Thirty years on

Julie Burchill

MARILYN'S MEN by Jane Ellen Wayne Robson, £16.95, pp. 217 QUEEN OF DESIRE: MARILYN MONROE — A FICTION by Sam Toperoff Picador, £14.99, pp. 276 MARILYN AND ME — SISTERS, RIVALS, FRIENDS by Susan Strasberg Doubleday, f14.99, pp. 218 MARILYN: THE LAST TAKE by Peter Brown and Pattie Barham Heinemann, £17.50, pp. 436 Upon her death in 1962, Marilyn Monroe ceased to be a film star and became a myth; some time in the Seventies, she ceased to be simply a myth and became an industry. Or perhaps a vocation; books on her do not sell well compared to books on royalty, Provence or the meaning of life. But people still flock in droves to write them: Norman Mailer, Gloria Steinem, her ex-friends, her ex-husbands, her ex- servants. And hacks in packs, of course. Watching a boxing match, it is silly to ask why the boxers are there. Far more strange

and unwholesome are the reasons why the spectators are there. In the same way, three of these books tell us far more about their authors than they do about their subject. They are, basically, one scissors- and-paste job; one sexual fantasy; one creepy friend-of-the-famous, victim-of- dysfunctional-family effort of the type currently so popular in America; and, thank the Lord, one serious and impressive work of exhaustively researched investiga- tive journalism.

The joke now, of course, is to say 'So where can I get the first three?' Lots of people, myself included, enjoy reading gossip and smut about famous people. But I don't like reading it about Monroe. It was this gift — of inspiring love as much as lust — which has made her legend so durable, so resistant to changing tastes, and which has made her even more popular with women than with men; who, I think, tend to be more attracted by the less complicated, freewheeling sexual style of the Sixties Brigitte Bardot.

Marilyn was a very modern woman; no sexual primitive or sunny hippie swinger, she. Complex, driven, demanding, self- absorbed and an early convert to the dubi- ous pleasures of psychoanalysis, she ceaselessly revealed, re-invented and de- constructed herself in interviews. In a way, this is the problem for writers; Marilyn was never qu', always `vous', even to those of her admirers born a decade after her death on a different continent. We feel we know her so well that it is hard for a book to tell us anything new; in the case of the first two, they don't even seem to have tried. And in the case of Susan Strasberg, she tells us too much of the things we guessed at, but don't want our noses rubbed in.

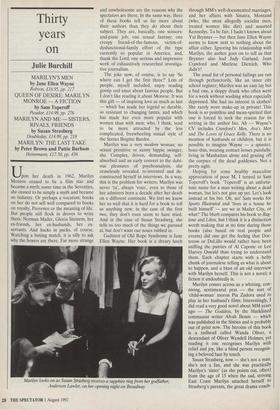

Guiltiest of Old Rope Syndrome is Jane Ellen Wayne. Her book is a dreary lurch Marilyn looks on as Susan Strasberg receives a sapphire ring from her godfather, Anderson Lawler, on her opening night on Broadway through MM's well-documented marriages, and her affairs with Sinatra, Montand (who, like most allegedly socialist men, treated women like dirt) and assorted Kennedys. To be fair, I hadn't known about Yul Brynner — but then Jane Ellen Wayne seems to know next to nothing about the affair either. Ignoring his relationship with Marilyn, the author goes on to tell us that Brynner also had Judy Garland, Joan Crawford and Marlene Dietrich. Who didn't?

The usual list of personal failings are run through perfunctorily, like an inner city school register; Marilyn was an easy lay but a bad one, a sloppy drunk who often went for a week without washing when especially depressed. She had no interest in clothes! She rarely wore make-up in private! This book is so pointless and mean-spirited that one is forced to seek the reason for its writing in the author bio. Ah — Wayne's CV includes Crawford's Men, Ava's Men and The Loves of Grace Kelly. There is no mention of husbands or children, but it is possible to imagine Wayne — a spinster, bone-thin, wearing contact lenses painfully, living in Manhattan alone and grazing off the corpses of the dead goddesses. Not a pretty sight.

Hoping for some healthy masculine appreciation of poor M, I turned to Sam Toperoffs book. `Toperoff is an unfortu- nate name for a man writing about a dead woman, but let's not give up yet. Let's look instead at his bio. Oh, no! Sam works for Sports Illustrated and 'lives in a house he built himself — are we in Mailer City, or what? The blurb compares his book to Rag- time and Libra, but I think it is a distinction worth making that at no time during those books (also based on real people and events) did one get the feeling that Doc- torow or DeLillo would rather have been sniffing the panties of Al Capone or Lee Harvey Oswald than trying to understand them. Each chapter starts with a hefty chunk of journalese telling us what is about to happen, and a blast of an old interview with Marilyn herself. This is not a novel; a fiction it undoubtedly is.

Marilyn comes across as a whining, con- niving, sentimental prat — the sort of `child-woman' moron Pia Zadora used to play in her husband's films. Interestingly, I did read a very good novel about MM years ago — The Goddess, by the blacklisted communist writer Alvah Bessie — which was published in the Sixties and is probably out of print now. The heroine of this book is a redhead called Wanda Oliver, a descendant of Oliver Wendell Holmes; yet reading it one recognises Marilyn with relief and joy, like a blind person recognis- ing a beloved face by touch.

Susan Strasberg, now — she's not a man, she's not a fan, and she was practically Marilyn's 'sister' (as she points out, often) from the age of 15 when the sad, striving East Coast Marilyn attached herself to Strasberg's parents, the great drama coach- es Lee and Paula, a few years before her death. Marilyn attached herself to many families during her lifetime; she particular- ly loved old women, and continued her relationships with the parents of ex-lovers and husbands long after she had dumped their sons. Naturally, most old broads and buffers were knocked out by this radiant creature's attention; the streetwise Stras- bergs demanded a little more, as Lena Pepitone — Marilyn's maid, confidante and 'Baby Lamb' — recorded with sharp- eyed Sicilian cynicism during her years with Marilyn:

The Strasbergs always frightened me. Neither ever smiled. He was a small man with an intense sneer. Paula was less intimidating, though anything but a fun person. 'I couldn't get a line out without her,' Marilyn said. 'And she protects me on the set. Paula's my friend.' Paula's value to Marilyn, if 1 recall correctly what Marilyn said, was reflected in the huge salary she drew — almost two thou- sand dollars a week (in the Fifties.) I had first assumed that the Strasbergs were help- ing Marilyn out of friendship, but she was forever writing cheques to them. 'They really need the money,' she would say in a con- cerned voice.

I'm sure that Marilyn is smiling some- where as she watches Susan Strasberg's book go on sale; that's SUSAN STRASBERG — ACTRESS AUTHOR TEACHER, as the horribly illiterate press handout screams. How's this for pure, embarrassing Americana?

Her one-woman autobiographical evening in the theatre, Growing Pains and other Pleasures, which she wrote and directed, is a tapestry of scenes from Shakespeare, Jules Feiffer, Dorothy Parker, interwoven with personal stories and anecdotes.

Yes, Marilyn is dead — and they're still minting it off her.

There can be no doubt that Strasberg was as close to Marilyn as all we worship- pers have yearned to be; envy is invariably an element of disliking this book, as we glower resentfully at the photographs of Marilyn cuddling the author, or presenting her with a Chagall for her birthday. It gets worse in the text, wherein Marilyn parades naked before Strasberg during one of their numerous sleepovers. There is a particular- ly heartbreaking photograph, completely unsensational, of Marilyn looking as beau- tiful as heaven and sitting to one side, gazing wistfully, as Strasberg's god- father gives her his mother's sapphire ring on her opening night on Broadway. In one picture, Marilyn's yearning for family, con- tinuity and theatrical respectability is com- bined.

To cap it all, there is even a snapshot of the young, incredibly luscious Richard Bur- ton gazing at the young Strasberg (she was quite beautiful) with unashamed lust. This woman has really lived; that is why her Insistence on capitalising on the Marilyn myth seems so pitiful. By the way, Stras- berg is currently working on a book about her father; does this give new meaning to the term 'relative value'?

After these grubby, clammy, touchy-feely books, it is a relief (for once) to come across a big brute work of investigative reporting, complete with Kennedys, wicked studios and conspiracy theories galore. Strangely enough, this huge book presents a far more original, recognisable and sym- pathetic portrait of Monroe than do any of the intimate little numbers. Perhaps, in the case of those most alive on the screen, a view from some distance gives a truer picture than a view from under the floor- boards.

Previous page

Previous page