ARTS

Exhibitions 1

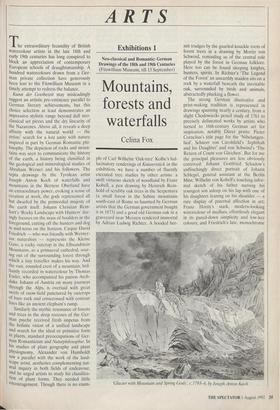

Neo-classical and Romantic: German Drawings of the 18th and 19th Centuries (Fitzwilliam Museum, till 13 September)

Mountains, forests and waterfalls

Celina Fox

The extraordinary fecundity of British watercolour artists in the late 18th and early 19th centuries has long conspired to block an appreciation of contemporary European schools of draughtsmanship. A hundred watercolours drawn from a Ger- man private collection have generously been lent to the Fitzwilliam Museum in a timely attempt to redress the balance.

Kunst der Goethezeit may misleadingly suggest an artistic pre-eminence parallel to German literary achievements, but this choice selection at least demonstrates an impressive stylistic range beyond dull neo- classical set pieces and the dry linearity of the Nazarenes. Above all, it reveals a deep affinity with the natural world — the artists' search for a lost unity with nature inspired in part by German Romantic phi- losophy. The depiction of rocks and moun- tains was seen to communicate the history of the earth, a history being classified in the geological and mineralogical studies of Abraham Werner and his followers. The sepia drawings by the Tyrolean artist Joseph Anton Koch of waterfalls and mountains in the Bernese Oberland have an extraordinary power, evoking a sense of creation at work, the gods represented all but dwarfed by the primordial majesty of the earth itself. Johann Christian Rein- hart's 'Rocky Landscape with Hunters' dar- ingly focuses on the mass of boulders in the foreground, cutting off the hunters and dog in mid-torso on the horizon. Caspar David Friedrich — who was friendly with Werner- ian naturalists — represents the Kleine Gans, a rocky outcrop in the Elbsandstein Mountains, as a primaeval cathedral, soar- ing out of the surrounding forest through which a tiny traveller makes his way. And the vast, rounded crest of a mountain, bril- liantly recorded in watercolour by Thomas Ender, who accompanied his patron Arch- duke Johann of Austria on many journeys through the Alps, is overlaid with great swirls of snow-field punctured by outcrops of bare rock and crisscrossed with contour lines like an ancient elephant's rump.

Similarly the mythic resonance of forests and trees in the deep recesses of the Ger- man psyche received fresh impetus from the holistic vision of a unified landscape and search for the ideal or primitive form in plants, standard preoccupations of Ger- man Romanticism and Natuiphilosophie. In his studies of plant geography and plant Physiognomy, Alexander von Humboldt saw a parallel with the work of the land- scape artist, aesthetics complementing nat- ural inquiry in both fields of endeavour, and he urged artists to study his classifica- tion of plant forms. They needed little encouragement. Though there is no exam-

ple of Carl Wilhelm 'Oak-tree' Kolbe's hal- lucinatory renderings of Krauterstiick in the exhibition, we have a number of fluently executed tree studies by other artists: a swift virtuoso sketch of woodland by Franz Kobel!, a pen drawing by Heinrich Rein- hold of scrubby oak trees in the Serpentara (a small forest in the Sabine mountains south-east of Rome so haunted by German artists that the German government bought it in 1873) and a good old German oak in a graveyard near Meissen rendered immortal by Adrian Ludwig Richter. A hooded her- mit trudges by the gnarled-knuckle roots of forest trees in a drawing by Moritz von Schwind, reminding us of the central role played by the forest in German folklore. Here too can be found sleeping knights, hunters, spirits. In Richter's 'The Legend of the Forest' an unearthly maiden sits on a rock by a waterfall beneath the inevitable oak, surrounded by birds and animals, abstractedly plucking a flower.

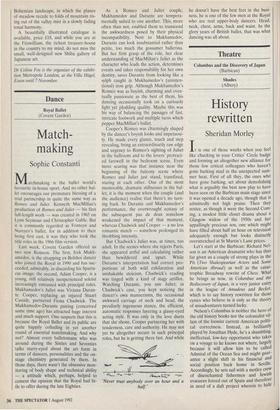

The strong German illustrative and print-making tradition is represented in drawings spanning nearly a century, from a slight Chodowiecki pencil study of 1761 to precisely delineated works by artists who turned to 16th-century German art for inspiration, notably Diirer prints: Pieter Cornelius's title page for the 'Nibelungen- lied', Schnorr von Carolsfeld's 'Jephthah and his Daughter' and von Schwind's 'The Return of Count von Gleichen'. But for me the principal pleasures are less obviously contrived: Johann Gottfried Schadow's unflinchingly direct portrait of Johann Schlegel, general assistant at the Berlin Mint; Wilhelm von Kobell's touching infor- mal sketch of his father nursing his youngest son asleep on his lap with one of his daughters leaning on his shoulder — a rare display of paternal affection in art; Franz Horny's stark, modern-looking watercolour of medlars, effortlessly elegant in its pared-down simplicity and low-key colours; and Friedrich's late, monochrome 'Glacier with Mountain and Spring Gods', c.I793-4, by Joseph Anton Koch Bohemian landscape, in which the planes of meadow recede to folds of mountain ris- ing out of the valley mist in a slowly fading tonal harmony.

A beautifully illustrated catalogue is available, price £18, and while you are at the Fitzwilliam, the richest treasure-house in the country to my mind, do not miss the small, well-designed new Shiba gallery of Japanese art.

Dr Celina Fox is the organiser of the exhibi- tion Metropole London, at the Villa Hugel, Essen until 7 November.

Previous page

Previous page