Festival of film and fantasy

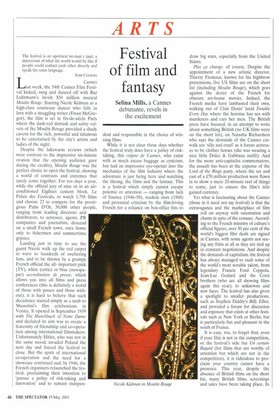

Selina Mills, a Cannes debutante, revels in the excitement

The festival is an apolitical no-man's land, a microcosm of what the world would be like if people could contact each other directly and speak the same language.

Jean Cocteau

LCannes ast week, the 54th Cannes Film Festival kicked, sung and danced off with Baz Luhrmann's lavish $50 million musical Moulin Rouge. Starring Nicole Kidman as a high-class courtesan dancer who falls in love with a struggling writer (Ewan McGregor), the film is set in fin-de-siècle Paris where the dark-red damask and sultry velvets of the Moulin Rouge provided a shady cavern for the rich, powerful and infamous to be entertained by the city's artists and ladies of the night.

Despite the lukewarm reviews (which were contrary to the impressive six-minute ovation that the opening audience gave during the credits), Moulin Rouge was the perfect choice to open the festival, showing a world of contrasts and extremes that rarely come together. For ten days a year, while the official jury of nine sit in an airconditioned Eighties cement block, Le Palais des Festivals, to watch 1,798 films and choose 23 to compete for the prestigious Palm D'Or, 30,000 other people, ranging from leading directors and distributors, to actresses, agents, PR companies and journalists, descend on a small French town, once home only to fishermen and summertime gypsies.

Landing just in time to see the gaunt Nicole walk up the red carpet to wave to hundreds of sweltering fans, and to be thrown by a grumpy French official the allimportant pink (TV), white (critic) or blue (newspaper) accreditation de presse, which allows you into all films and press conferences (this is definitely a world of those with passes and those without), it is hard to believe that such decadence started simply as a snub to Mussolini's film celebrations in Venice. It opened in September 1939 with The Hunchback of Notre Dame and declared its aim was to create a fraternity of friendship and co-operation among international filmmakers. Unfortunately Hitler, who was not in the same mood, invaded Poland the next day and forced the festival to close. But the spirit of international co-operation and the need for a showcase continued and. by 1946, the French organisers relaunched the festival, proclaiming their intention to 'pursue a policy of risk-taking and innovation' and to remain indepen

dent and responsible in the choice of winning films.

While it is not clear these days whether the festival truly does have a policy of risktaking, this virgine de Cannes, who came with as much excess baggage as cynicism, has had an impressive eye-opener into the mechanics of the film industry where the adventure is just being here and watching the throng, the films and the fantasy. This is a festival which simply cannot escape polemic or attention — ranging from lack of finance (1948-50), student riots (1968) and perennial criticism by the film-loving French for a reliance on box-office hits to

draw big stars, especially from the United States.

Plus ca change, of course. Despite the appointment of a new artistic director, Thierry Fremaux, known for his highbrow pretensions, five US films are on the short list (including Moulin Rouge), which goes against the desire of the French for obscure art-house movies. Indeed, the French media have lambasted their own, walking out of Clair Denis' lurid Trouble Every Day where the heroine has sex with murderers and eats her men. The British press have focused, in an attempt to write about something British (no UK films were on the short list), on Natasha Richardson who says the demands of the Cannes catwalk are 'silly and cruel' as it forces actresses to be clothes horses (she was wearing a nice little Dolce & Gabbana outfit). And for the more anti-capitalist commentators, the assault has been at the expense of the Lord of the Rings party, where the set and cast of a £70 million production were flown in to show a mere 20-minute reel of things to come, just to ensure the film's title gained currency.

Yet what is fascinating about the Cannes (those in it need not say festival) is that the extravaganza and the marketplace of film roll on anyway with ostentation and charm in spite of the censure. According to the French ministry of culture's official figures, over 50 per cent of the world's biggest film deals are signed at Cannes, with some agents not seeing any films at all as they are tied up in constant negotiations. And despite the demands of capitalism, the festival has always managed to exalt some of the world's most notable talent, from legendary Francis Ford Coppola, Jean-Luc Godard and the Coen brothers (who are all showing films again this year), to unknowns and new faces. The festival has also given a spotlight to smaller productions, such as Stephen Daldry's Billy Elliot, and provided a forum for discussion and exposure that exists at other festivals such as New York or Berlin, but is particularly fun and pleasant in the south of France.

It is easy, too, to forget that, even if your film is not in the competition, or the festival's side bar Un certain Regard (for films that are worthy of attention but which are not in the competition), it is ridiculous to proclaim your country cannot have a presence. This year, despite the absence of British films on the short list, many British films, screenings

and sales have been taking place. In

the first three days of the festival alone, the BBC announced a £106 million deal with a film financing house to fund bigger budget movies; FilmFour has screened Crush starring Andie MacDowell; and Bafta nominees Luke Ponte, Luke Morris and Toby Macdonald are showing their short, Je raime John Wayne, during the directors' fortnight. With Julia Ormond on the jury, it is hard to say there is no British presence here this year.

Away from the media circus there is also something wonderfully luminous about Cannes which you only get a chance to consider in the quiet hours of the early morning, as you walk home along the famous Croisette, past the vast army of workers clearing up the bottles from the previous night's carousing and a Swedish director who was convinced I would be perfect for his new movie. Cannes may be budgets, box offices and a rat race full of mobile phones singing the Star Wars theme, but it is also a lavish, bizarre world of zeal where the creation of image, in all its guises, is exalted, There is something unique and refreshing, like seeing a new painting for the first time, in experiencing the full force of a film being shown for the first time, without the preconceptions of mass reviews, and to sit in an auditorium where the viewers clap, boo and hiss, immune to the hype surrounding the launch.

There is something invigorating, too, about being in the Palais where every language in the world is being spoken purely about film (even if it is about money for the film), and where directors and producers are answerable for their work not only to the media. but to their professional colleagues. Being jammed into a press hall the size of a tin can is certainly not a particularly pleasant experience, but hearing Francis Ford Coppola talk about the re-editing of a film he made 22 years ago (Apocalypse Now) was like listening to Tolstoy discussing the writing of War and Peace.

As every physicist knows, theory and practice are not always the same, and whoever the jury announces on Sunday as the winner (Moulin Rouge and Dreamwork's computer-animated Shrek are hotly tipped), there is sure to be an outcry from the bolsheviks that the choice is against the the festival's aims of promoting innovation and taking risks. True, too, there will be thousands of obscure foreign language films that no one will recall next month as well as the exhausting round of parties that are gaudy, glamorous and rarely intelligent. But even if it's a show of vulgarity, there is something liberating and amusing in such a complicated mesh of humanity where high art merges with hustlers, hopefuls, seedy porn stars and aging collagen-lipped women whose hopes of getting a screen test are as unlikely as their hair colour. Crass, commercial and surreal it certainly is, but there is a certain passion in its crassness that can only be admired. For my sins, I am off to another party.

Previous page

Previous page