Exhibitions 2

The Fallen (MoMA, Oxford, till 15 January) The Renaissance of Gravure: The Art of S. W. Hayter (Ashmolean, Oxford, till 27 November)

Oxford reflections

Giles Auty

Driving to Oxford last week I recalled how close I came once to entering the museum service. In 1967 I was offered the job of director of a funded art gallery in that city. Fortunately or otherwise, what the consequences of my taking that posi- tion might have been for art in Oxford or elsewhere — will never be known. I remember that what I wanted to do was shake up the complacency which tradi- tionally infested publicly funded outlets but I felt, at the time, that the odds against achieving this were overwhelming. The era was one in which the ubiquitous protagon- ists of hard-line modernism never doubted their moral superiority for a moment. Modern art galleries were stiff with such folk who, on the whole, recognised and appointed none but their own. By contrast, my belief then and now is that the term `modern' in art should embrace all art made within the modern epoch and not just a partial, innovation-biased selection from it. Why should the public support the idea of artistic innovation in preference to that of excellence when the two qualities do not often or necessarily coincide? In the end, I decided not to take the job because I could foresee a losing battle with the modern museum hierarchy. Life is too short for the fruitless martyrdom of trying to achieve changes from within; our Royal Heir is lucky that he does not now have to try to make his living as an architect.

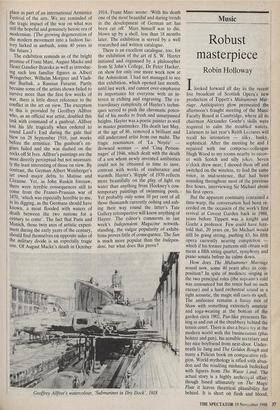

The foregoing notwithstanding, I am glad to report that the current exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford is of genuine quality and interest and eschews for once the art-as-prophylactic didacticism encountered so often in such places: 'you may not like it but it's good for you.' Here there is much to like, at the moment at least. The exhibition features the work a number of young or youngish artists had been doing when their lives were cut short by the first world war. This show takes place as part of an international Armistice Festival of the arts. We are reminded of the tragic impact of the war on what was still the hopeful and genuinely heroic era of modernism. (The growing degeneration of the modern movement into a fashion fac- tory lurked in ambush, some 40 years in the future.) The exhibition reminds us of the bright promise of Franz Marc, August Macke and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska as well as introduc- ing such less familiar figures as Albert Weisgerber, Wilhelm Morgner and Vladi- mir Burliuk, a Russian Futurist. Partly because some of the artists shown failed to survive more than the first few weeks of war, there is little direct reference to the conflict in the art on view. The exception to this is provided by Geoffrey Allfree who, as an official war artist, doubled this task with command of a gunboat. Al!free lost his life tragically when ordered to round Land's End during the gale that blew on 28 September 1918, just weeks before the armistice. The gunboat's en- gines failed and she was dashed on the rocks off St Ives. Allfree's paintings are the most directly perceptual but not necessari- ly the least interesting of those on view. By contrast, the German Albert Weisberger's art owed major debts to Matisse and Cezanne. Yet, as John Ruskin foresaw, there were terrible consequences still to come from the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, 'which was especially horrible to me, in its digging, as the Germans should have known, a moat flooded with waters of death between the two nations for a century to come'. The fact that Paris and Munich, those twin axes of artistic experi- ment during the early years of the century, should find themselves on opposite sides of the military divide is an especially tragic One. Of August Macke's death in October 1914, Franz Marc wrote: 'With his death one of the most beautiful and daring trends in the development of German art has been cut off.' Marc himself was to die, blown up by a shell, less than 18 months later. The exhibition is served by a well researched and written catalogue.

There is an excellent catalogue, too, for the exhibition of the art of S. W. Hayter initiated and organised by a philosopher from St John's College, Dr Peter Hacker, on show for only one more week now at the Ashmolean. I had not managed to see this exhibition, which opened last month, until last week, and cannot over-emphasise its importance for everyone with an in- terest in etching and engraving. The ex- traordinary complexity of Hayter's techni- ques served to push the chromatic poten- tial of his media to fresh and unsurpassed heights. Hayter was a poetic painter as well as master printmaker. His death last May, at the age of 86, removed a brilliant and still underrated artist from our midst. The tragic resonances of 'La Noyee' drowned woman — and 'Cinq Person- nages' of 1946, which dealt with the death of a son whom newly invented antibiotics could not be obtained in time to save, contrast with works of exuberance and warmth. Hayter's 'Ripple' of 1970 reflects more beautifully on the play of light on water than anything from Hockney's con- temporary paintings of swimming pools. Yet probably only some 10 per cent of all those thousands currently oohing and aah- ing their way round the latter's Tate Gallery retrospective will know anything of Hayter. The editor's comments in last week's Independent Magazine notwith- standing, the vulgar popularity of exhibi- tions proves little of consequence. The Sun is much more popular than the Indepen- dent, but what does this prove?

Geoffrey Allfree's watercolour, 'Submarines in Dry Dock', 1918

Previous page

Previous page