Exhibitions

Toulouse-Lautrec (Hayward Gallery, till 19 January) Francesco Clemente (Royal Academy, till 27 October)

Little Toulouse

Giles Auty

Presumably artists who have been the subjects of popular films are also sure-fire hits at the art gallery box office. To get the picture one has only to think of such exam- ples as Van Gogh, Gauguin or Toulouse- Lautrec. But do not popular films also diminish somehow the pleasure we derive from art? Many can never think of Van Gogh now without Mr Douglas's prog- nathous features swimming into vision. Whichever Mr Ferrer it was who played the filmic Toulouse-Lautrec did so with his lower legs strapped painfully behind him. How do I know this? No doubt from some colour magazine of yesteryear. Such facts are typical of colour supplement pap, where supposed editorial is so often noth- ing more than disguised publicity for forth- coming films or exhibitions. The world of colour supplements and popular films may bear some faint resemblance to life or his- tory, yet it is life or history with most or all of the essential, illuminating elements removed. I imagine such extraction is made to help greater humanity identify with worlds of which they know little or nothing.

On the day of my visit, a brace of show- girls peered excitedly at Toulouse-Lautrec's paintings of cabaret, rather as horse- fanciers might have done at an exhibition by Munnings. A show of works by Toulouse-Lautrec is one of the hardest at which to strip away surrounding nonsense and nostalgia and get down to the art. Numberless reproductions of the artist's paintings and posters bring on a retinal numbness which I find easier to cope with, for some reason, in the cases of Gauguin and Van Gogh. Toulouse-Lautrec drew with facility and panache from an early age. His tendency to stylise line and towards caricature was apparent already and is the quality which least engages me.

Toulouse-Lautrec's singular way of using oil paint gives the look of some other medi- um such as pastel or crayon and con- tributes further to a feeling of insubstantiality. Lines and dabs of different colours within a similar tonal range con- tribute also to diffusion and ethereality. Perhaps it is perverse of me to like late, less typical works by the artist in which darker and denser blocks of colour con- tribute to greater solidity. 'Messalina Seat- ed on a Throne' and 'An Examination at the Faculty of Medicine' are easy to over- look right at the end of the show, which is hung chronologically. The great brothel Painting of the salon at the Rue des Moulins is similarly dark and sonorous. A posed monumentality supplants the more Informal, spontaneous-looking appearance of earlier renderings of this and related subjects.

The society Toulouse-Lautrec painted was generally that of the demi-monde who inhabited cafés-concerts and maisons closes. The exhibition catalogue which, from an early section entitled 'Conditions of Class and Gender' promised to be pompous or worse, provides sensible historical insights into the complex world of boulevardier and Insoumise:

The marginal, quiet maison close was at once a contrast to the brash, extrovert café-concert and yet also consistent, for the prostitute, like the star, was a unit in the economy of Parisian entertainment. As Lautrec's friend Victor Joze put it in 1894: 'The bourgeois, in Spite of his diatribes against such "vice", is basically very satisfied with the way prostitu- tion works. He gets pleasure from these women just like he does from the theatre, from cafés, from little visits to Switzerland.'

Toulouse-Lautrec's vision of such a world 15 generally humane: neither jaundiced, Prurient nor apparently condescending. To make art from the mundane was, of course, one of the leading tenets of the artistic and literary realism which prevailed at the time. What the reality of places such as the Moulin-Rouge was, or that of other Mont- martre entertainments, is hard to gauge. Yet while Toulouse-Lautrec helped popu- larise, glamorise and even immortalise such affairs, the truth was probably more sordid and violent. The artist lived at a time when art and society were in a continuous and rapid process of change. His paintings and equally important graphic works give us some taste of the time and provoke in many a yearning for the kind of Paris that has not existed now for more than a life- time.

I wonder whether a popular film will ever be made about Francesco Clemente. A walk around the Royal Academy's Sack- ler Galleries at present will surely imprint that artist's unusual features indelibly on the memory. What else the casual visitor there will remember is uncertain but I doubt it will be the distinction of the artist's Powers of drawing which, unlike those of Toulouse-Lautrec, are sadly limited. By Contrast with Toulouse-Lautrec, who left us

with an interesting historical record of the life and mores of his time, Clemente is self- obsessed in a manner common now among artists who possess a shortfall in ability allied to an excess of adulation from the museum world.

Clemente, who was born in Naples in 1952, has lived almost since boyhood along the fringes of the experimental arts. At 12 his parents arranged for a book of his childhood poems to be published. Perhaps as a result of the trauma this must have induced Clemente has subsequently befriended or greatly admired a wide spec- trum of other would-be gurus: Joseph Beuys, Andy Warhol, Julian Schnabel, Rene Ricard, Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, Jack Kerouac. Telling of his admira- tion for Ricard, Clemente wrote;

He is not possessed by a tragic destiny, only an exceptional objectivity. He has never owned a book, and if he speaks of things he has read it is as if he heard them from a voice — but whose and when and where? Hungry and exhausted, he asks for a $30U loan, only to return with a $350 bouquet, obtained at a discount. .

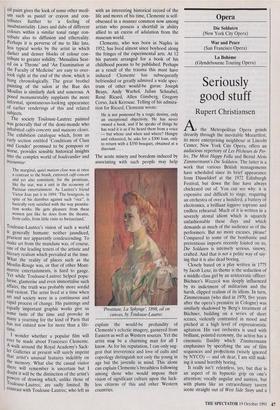

The acute misery and boredom induced by associating with such people may help 'Prostitute, La Sphynge', 1898, oil on canvas, by Toulouse-Lautrec explain the would-be profundity of Clemente's eclectic imagery, garnered from Eastern as well as Western sources. Yet the artist may be a charming man for all know. As for his reputation, I can only sug- gest that irreverence and love of cults arid coprology distinguish not only the young in age but the juvenile in mind. This alone can explain Clemente's breathless following among those who would impose their vision of significant culture upon the luck- less citizens of this and other Western countries.

Previous page

Previous page