CHESS

Stupor mundi redux

Raymond Keene

In a press conference in Belgrade last week, the sensational news was announced that Bobby Fischer is to emerge from his two decades of hibernation to contest an exhibition match `for the World Cham- pionship' against his old rival Boris Spass- ky. The prize fund is 5 million US dollars. The promoter of the match, Mr Jezdimir Vasiljevic, proprietor of a Belgrade bank, announced at the press conference that Fischer had already arrived in Belgrade. The match will begin on 1 September in the Yugoslav town of Milocev. The players will stay on the island of Sveti Stefan in a villa once belonging to President Tito. The match will switch to Belgrade as soon as one player has five wins to his credit. The conditions for this contest are those that Fischer had demanded, but which the World Chess Federation had rejected, for the 1975 match with Karpov which never took place. This match will continue until one player wins ten games. The winner will get 3.35 million US dollars and the loser 1.65 million, by a huge margin the largest prize ever offered for a chess competition, and significantly a million dollars more than for the official world championship match — Short or Timman against Kaspar- ov — which is scheduled for Los Angeles in August 1993.

Although previous efforts to lure Bobby Fischer out of hiding have proved consis- tently abortive, this latest initiative has the ring of truth. Fischer himself is back to his old contentious form and in a vintage utterance, castigating the current world champion, Gary Kasparov, and his eternal rival, Anatoly Karpov, added that he had studied the matches between Kasparov and Karpov for a year and a half and will prove that the matches between the two, who are officially the world's top two chessplayers, were 'fixed'.

Sources in Chicago close to Bobby Fis- cher, now balding and bearded with a dome-like brow, quite different from the lanky, athletic young man who won the world championship in 1972, claim that Fischer has been deeply moved by the recent death, in his mid-fifties, of the former world champion, Mikhail Tal. Tal had been Fischer's rival and friend in the late 1950s and 1960s and his death appears to have galvanised Fischer into action.

A further element in Fischer's return has been a desire to enrage the world estab- lishement by playing in Yugoslavia. The match is likely to be viewed as violating the international sanctions against Yugoslavia imposed by the UN to stop the fighting in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In former years the only offers which seriously attracted Fischer were those to play in South Africa. Mr Vasiljevic said, expanding on this theme: 'By bringing Fischer to Yugoslavia, we have broken the blockade in a most spectacular manner. The world hit us with all its force and we have returned at least one punch. We practically had to abduct Fischer from the airport in Budapest be- cause we were afraid they might take his passport and ban him from entering Yugoslavia. Bobby still considers himself the world champion, because no one ever beat him'.

In 1975, Fide, the World Chess Federa- tion, stripped Fischer of his title when he refused to defend against the then challen- ger Anatoly Karpov. Fischer is the only player in the history of world cham- pionship chess to have lost his title by default. Fischer is now 49, Spassky 55. By modern chess standards, with the world's youngest master, London's Luke McShane, being only eight years old, the two legendary titans are veterans. Fischer has not played a game in public for 20 years, but if he can revive the old sparkle this will be a memorable match.

This week I recall past glories with Fischer's best win from the great match against Spassky in 1972.

Fischer — Spassky: World Championship (Game 6), Reykjavik 1972; Queen's Gambit Declined.

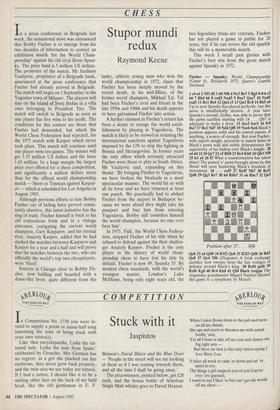

1 c4 e6 2 Nf3 d5 3 d4 Nf6 4 Nc3 Be7 5 Bg5 0-0 6 e3 h6 7 Bh4 b6 8 cxd5 NxdS 9 Bxe7 Qxe7 10 NxdS exd5 11 Rcl Be6 12 Qa4 c513 Qa3 Rc8 14 Bb5 a6 Up to now Spassky has played perfectly, but this move is insufficiently incisive. A year later Spassky's second, Geller, was able to prove that the pawn sacrifice starting with 14 . . . Qb7 is adequate to make a draw. 15 dxc5 bxt5 16 0-0 Ra7 17 Bet Nd7 18 Nd4 Qf8 19 Nxe6 fxe6 Black's position appears solid and his central pawns, if anything, a source of strength. But now Fischer, with superb insight, proceeds to punch holes in Black's pawn wall and subtly demonstrates the superionty of his bishop over Black's knight. 20 e4 d4 21 f4 Qe7 22 e5 Rb8 23 Bc4 Kh8 24 Qh3 Nf8 25 b3 a5 26 f5 What a transformation has taken place! The passed `e' pawn brought about by this thrust will soon hamstring Black's freedom of movement. 26 . . . exf5 27 RxfS Nh7 28 Rcfl Qd8 29 Qg3 Re7 30 h4 Rbh7 31 e6 Rbc7 32 Qe5 Position after 37 . . . Nf6 Qe8 33 a4 Qd8 34 R1f2 Qe8 35 R2f3 Qd8 36 Bd3 Qe8 37 Qe4 Nf6 (Diagram) A brisk exchange sacrifice now sweeps away the last vestiges of defence around Black's king. 38 Rxf6 gxf6 39 Rxf6 Kg8 40 Bc4 KM 41 Qf4 Black resigns The Argentine grandmaster Miguel Najdorf likened this game to a symphony by Mozart.

Previous page

Previous page