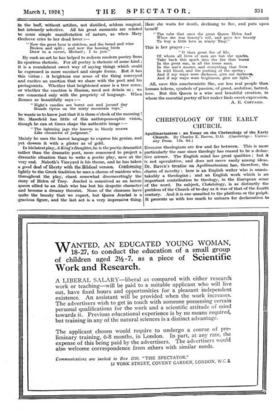

CHRISTOLOGY OF THE EARLY CHURCH.

ENGLISH theologians are few and far between. This is more particularly the case since theology has ceased to be a deduc- tive science. The English mind has great qualities ; but it is not speculative, and does not move easily among ideas. Dr. Raven's treatise on Apollinarianism has, therefore, the charm of novelty : here is an English writer who is unmis- takably a theologian ; and an English work which is an important contribution to theology, in the European sense of the word. Its subject, Christology, is as distinctly the problem of the Church of to-day as it was of that of the fourth century. And it is one unsuited to the platform or the pulpit. It presents us with too much to unlearn for declamation to

be either reasonable or useful ; the discussion is one for the Theological School.

The writer's main thesis is " that there was an early doctrine about Christ based on genuine memory and tradition, and that this doctrine was superseded by one derived from the Hellenic conception of the Logos of God who became incarnate." Its home was Antioch ; its typical representative Theodore of Mopsuestia—" if the Alogi are the first Christian critics, Theodore is the first exponent of the historical method " : the Logos .doctrine was Alexandrian, and its most consistent exponent Apollinarius of Laodicea—according to Jiilicher, " the ablest, most influential, and most prolific writer of his age." There were, indeed, other tendencies at work :—

" Few pictures of early Christianity are more wildly inaccurate than that which imagines the Apostles as starting upon their work equipped with a precise system of theological dogma. If we can free ourselves from the besetting tendency to read back into the past the formularies and conventions established by centuries of patient experiment, we shall recognize that these results were, reached by a process of evolution. . . . The present position of the study of psychic phenomena supplies a parallel to that of Christian theology in the second century."

The comparison is ingenious, and to bear in mind the position indicated is the beginning of wisdom. For it is in this sa'cluni denixo.., as it has been called, that the origins of theological

science are to be found.

The initial error, and it was one which increased with years;

was the metaphysical bias. This was acknowledged by divines of unquestioned orthodoxy. Compellimus ineffabilia eloqui, says St. Hilary ; and in our own time, Duchene; writing of the disasters occasioned by these controversies : " Tel fut le prix de ces exercises metaphysiques ! " It should; however, be remembered that, in the long run, the common

sense of the Church disavowed the extravagances of specula- tion. St. Augustine is the Doctor of Grace, but Catholic theology is not Augustinian ; Cyril prevailed at Ephesus, but his " One Nature " doctrine was modified in the sense of its opponents. From the first the instinct of the Christian consciousness has been to leave conflicting propositions lying side by side unreconciled rather than to risk the loss of religious values by synthesis : the attempt—to_ redress the balance between Theodore and Apollinarius, in this sense, has precedent on its side. That it should have been undertaken is a hopeful

sign TOT theology ; which, in this matter at least, is-harder and stiffer in the modern than it was in the ancient or even in

the mediaeval Church. The school of Antioch needs rehabilita- tion. As compared with its great rival, it represents " a wholly different method of approach ".to the religious prob- lems now as of old in question ; between the two " there is the same divergence as between the moderns and the tradi- tionalists of to-day." When we think elf Christ, it is well to begin not with the Divine Nature, of which we know little, but with the Human, of which we may know much. If we do so, new horizons will open to us ; we shall look for a union " along moral rather than metaphysical lines."

ALFRED FAWKES.

Previous page

Previous page