AMENDMENT OF THE POOR LAWS. ENGLISH

t... AND FRENCH SYSTEMS. VERY man in England above the station of a pauper is galled ore or less by the burden of the poor-rates; which have gone on

' increasing year after year, in spite of Parliamentary Committees and speech-making, and essay-writing, almost without end. Farms : lying waste, and houses untenanted, attest the magnitude of the evil. The absolute necessity of providing some remedy for it, or at least of striving to mitigate its ruinous consequences, is acknow- ledged by all ; and even the Government has at last condescended to make the amendment of the Poor-laws a Cabinet measure. " The Poor-law Commissioners have just published a massy Re- port, in which many new regulations are recommended for adoption; and if their suggestions are followed, they consider it certain that " the expenditure for the relief of the pour u ill in a very short pe- riod be reduced by more than one third." This would give a relief to the country of nearly three millions a year. And when we call to mind the jobbing and mismanagement which pervade almost every part of our present system, and the vast diminution of ex- pense which has followed the adoption of better rules for support- ing the poor in other countries, and in some cases even in our own, we feel convinced that the Commissioners have not exaggerated the benefits likely to flow from the substitution of honest and discreet for fraudulent and foolish management. The recommendations of the Commissioners will .be condemned by those who arc utterly opposed to the system of compulsory re- lief for the poor in any shape. But the duty of the Commissioners was to inquire into the administration and operation of the Poor- laws, and to suggest remedies for the evils which they found. Besides, the abolition of Peor-laws in England, even supposing it were desirable, is under present circumstances scarcely practi- cable. It is therefore the part of wisdom to strive to alleviate what must always be an onerous tax. The Commissioners, with this view, appear to have adopted a sound principle on which to base their suggestions to the Legislature and the public. They lay it down as a fundamental position, that in no case should the condition of the pauper be as eligible as that of an independent labourer of the lowest class. At present, it is notorious that in many parishes it is far preferable. The abolition of out-door re- lief; the employment of paupers in really useful work, instead of compelling theta to carry baskets loaded with stones, and to dig holes only to till them up again ; the union of small parishes for the sake of maintaining their poor under one roof; the simplifica- tion of the laws of settlement; and the abolition of the existing bastardy laws, the fruitful source of perjury and prostitution; all these are improvements which, if carried into effect, will assuredly tend greatly to produce the result foretold by the Commissioners.

The evidence on which the Report is founded has not yet been given to the public. However, five volumes of 500 pages each are forthcoming. Doubtless the number might have been quad- rupled, and yet abundant evidence of the jobbing and mismanage- ment prevalent in the administration of Poor-laws would be left unrecorded. While, however, the abuses of the present system are so constant and prevalent, it fortunately happens that the Commissioners are not left entirely to their own invention or sa- gacity to devise remedies for them. Some parishes have had the experience of good as well as bad management of their poor, and the rest of the nation may profit by it. If we understand the Report, nearly all the measures which are recommended have proved successful, when tried. Ignorance and corruption have been the cause of their being tried in so few parishes. It becomes, therefore, the peculiar duty of the Legislature to interfere, and to compel the universal adoption of them; and we trust that the present session of Parliament will not pass over without a thorough remodelling of the whole Poor-law system. The land- ow ners, if we may credit their oft-repeated asseverations, are peculiarly interested in the speedy completion of this work. They maintain that nearly the whole burden of pauperism rests upon their shoulders. If this be true, they will derive a benefit propor- tionably large from a diminution of the present cost of supporting the poor. Let the advocates l'or a repeal of the Corn-laws re- member this, and strive to obtain a remodelling of the Poor-laws.

That the Commissioners speak within bounds when they antici-

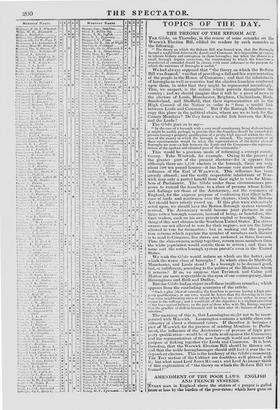

pate a reduction in the cost of maintaining the English poor to the extent of one third, we are the more inclined to believe, from an examination of the cost of providing for the French paupers. On this subject there is a useful and interesting artiele in the last Foreign Quarterly Review. In France, there is at present no system of compulsory relief; but in the capital there are twelve " Bureaux de Bienfaisance," each with twelve managers, assisted by an indefinite number of Charity Committees. The number of

persons employed in this work is about 1,700; each manager, or Dame de Charity, visiting a certain number of families varying

from 10 to 20. The average of families relieved in 1823 and 1824 was 29,981; of individuals, 60,340. The relief aftbrded is princi-

pally in goods, not money,—an excellent arrangement, and one which, by the abolition of out-door relief, must generally be adopted tinder the Workhouse system recommended by the English Com- missioners. Under the French system, the numbers applying for relief (not receiving it), in Paris, have by no means increased in proportion with the increase of population. In 1791, there were 118,000; in 1804, 86,000; in 1813 (the year of the Russian cam- paign), 102,000; but in 1826, there were only 86,000 applicants, in a population of nearly a million. It is to be observed, that they only receive relief from the Bureaux de Bienfaisance, who are re- 'ported by the visiters to stand in pressing need of it, no person in

France having a legal claim. This is not the case as regards the

Foundling Hospitals, which are established on the same principle in some respects as the English Poor-laws. From 1819 to 1824,

the number of foundlings in the French hospitals increased from 99,000 to 116,000.

The Bureaux de Bienfaisance are established in the French provinces, though they are not so efficient as in Paris. In thirteen departments, with a population of nearly five millions, there are 585

bureaux. The result of this system is, that while in England the money expended on the poor was in 1829 2/. 3s. 10(1. per head, in the metropolitan departments of France it was not quite 1s., and in thirteen provincial departments only 41d. There are many other curious pieces of information on this subject in the article before-mentioned in the Foreign Quarterly ; but what we have quoted will be sufficient to prove that the calculation of a reduotion of one third in the cost of maintaining the poor in England, to arise from an improved system of management, is not an extrava- gant one, but rather under the mark.

It may be said, that the facts stated and the course of our ar- gument go to prove the advantage of an entire abolition of the system of compulsory relief to the poor. If we had now for the first time to discuss the question of the expediency or inexpedi- ency of establishing a system of Poor-laws similar in principle to our own, the facts we have stated would go a considerable way in assisting the solution of the problem. But, as we have already said, the entire abolition of the present system seems impracticable. This is a point, however, which it is beside our purpose now to argue. Enough has been adduced to show clearly the very great reduction of poor-rates which would result from adopting some of the regulations of the French Bureaux de Bienfaisance. The great excess also in the number of persons relieved in England over those in France, goes to prove that in the former country a large proportion of paupers are not so from necessity. Of this fact the Poor-law Commissioners appear to be fully convinced.

Previous page

Previous page