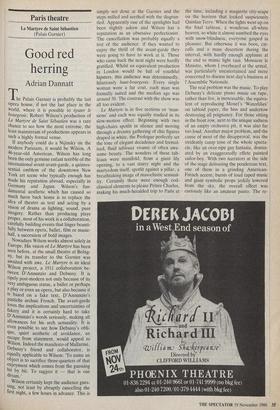

Paris theatre

Le Martyre de Saint Sebastien (Palais Gamier)

Good red herring

Adrian Dannatt The Palais Gamier is probably the last Opera house, if not the last place in the world, where it is possible to epater le bourgeois. Robert Wilson's production of Le Martyre de Saint Sebastien was a rare chance to see how the most extreme, the least mainstream of productions appears in such a highly formal venue.

If anybody could do a Nijinsky on the modern Parisians, it would be Wilson. A 46-year-old American, Wilson has long been the only genuine enfant terrible of the international avant-avant-garde, a quintes- sential emblem of the downtown New York art scene who typically enough has made his reputation abroad, especially in Germany and Japan. Wilson's fun- damental aesthetic which has caused so much furor back home is to replace the idea of theatre as text and acting by a vision of drama as lighting, sound, pure imagery. Rather than producing plays proper, most of his work is a collaboration, carefully building events that linger beauti- fully between opera, ballet, film or music- hall, a succession of bold images. Nowadays Wilson works almost solely in Europe. His vision of Le Martyre has been seen before, at the small theatre at Bobig- ny, but its transfer to the Gamier was awaited with awe. Le Martyre is an ideal Wilson project, a 1911 collaboration be- tween D'Annunzio and Debussy. It is ripely post-modern not only because of its very ambiguous status, a ballet or perhaps a play or even an opera, but also because it is based on a fake text, D'Annunzio's pastiche archaic French. The avant-garde loves the implications and uncertainties of fakery and it is certainly hard to take D'Annunzio's words seriously, making all allowances for his arch sensuality. It is even possible to see how Debussy's obli- que, quiet aesthetic of avoidance, an escape from statement, would appeal to Wilson. Indeed the manifesto of Mallarme, Debussy's friend and collaborator, is equally applicable to Wilson: 'To name an object is to sacrifice three-quarters of that enjoyment which comes from the guessing bit by bit. To suggest it — that is our dream.'

Wilson certainly kept the audience gues- sing, not least by abruptly cancelling the first night, a few hours in advance. This is

simply not done at the Gamier and the steps milled and seethed with the disgrun- tled. Apparently one of the spotlights had been slightly askew and Wilson has a reputation as an obsessive perfectionist. The cancellation was probably equally a test of the audience: if they wanted to enjoy the thrill of the avant-garde they were going to have to work at it. Those who came back the next night were hardly gratified. Whilst an equivalent production in London would be full of youthful hipsters, this audience was determinedly, hilariously haut-bourgeois. Every single woman wore a fur coat, each man was formally suited and the median age was around 50. The contrast with the show was all too evident.

Le Martyre is in five sections or 'man- sions' and each was equally studied in its slow-motion effect. Beginning with two high-chairs spotlit in silence and moving through a dreamy gathering of chic figures draped in white, the Prologue perfectly set the tone of elegant decadence and formal- ised, fluid tableaux vivants of often awe- some beauty. The wonders of these tab- leaux were manifold, from a giant lily opening, to a vast starry night and the martyrdom itself, spotlit against a pillar, a breathtaking image of masochistic sensual- ity. Certainly there were enough cod- classical elements to please Prince Charles, making his much-heralded trip to Paris at

the time, including a maquette city-scape on the horizon that looked suspiciously Quinlan Terry. When the lights went up on the final tableau, a wondrous all-white heaven, so white it almost numbed the eyes with snow-blindness, everyone gasped in pleasure. But otherwise it was boos, cat- calls and a mass desertion during the interval, with hardly enough applause at the end to mimic light rain. Monsieur le Ministre, whom I overheard at the urinal, was particularly unentertained and more concerned to discuss next day's business at l'Assemblie Nationale.

The real problem was the music. To play Debussy's delicate piano music on tape, rather than live, is inexcusable, the equiva- lent of reproducing Monet's 'Waterlilies' on tabloid paper, the hiss and undertow destroying all poignancy. For those sitting in the front row, next to the unique sadness of an empty orchestra pit, it was also far too loud. Another major problem, and the cause of most of the disapproval, was the stridently camp tone of the whole specta- cle, like an over-ripe gay fantasia, domin- ated by an exaggeratedly effete painted sailor-boy. With two narrators at the side of the stage delivering the ponderous text, one of them in a grinding American- French accent, bursts of loud taped music and giant symbolic props jerkily lowered from the sky, the overall effect was curiously like an amateur panto. The re- freshing innocence, the dead-pan naivety which are Wilson's trademarks, looked, in this grand setting, like mere clumsiness.

There is a lesson here for Covent Gar- den, presently trying to work out how it can accommodate the more avant-garde of spectacles, how it should adapt to the modern, fashionable young audience, how it can rival the modish reputation of the ENO with its own funky shows — don't.

Previous page

Previous page