Exhibitions 2

Houghton Hall: The Prime Minister, the Empress and the Heritage (Kenwood House, till 20 April)

Stately grandeur

Annabel Ricketts

his Prime Minister, Sir Robert Walpole, was a corpulent Norfolk squire (it was said that his stomach protruded at least a yard beyond his nose) who affected a convincing provincial coarseness with rowdy hunting cronies. In fact, despite never having done the Grand Tour and cutting a very different figure from the beruffled dandies recently seen at the Tate, he assembled a collection that contempo- raries recognised as the most important in Britain.

In the 18th century, the fame of Houghton, his great Palladian showcase, and its contents was unrivalled: the house was the first to inspire a monograph while Boydell devoted an entire publication to the pictures. Two stray facts (culled from the excellent catalogue) underline the scale of Walpole's ambition. Housekeeping costs were reported to be £1,500 a week and it was said that 110 beds could be made up at an hour's warning.

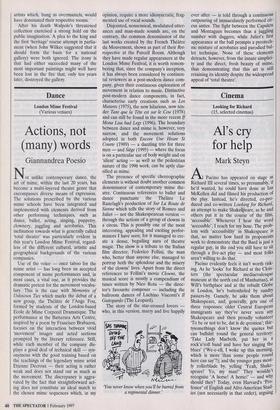

This is a small exhibition with ambitious aims. It explores Walpole's role as patron; it considers the relationship between the house and its contents; it tells the story of the enforced sale of the pictures to Cather- ine the Great (the result of huge debts); and it raises questions about both 18th-cen- tury and present-day attitudes to what is now called 'heritage' but which is in reality the movement of works of art in tune with the ebb and flow of national and personal Kent's proposed design for the elevation with picture hang of the north wall of the Saloon fortunes. This shopping list of aims accounts for the cumbersome title.

The most daunting task is to recreate the dazzling splendour of both house and col- lection in a handful of relatively modest rooms. The organiser, Andrew Moore, suc- ceeds decisively both because of the intrin- sic quality of the major objects, which include furniture, sculpture, paintings and silver, and because of the imagination and care that went into his selection. Drawings, such as Rysbrack's cartoon for an overman- tel relief, and letters, such as the one dis- cussing the alterations which made Houghton's gallery the first in England to be top lit, highlight aspects of craftsman- ship or design. Most intriguing are Kent's beautifully worked proposals for the Saloon which show in charming detail the ceiling decoration and the positions of identifiable pictures. Not only do Kent's drawings convey the richness of the hang but, since none of the pictures on loan retain their Kentian frames, they also sug- gest their original appearance.

The grandeur of the exhibits increases as the exhibition unfolds. Thus, the simple chairs and pewter plates designed to sur- vive rumbustious hunting parties on the lower floor contrast with the rich mahogany furniture, complete with original upholstery, from the Saloon. It is perhaps the attention to detail that is most captivat- ing: for instance, the finely worked fish- scale carving used to set off the richness of the gilding on the furniture, or the delicate engraving (attributed to Hogarth) of the fabulous Walpole salver.

But it is Walpole's doomed picture col- lection that forms the heart of the exhibi- tion. Catherine the Great, who understood the value of great art in enhancing power and prestige, also knew a bargain when she saw one. Paying £36,000 (some £4,000 less than the valuation), the Empress acquired 181 pictures — everything in fact except the family portraits. Once she had her claws on them, she said, she would, like a cat with a mouse, never let them go. Six pictures are reunited here with objects still in the collection. Three come from the Hermitage, and three from America where they have been since their sale by the Sovi- et Union in the 1920s. In 1975, a seventh, the intriguing portrait by Kneller of Joseph Carreras, was bought back by the Chol- mondeleys (descendants of the Walpoles) and returned to hang once more in one of the family rooms, the Common Parlour.

Like the furniture, the pictures show the carefully controlled increase of grandeur and it is the three pictures originally from the State Apartments that form the climax of the exhibition. A portrait of Innocent X, attributed to Velasquez, represents the small pictures which crowded together in opulent density in the Cabinet Room. The noble Poussin of the Holy Family and the glorious portrait of Clement IX by Maratti (both from Russia) are examples of pic- tures by two of Walpole's most favoured artists which, hung as overmantels, would have dominated their respective rooms.

After his death Walpole's threatened collection exercised a strong hold on the public imagination. A plea to the king and the first 'heritage' rescue attempt in parlia- ment (when John Wilkes suggested that it should form the basis for a national gallery) were both ignored. The irony is that had either succeeded many of the most important paintings might well have been lost in the fire that, only ten years later, destroyed the gallery.

Previous page

Previous page