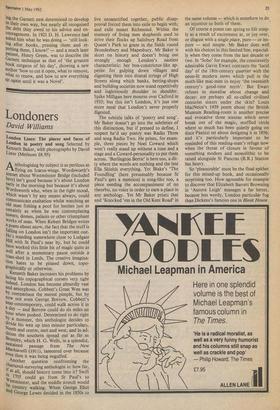

Londoners

David Williams

London Lines: The places and faces of London in poetry and song Selected by Kenneth Baker, with photographs by David Lister (Methuen £6.95) Anthologising by subject is as perilous as flying on Icarus-wings. Wordsworth's sonnet about Westminster Bridge (included here) isn't good because it's about London earlY in the morning but because it's about wordsworth who, when in the right mood, Which wasn't by any means always, could communicate exaltation whilst watching an old man fishing a pool for leeches just as certainly as when he was contemplating towers, domes, palaces or other triumphant works of man. When Robert Bridges writes a Poem about snow, the fact that the stuff is falling on London isn't the important one. 1.1„,..e's standing somewhere close to Ludgate Pall with St Paul's near by, but he could have worked this little bit of magic quite as well after a momentary pause outside a tram-shed in Leeds. The creative imagina- tion hates to be pinned down, topo- graphically or otherwise. , Kenneth Baker increases his problems by !acing his topographical corsets very tight indeed. London has become absurdly vast and amorphous. Cobbett's Great Wen was by comparison the merest pimple, but by now not even George Borrow, Cobbett's near-contemporary, could walk across it in a day — and Borrow could do six miles an hour when pushed. Determined to do right by a monster, this anthologist decides to divide his wen up into minute particulars. North and centre, east and west, and in ad- dition the southern spread out as far as ,13r°1-nleY, which H. G. Wells, in a splendid, sustained passage from The New Machiavelli (1911), lamented over because even then it was being engulfed. Another question confronting the Chartered-surveying anthologist is: how far, if at all should history come into it? Swift In 1705 could go from St Paul's to estminster, and the middle stretch would °e country walking. When George Eliot and George Lewes decided in the 1850s to live unsanctified together, public disap- proval forced them into exile to begin with; and exile meant Richmond. Within the memory of living men shepherds used to drive their flocks up Salisbury Road from Queen's Park to graze in the fields round Brondesbury and Mapesbury. Mr Baker is short on history and doesn't bring out strongly enough London's nastiest characteristic: her boa-constrictor-like ap- petite for gulping down villages and digesting them into dismal strings of High Streets along which banks, betting-shops and building societies now stand repetitively and ingloriously shoulder to shoulder. Spike Milligan here mourns over Catford in 1933; but this isn't London, it's just one more meal that London's never properly digested.

The subtitle talks of 'poetry and song'. Mr Baker doesn't go into the subtleties of this distinction, but if pressed to define, I suspect he'd say poetry was Radio Three and song Radio Two. He prints, for exam- ple, three pieces by Noel Coward which won't really stand up without a tune and a stage and a Coward-personality to put them across. 'Burlington Bertie' is here too, a dit- ty where the words are nothing and the late Ella Shields everything. Yet Blake's 'The Foundling' (here presumably because St Paul's gets a mention) is song-like too, a piece needing the accompaniment of no theorbo, no voice in order to earn a place in any anthology. Yet Mr Baker prints that and 'Knocked 'em in the Old Kent Road' in the same volume — which is somehow to do an injustice to both of them.

Of course a poem can spring to life simp- ly as a result of excitement at, or joy over, or disgust with a single place, pure — or im- pure — and simple. Mr Baker does well with his choices in this limited line, especial- ly when they come from the last decade or two. In 'Soho' for example, the consistently admirable Gavin Ewart contrasts the 'lucid day' of the 18th-century quartier with the neon-lit modern stews which pull in the moth-like mac-men to enjoy 'the twentieth century's good-time myth'. But Ewart refuses to moralise about change and decay: are perhaps all so-called civilised centuries sisters under the skin? Louis MacNeice's 1939 poem about the British Museum Reading-room is another precise and evocative three stanzas which never break out of the magic, muffled circle where so much has been quietly going on since Panizzi set about designing it in 1856; and it's particularly important to be reminded of this reading-man's refuge now when the threat of closure in favour of something modern and monolithic to be raised alongside St Pancras (B.R.) Station lies heavy.

So 'pleasurable' must be the final epithet for this mixed-up book, and occasionally surprising too. How agreeable for example to discover that Elizabeth Barrett Browning in 'Aurora Leigh' manages a far better, because less wordy, London particular fog than Dickens's famous one in Bleak House.

Previous page

Previous page