MEETING ONE OF HISTORY'S FOOTNOTES

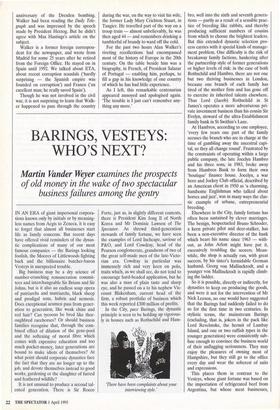

Simon Courtauld shares a drink with Alan

Walker, Lord Curzon's cipher clerk, and still going strong at 100

IT WAS 11 o'clock in the morning, we were sitting in a converted cowshed on the downs above Froxfield, on the Berkshire- Wiltshire border, and Alan Walker, who celebrated his 100th birthday last Decem- ber, asked me to join him in a glass of vodka.

`It's one of the holy trinity,' he said, `with caviar and champagne; though I don't have so much of them. I suppose I have been enjoying vodka fairly regularly since I was in Moscow in the 1930s.' Walk- er was head of chancery at the British embassy between 1930 and 1933.

He raised his glass. 'Here's to Yeltsin though I wonder if he'll survive after that imbecile invasion of Chechnya. Russia is quite powerful enough to withstand the temporary loss of one of its outlying prin- cipalities.'

In spite of his great age, Walker reads without difficulty and remains highly artic- ulate. He is wearing a scarlet woollen shirt, tweed jacket and sharply pressed trousers. His diction is precise, and when he pronounces a foreign word — whether in Russian, Serbo-Croat, French, German or Spanish — it is evident that he still retains his lifelong talent for languages. When I refer to the Moskovskaya brand of vodka, Walker rebukes me for placing the accent on the third, rather than the second, syllable.

He apologises for being unable to remember anything, then proceeds to recall incidents with remarkable clarity. 'I was in the embassy garden with Litvinov [then Soviet foreign minister, or commissar for foreign affairs, as Walker calls him] and Lady Astor and Beatrice and Sidney Webb. Lady Astor was pleading with Litvinov to allow someone to leave Russia, but she didn't get anywhere.

`And the Webbs were talking about this great new earthly paradise, this "new civili- sation". Utter balls — there was nothing particularly civilised about the Lubyanka.

`Then there was that other fellow-trav- eller, Malcolm Muggeridge of the Manch- ester Guardian — he was visiting Moscow around this time. I think I had some influ- ence in turning him against communism; I helped to decontaminate him.'

My conversation with Alan Walker took place on 14 February, St Valentine's Day, but he informs me that, much more signifi- cantly, it is the day of St Cyril and Method- ius, who brought Christianity to eastern Europe in the 9th century and introduced the Cyrillic alphabet.

`It was said that Stalin had been destined for the priesthood in the Russian Orthodox Church. I remember once seeing him at a meeting of Soviet delegates, when I was seated at a table with the diplomatic corps. As he approached the platform I said, in a loud voice and in Russian, "There's His Majesty," which caused some amusement. My friends in the commissariat for foreign affairs used to say that, when Stalin's name was mentioned in conversation, a momen- tary silence would follow.'

The name of Alan Walker deserves to be included in the footnotes of history. Apart from his diplomatic career, he was in Ger- many before the first world war, served on the Western Front in 1917, and on Lord Curzon's staff at a German reparations conference, travelled through Spain during the civil war and returned to Germany after 1945. Before Moscow, Walker had been in Riga, as secretary to the British minister for Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia, Sir Hughe Knatchbull-Hugessen, who famous- ly complained to his Foreign Office mas- ters, in the form of a parody of the Athanasian creed, when Walker, the only English member of his staff, was taken from him and transferred to the Soviet Union (The Spectator, 7 September 1991).

`I don't think "Snatch" was on his own for too long,' Walker said. 'In those days the Baltic states were very pleasant, well organised societies. I remember getting to know one of the Estonian Baltic barons, who had an ancestor who had inspired Beethoven's Goldberg Variations.'

Walker caught up with Knatchbull- Hugessen again in Turkey in 1939, this time as first secretary to Ambassador Snatch.

`The Turks found his name rather diffi- cult to deal with. An invitation to a trade fair in Smyrna was addressed to Sir Huge Catchbull.'

On his way back from Ankara to Lon- don in the summer of 1941, Walker met de Gaulle in Cairo.

`He said he had recently seen Churchill and told him the Allies were cornered in the eastern Mediterranean. When I asked how Churchill had reacted to this, de Gaulle — who was usually so solemn, like an enormous presiding deity — burst out laughing.'

Walker retired from the Foreign Office at the end of the war, aged 50; but his diplomatic career had gone back a long way. In 1920 he was working for the For- eign Secretary, Lord Curzon, as his per- sonal cipher clerk, at the Spa conference. Lloyd George was there 'doing all the talk- ing', and also the French Prime Minister, Clemenceau. (`Hadn't he been a Commu- nard in 1871?' Walker asked. 'Clemenceau once made the oracular statement that the most useless thing in the world was prostate gland — a sentiment with which I have good cause to agree.') Later that year he was posted to Belgrade, where he had to deal with the 'beastly Balkan people'.

`I never really liked the Serbs.,' Walker said. 'It was all so much better under Aus- tro-Hungary. Today the nastier kind of Serb is making war in Bosnia. Karadzic is a bad man; I'd bump him off myself if I had the chance.'

It was time for another drop of vodka, and to go back 80 years — to the Great War. Walker volunteered for the front in 1914 but, because he was short-sighted, was drafted into the Army Service Corps. By 1917, however, his country needed him in the trenches, and he joined the territori- al division of the Royal Warwickshire regi- ment. It was the 61st, more commonly known as the 60-worst.

`On the day we arrived at the front, I leapt down into a trench and the mud and water went over my knees. The combina- tion of the rain and all the recent born- bardments, which had caused the soil to disintegrate, made the mud quite appalling.

`I spent about five months in the trench- es, but it was very quiet — an occasional exchange of shots but no fighting. We were at the southern end of the line, next to the French, who were very generous with their wine. There was one German trench raid on another of our battalions nearby, but the first we knew of it was from a report in the Paris edition of the Daily Mail, which was passed up the line.

`Then I got trench fever — from the lice — and was sent home via hospital in Rouen. I missed the Ludendorff offensive, so this illness probably saved my life. Right at the end of the war I was ordered to take about 30 men out to France. The reserve battalion in Dover thought that was the last they would see of me, but as soon as I had delivered my men I was told to return to England. I think it was the .week that Wilfred Owen was killed.'

My rather pathetic attempt to recite the first few lines of Owen's 'Anthem for Doomed Youth' was trumped by Walker quoting, nearly word-perfect, from his favourite war poet, Siegfried Sassoon:

I'd like to see a tank come down the stalls, Lurching to rag-time tunes, or 'Home, sweet Home', - And there'd be no more jokes in music-halls To mock the riddled corpses round Bapaume.

Walker had been to Germany in 1911, staying with a family in Dusseldorf, where he remembers being told that the German army could be in Paris within a fortnight.

`And it was there that I bumped into an old schoolfriend [from the Perse School, Cambridge] called Dutt, who was half- Swedish and half-Parsee. We met in the street, and while we were talking a police- man came and said, `Stehen verboten!' (Ironically, in the light of Walker's posting to the British embassy in Moscow, Dutt was to become the first secretary of the British Communist Party.) Walker was next in Diisseldorf in 1947, as interpreter to the four-power control commission inspecting war damage all over Germany. The city looked pretty bad, but my clearest memory is of hearing a very good performance of Ariadne auf Naxos there.

`The destruction of Dresden was appalling to ape, and the bombing had been quite pointless. I had been there in the 1930s and remembered the Frauenkirche and the Palace of the Kings of Saxony what an abomination that raid was.

The head of the Russian delegation who, incidentally, was much more agree- able than the British, American and French representatives on the commission — said to me, "You did such a good job of flatten- ing Dresden that I cannot find anywhere to billet my staff."' We were talking on the day after the anniversary of the Dresden bombing. Walker had been reading the Daily Tele- graph and was impressed by the speech made by President Herzog. But he didn't agree with Max Hastings's article on the subject.

Walker is a former foreign correspon- dent for the newspaper, and wrote from Madrid for some 25 years after he retired from the Foreign Office. He stayed on in Spain until 1992. We talked about ETA, about recent corruption scandals (`hardly surprising — the Spanish empire was founded on corruption') and Franco Can excellent man; he really saved Spain').

Though he was not involved in the civil war, it is not surprising to learn that Walk- er happened to pass through the country during the war, on the way to visit his wife, the former Lady Mary Crichton Stuart, in Tangier. He travelled part of the way on a troop train — almost unbelievably, he was then aged 44 — and remembers drinking a tumblerful of brandy to ward off the cold.

For the past two hours Alan Walker's riveting recollections had encompassed most of the history of Europe in the 20th century. On the table beside him was a biography, in French, of President Salazar of Portugal — enabling him, perhaps, to fill a gap in his knowledge of one country of which he has had little experience.

As I left, this remarkable centenarian appeared annoyed and apologised again. `The trouble is I just can't remember any- thing any more.'

Previous page

Previous page