Exhibitions 2

Traffic Art: Rickshaw Painting from Bangladesh (Museum of Mankind, till May 1991)

Transport of delight

John Henshall

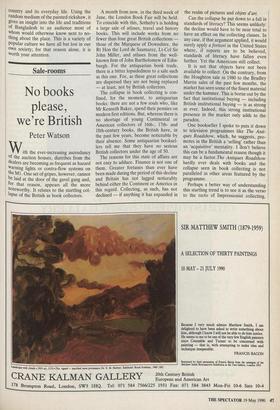

0 f all the myriad art forms of the modern world, the 'untutored' vernacular art of the Indian subcontinent must stand out, for Western observers, as one of the most vibrant and expressive. Two aspects are particularly striking: one is its apparently effortless blend of the tradition- al imagery of Islam and Hinduism — those most uneasy bedfellows — with often quite surreal pop art whose range and vivacity rival anything Warhol and company could manage; the other is its startlingly garish colours which, coupled with a clinically realist style, give it the bizarre but unmis- takable impression of being 'painted photography'. Anyone who has visited those fascinat- ing enclaves of the eastern and western extremes of London, long colonised by emigres from the subcontinent and their increasingly westernised offspring, and has seen the cinema posters, advertisement hoardings and simple shop window signs in their tantalising Urdu or Hindi script, will know what I mean. This singular phe- nomenon is on view in the exhibition These panels from a backplate between the wheels on a rickshaw show animal paintings, common in rickshaw art. The upper panel shows a small bird feeding a cuckoo, which may be an indirect form of social criticism. The lower panel shows a tiger confronting a white horse — this alludes to violence in human society.

Traffic Art at the Museum of Mankind (6 Burlington Gardens, W1) for the rest of this year, and into the next. It is with this exuberant pictorial medium, drawing simultaneously on the fads of the hour and the culture of a millennium, that the mainly Muslim rick- shaw drivers of Bangladesh decorate the seat-backs and side-panels of their now largely pedal-powered vehicles. It is esti- mated that some three million Bangla- deshis depend on rickshaws for a preca- rious living, whether driving, servicing, manufacturing or painting them. In a desperately poor nation of some hundred million souls, rickshaws are often the only practical, affordable means of transport. Most of the 50 or so exhibits here are drawn from a field collection commis- sioned by the museum and assembled in the Bangladeshi capital, Dhaka. Dhaka has some 150,000 tricycle rickshaws, com- prising two-thirds of all traffic on a road system barely suitable for many other types of vehicle. The rickshaws are among the most picturesquely decorated vehicles in the world, rivalling the painted jeeps of Manila or the farm wagons of Sicily. This exhibition includes entire rickshaws, but mainly features their exquisitely decorated panels: these are documented by detailed captions which also describe the artists and drivers, and are set in context by photo- graphs of the vehicles in their native milieu. We see a bewitching array of often disparate images: scenes from the Koran and Hindu gods and goddesses jostle the latest film and rock stars; we relive the 1971 war which won Bangladesh independ- ence from Pakistan and cost a million lives. Among the mythological and legendary, we also see the real: here are Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, leader of the freedom fighters, the Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore, and even the Prince and Princess of Wales on their wedding day — a scene evidently cribbed from a biscuit tin! The great and the good are mercilessly satirised as humanoid animals in clothes, engaged in suitably improbable or ridiculous activities. Then there are images dictated by Islamic convention: for example, women discreetly portrayed as beauteous peacocks, doves or lovebirds, side by side with deliberately provocative disco dancers with spray-on Levis and come-hither looks. There are women astronauts, pictures of mosques, minarets and the Taj Mahal, fabulous sea monsters and snow-capped mountain peaks the artists can never have seen. As for the baddies, we know them at once: bright blue and green faces have a fetching distinction, after all. Visions of a future, prosperous Bangladesh proliferate.

This is an original and engrossing exhibi- tion, and I hope many who know Bang- ladesh mainly through reports of flood and disaster will go to see it, to store in their minds another image of an extraordinary country and its everyday life. Using the random medium of the painted rickshaw, it gives an insight into the life and traditions of Bangladesh to an audience most of whom would otherwise know next to no- thing about the place. This is a variety of Popular culture we have all but lost in our own society; for that reason alone, it is worth your attention.

Previous page

Previous page