of Millr, doctrine with: the law's refusal either to Pell mit the uncontrolled distribution of certa!0 drugs; or to recognise consent as a defence Lis murder or assault. Of course Hart, like Willer concerned with what the law should be ratlike than what it is; but the former holder of t"„t Oxford Chair in jurisprudence does not obj% to legal intervention in the three situatle cited, though he does appear to think ,,„t, theoretical limits, imposed by the 1967

too restrictive." ted

It follows that those who favour a restr-c abortion law can legitimately appropriate tills theory of law as proclaimed by Mill and the celebrated apostle. They are not forced, as ifl. open abortionists proclaim, to enlist the ,0 vidious principle of moral dogma or taboo.,_ 'a justify legal enforcement. The foetus Iv separate human entity and therefore earns by protection of Mill's definition (approvediv Hart) as an individual whose physica.1 tegrity can be respected. Alternatively, If 11

Physical integrity is denied, Professor Hart's modified thesis sanctions his immunity (though he himself might not approve it), since a woman's ill-considered consent comes Within the ambit of paternalism. Mill would not tolerate such a concession; but even he is compelled to acquiesce in any veto which the law sees fit to extend to an adolescent mother. Lord Devlin proposes an alternative doctrine to that of Mill which many regard as the Prevailing attitude of the English judiciary. His concept of criminal law is derived from two related beliefs: the Platonic ideal that society exists for the promotion of virtue among its citizens; and that society, which is defined as a community of "cohesive sen

thnent,"19 may legislate to preserve the com

munity belief that forms its definition and essence. He places no theoretical limits on the enforcement of morality by the state but the Immorality warranting punishment must be such as to cause a reasonable man to feel

Intolerance, indignation and disgust;"20 his

disapproval is not sufficient warrant. This common morality is "a blend of custom and

conviction of reason and feeling of experience Slid prejudice;"21 the sentiments so expressed may be derived from Christian teaching but their authority lies not in their provenance but in their popularity.

The theory of Lord Devlin was expounded °etore the 1967 reform of the Abortion Law. At that time the only defence open to the abortionist was a bona fide belief that abor

tion was necessary to preserve the life of the Mother. Life was generously interpreted as LInPairment to physical or mental health, be

',1g an undefined distance short of instanreous death. Applying the operative law to

'as concept of the criminal law's function,

Lord Devlin said "the community as a whole Is not deeply imbued with a sense of sin: the al.v sags under a weight which it is not constructed to bear and may become permanently Warped. "' Later, he concludes: "If the law on abortion causes unnecessary misery, let it be atnended, not abolished on the ground that abortion is not the law's business."

, What then is the effective scope of the law's tovolvement? By 1967 the pressures for reform

nad become irresistible. It was felt that the restrictive law endangered the life of the

Mother in addition to the embryo since

numerous women risked irreparable injury and possible death at the hands of the back

,street abortionist. The law punished the Pack-street abortionist who often did his work ror a nominal fee while the more culpable

I Goodbye baby and Amen Peter Evans and Richard Bailey (1969). 2 Ethics Dietrich Bonhoeffer (New York 1965) Pp 175-6. 3 The Month (May 1973).

4

, New York Times Magazine (Jan 8, 1968).

Letter of Andre E. Hellegen M.D.

6 A Biological View Hayes. 7 Sincerity and Authenticity Lionel Trilling (1972 Oxford University Press).

8 Address to the Family Front.

9 Quoted in Abortion on Trial Russel Shaw (Robert Hale 1969).

Abortion on Trial.

The Problems of Abortion: Morality and the Social Facts Professbr Glanville Williams (Faber) p.214. 12 Maccabaean Lectures printed in The Entoremeht oi Morals (Oxford University Press,

10

11

13 1965) /15.

Committee on Homosexual Offences and Prostitution, 1959, Cmd 247.

Harry Camp lectures at Stanford University Printed in Law, Liberty and Morality (Oxford 15 University Press, 1963). 1, On Liberty (London 1859) Chapter 1.

Ibid: Hart p.31 17 18 Ibid: Hart p.33

19 Ibid: Hart, Preface note (May, 1969).

Ibid: Devlin p.89 quoted from Minersville School Dist v Gobitis 310 US, 586 at p.596 (1940) (Frankfurter I). Ibid: Preface p.VIII s p.17.

Ibid: p.95 quoted from The Enforcement of

14

client and prospective father (if around), were called as prosecution witnesses. The measure of protection afforded to the practitioner was uncertain. Inefficient contraceptive methods, an increase in pre-marital intercourse, and social stigma attaching to the mother of an illegitimate child propelled demands for abortion which the law did not sanction. The community's aesthetic sensibilities were upset by the proximity of the rubella and thalidomide tragedies; and the nation developed overnight a cosmic social conscience, resolving to assist in redressing the world population 'imbalance'.

David Steel's private Bill intended to strike a balance between those supporting open abortion and those in favour of entrenchment.

The harassed housewife, the deserted student, the abandoned divorcee, the rapist victim and of course the malformed foetus all had claims for legislative consideration. It was resolved that abortion should be permitted where the mother's physical or mental health was likely to be impaired by a continuation of the preg nancy; or if there were likely to be impairment to the health of her post-natal children.

The doctor could have regard to the woman's present and foreseeable environment when making a decision. Secondly, the pregnancy could be terminated where there was a substantial risk that the child would be born seriously handicapped.'

One would not have thought it beyond the joint efforts of the two assemblies, bent on darifying the law, to give lucid expression to this perfectly coherent compromise. The result was a piece of perplexing verbiage which must rank as a classic of legislative

ineptitude. S.1 (i) (a) authorises an abortion if two medical practitioners form a bona fide

opinion "that the continuance of the preg nancy would involve risk to the life of the pregnant woman, or of injury to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman or any existing children of her family, greater than if the pregnancy were terminated;"" • account may be taken of the woman's actual or reasonably foreseeable environment in determining the risk to health.

Since many doctors now think abortion is safer, at least in the very short term, than normal childbirth it is permissible in all cases.

Naturally, many National Health practitioners would regard this as a forced reading but doubtless many practitioners in private abortion clinics would consider any other in • terpretation as factitious. The Act can claim no spectacular success:

Morals by Dean Rostow (CU Nov. 1960) p.197.

22 Ibid: p.24.

23 Ibid: p.117. 24 See account, Abortion Law Reformed Madeleine Simms and Keith Hindell (Peter Owen Ltd. 1971),

25 Abortion Act, 1967.

26 Simms and Hindell write at p.219: "The number of abortion deaths from all causes fell from fifty in 1968 to thirty-five in 1969."

27 Ibid: R. F. R. Gardner says, "In calculating (back-street abortions) much reliance has been placed on the number of spontaneous or incomplete abortions admitted to hospital. But the figure for these (53,128) in the 12 months after the Act is slightly larger than for the 12 months before the Act came into operation when it was 51,701." Source B.M.J. No. 2 p.259.

28 The number of legal abortions for 1971 in England and Wales was 126,777; for 1972, 159,884 abor tion notifications were made. •

29 Excerpts published in the Observer Review (November 4, 1973) from The Female Woman by Arianna Stassinopoulos (Davis-Poynter).

30 Letter to the Tablet (May 19, 1973): In 1970 65,000 women had illegitimate children but only 9,032 applied for Affiliation Orders of which 7,500 were given.

31 Thw Commission No. 47 set up to look into the law relating to ante-natal injury claims.

32 Watt v Rama 1972VR 353. In the US a court allowed a claim on behalf of an eight month old viable foetus which was still born because of the actionable injury.

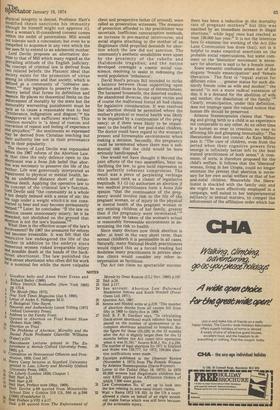

there has been a reduction in the mortality rate of pregnant mothers" but this was matched by an immediate increase in illegal abortions,' while legal ones had reached at least 150,000 last year." It is not the intention here to examine tne working of the Act (the Lane Commission has done that), not is it helpful to make empirical assertions on the probable social repercussions, but some comment on the 'liberation' movement is necessary for abortion is said to be a female issue.

Some semantic confusion arises out of the slogans 'female emancipation' and 'female liberation.' The first is "equal status for different roles ... greater status for such distinctly female roles as wife and mother:" the second "is not a more radical extension of this; it is a demand for the abolition of wife and mother, the dissolution of the family."" Clearly, emancipation, under this definition, does not impinge upon the valued notion that human life should be preserved.

Arianna Stassinopoulos claims that "bearing and giving birth to a child is an experience not comparable to any other. At no other time is a human so near to creation, so near to affirming life and glimpsing immortality." The liberationist does not concur. As Kate Millett puts it: "The care of children, even from the period when their cognitive powers first emerge is infinitely better left to the best trained practitioners of both sexes." A commune, of sorts, is therefore proposed for the child's welfare. It follows that the 'liberated' woman, living in her Utopia, could no longer entertain the pretext that abortion is necessary for her own social welfare or that of her post-natal children. Meanwhile the liberationist is shackled with the family unit and she might be most effectively employed in a campaign, well suited to her temperamental militancy in sexual matters, to compel the enforcement of the affiliation order which has almost fallen into disuse.

"Men," Mary O'Connor points out, "have never been particularly responsible in the sexual field, but until recently it was usually the man who took whatever precautions were necessary in premarital intercourse."" The advent of the pill and easier abortion has changed this and men can now abdicate any responsibility for their acts or omissions.

The recent publicity given to the vasectomy operation might encourage a more responsible male attitude; while reversible sterilisation treatment for women may well be imminent.

But if blame is to be apportioned then the legislature must accept the largest slice. The pre-1967 law was an ass but predictably it gave birth to the unproductive mule which shared some of the parent's traits — ambiguity of intention, pusillanimity in adversity, and insensitiveness to abuse. Oblivious of the implicit contradictions in such a course, Parliament may shortly enact a law giving a child compensatory rights for ante-natal injuries 'I unless the courts anticipate such a move with a satisfactory common law formula. Recently, the Victorian Supreme. Court held that a child had a civil claim in negligence for injuries sustained as a seven week foetus.' It appears, therefore, that compensation can probably be awarded by the courts for accidental injury to a child that survives birth though intentional destruction of a healthy foetus is of course permissible.

Yet despite the deficiencies of the present criminal law, Ian Donald, Glasgow's outspoken professor of midwifery, considers amendment will probably result in minimal retrenchment and might well be a pretext for further concessions. Such opinions mirror a diminishing confidence in the legislative to operate a feasible and balanced abortion policy. Any Act, which is to operate satisfactorily, depends on the good-will of the medical profession and the public, but if it is pliable rather than flexible then the foetal mortality landslide becomes an avalanche.

It may be that the public conscience is immunised against further appeal but the popular myth that abortion is "progressive" can now be exploded. In simplistic terms it is the imposition of an adult scale of values upon incipient youth. In a more meaningful sense open abortion is a rejection of Mill's definitive tenet.

Mill sought to strike a blow for freedom in the conflict, inherent in every society, between state authority and the individual's need for self-expression, but there was one value which he treasured more than freedom itself because it is more radical, more instinctual and more fundamental — the protection of human life. It is indeed ironical that no name comes more readily to the open abortionists' lips than that of Mill. Perhaps Mill would smile sadly at the false champions for he might well think that it is innocent human life, no less, that has been summoned to the bar of reason to justify its existence.

Previous page

Previous page