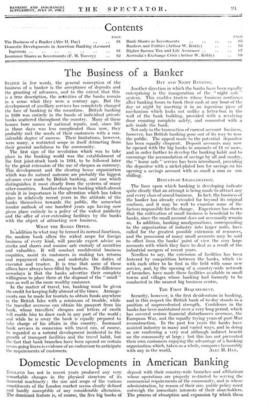

Domestic Development s in American Banking

ENGLAND has not in recent years produced any very remarkable changes in the physical structure of its financial machinery ; the size and scope of the various constituents of the London market seems clearly defined and hardly susceptible of any considerable alteration. The dominant feature is, of. course, the five big banks Of deposit with their country-wide branches and affiliations whose operations are properly restricted to serving the commercial requirements of the community, and in whose administration, by reason of their size, public policy must outweigh the immediate interests of their shareholders. The process of absorption and expansion by which these

great organisations assumed their shape has now ceased with all the discussion it entailed. Suffice it to say that branch-banking on this scale in England was in the main justified by a dividing line drawn roughly between the north and the south, above which money was always needed and below which it was to be freely obtained.

America, however, can still provide excitements both for the holder of bank shares and the student of banking development. There arc in the country some 25,000 independent banking units operating under various charters giving them differing privileges and, of course, varying very greatly in size and character in accordance with the amount of population they serve and its activi- ties. They arc in general prohibited by law from opening branches in other places, and they work in correspondence with others of their number for those of their needs which lie outside their immediate community. As a further distinction it is worthy of note that the larger of these institutions virtually combine a good many of the functions which the London market keeps in separate hands, generally through subsidiary corporations operating as issuing houses, finance companies, investment trusts, &c. An outstanding feature of industrial and commercial development in the post-War period has been the progress of Rationalization, which is the combination of competing concerns with a view to increased profit, and America has proved ideal ground for these experiments with a home market of 120 million people without much traditional prejudice or preference and ready to consume the standard- ized output of mass-production. A great stimulus was, of course, derived from the political and commercial opportunities of the 1Var, which changed the whole aspect of the American economy and accelerated the upward movement in which Rationalization has played such an important part. Banking has naturally had to keep step with this movement and a number of amalgamations have resulted with a view to larger profits and to meeting the requirements of great industrial corporations.

In New York in the last year there took place twenty- eight mergers involving forty-four banks, and the size of the largest American bank has during this period surpassed that of any other institution in the world.

The process has undoubtedly had successful and beneficial results and the institutions thus formed are not yet out of proportion to the size and importance of the New York market, disposing as it does of the surplus funds of the rest of the United States. The money-trust objection is, of course, raised, but the experience of other countries, with the notable exception of Russia, where Socialism appears to have accomplished something of the sort, gives little evidence that there is any danger of such a thing ; on the other hand, the responsibilities of manage- ment must be examined with some reference to human limitations and fallibility and certain it is that the greater the institution the more must the question of the public welfare outweigh considerations of private gain.

So far is so good, but in the light of mythology I confess to some fright at the accumulation which I am told is the later ambition of these giants. Quite naturally, the big banks which have resulted out of the merger process have since turned their attention to the possibility of nation-wide organizations and the repeal of legislation at present preventing them ; in justification of this is urged a pious concern at the insecurity of small country banks, about five thousand of which have failed in the last nine years, affecting deposits of some three hundred million pounds. The fact that the vast majority of these failures were its the same agricultural districts and that seventy per cent. of them had capital of not more than ten thousand pounds seems to imply that a local remedy would be sufficient and that the case might be well met by a legal minimum capital require- Ment of, say, $100,000, and a provision that a town unable to support so large a bank might be privileged to open the branch of a larger institution. ' New York banks have already been able in some eases to extend their sphere of operation by a system now generally described as chain banking, a subterfuge engendered by the branch banking laws. Under this system a subsidiary company of a New York bank acquires, - by .exehange of stock,_ control of-an institution, generally in some large city outside New York or New York State, who in turn, by a similar process, amasses a group of independent banks within its vicinity. Already seven per cent. or about 1,800 banks in America are included in chain organizations controlling about seventeen

per cent. of the aggregate banking resources of the country. On the face of things, however, this particular system is by no means satisfactory and measures must evidently be taken, and in some instances have already been taken, either to prevent it or to exercise a strict control over its operation.

Among the objectionable features that have so far been disclosed is one that although bank stock in America is subject to double liability, in so much as the stock of the banks controlled in a chain organization is in the great majority of cases in the hands of a holding company, the double liability clause is rendered useless once the owner corporation is bankrupt, as it might easily be if the elements of the chain are unsound. Furthermore, the mobility of reserves, which branch banking accom- plishes, has no satisfactory substitute in the chain system.

In practice, a good deal of the movement up to now has been undertaken for speculative profit and there have been almost as many signs of jobbery in bank stocks as of concern for the security of the public's money. The financial interests into whose hands control of these chains is finding its way are in many cases not banking organizations at all, and it has been remarked that they show a tendency to avail themselves of the privileges which ownership entails by borrowing freely from their banks.

The subject is occupying a great deal of attention, but the suns of it all is that no comparison between the banking systems of England and America has more than a scientific interest in the widely different circumstances of the countries which the banks serve, but that a process of controlled evolution in such matters is evidently more desirable than revolutionary legislation to repeal the existing banking laws and the chaotic competitive scramble which would follow.

LEONARD INGRAMS.

Previous page

Previous page