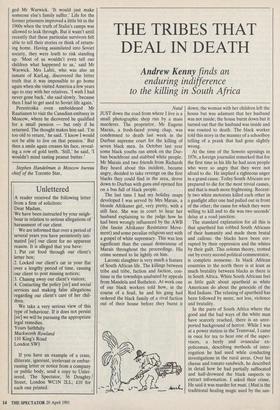

THE TRIBES THAT DEAL IN DEATH

Andrew Kenny finds an enduring indifference to the killing in South Africa

Natal JUST down the road from where I live is a small photographic shop run by a mass murderer. The proprietor, Mr Eugene Marais, a fresh-faced young chap, was condemned to death last week in the Durban supreme court for the killing of seven black men. In October last year some black youths ran amok on the Dur- ban beachfront and stabbed white people. Mr Marais and two friends from Richards Bay heard about this incident, became angry, decided to take revenge on the first blacks they could find in the area, drove down to Durban with guns and opened fire on a bus full of black people.

The last time I had my holiday snaps developed I was served by Mrs Marais, a blonde Afrikaner girl, very pretty, with a still face. She was in court to hear her husband explaining to the judge how he had been wrongly influenced by the AWB (the fascist Afrikaner Resistance Move- ment) and some peculiar religious sect with a gospel of white supremacy. This was less significant than the casual demeanour of Marais throughout the proceedings. His crime seemed to lie lightly on him.

Laconic slaughter is very much a feature of South African life. The killings between tribe and tribe, faction and faction, con- tinue in the townships unabated by appeals from Mandela and Buthelezi. At work one of our black workers told how, in the course of a feud, he and his gang had ordered the black family of a rival faction out of their house before they burnt it down; the woman with her children left the house but was adamant that her husband was not inside; the house burnt down but it turned out that the husband was inside and was roasted to death. The black worker told this story in the manner of a schoolboy telling of a prank that had gone slightly wrong.

At the time of the Soweto uprisings in 1976, a foreign journalist remarked that for the first time in his life he had seen people who were so angry that they were not afraid to die. He implied a righteous anger in a grand cause. Today South Africans are prepared to die for the most trivial causes, and that is much more frightening. Recent- ly two white motorists killed each other in a gunfight after one had pulled out in front of the other; the cause for which they were willing to kill and to die was two seconds' delay at a road junction.

The standard explanation for all this is that apartheid has robbed South Africans of their humanity and made them brutal and callous: the blacks have been cor- rupted by their oppression and the whites by their guilt. This solemn theory, trotted out by every second political commentator, is complete nonsense. In black African countries to the north there is at least as much brutality between blacks as there is in South Africa. White South Africans feel as little guilt about apartheid as white Americans do about the genocide of the Red Indians. The relaxing of apartheid has been followed by more, not less, violence and brutality.

In the parts of South Africa where the good and the bad ways of the white man have scarcely reached, there is an unre- ported background of horror. While I was at a power station in the Transvaal, I came in once for tea to hear one of the super- visors, a beefy and avuncular ex- policeman, describing methods of inter- rogation he had used while conducting investigations in the rural areas. Over his cheese and tomato sandwich, he described in detail how he had partially suffocated and half-drowned the black suspects to extract information. I asked their crime. He said it was murder for muti. (Muti is the traditional healing magic used by the san- gomas, the witch-doctors). Various parts of the human body, especially of a child, are prized for muti. The favourite pieces include eyes, knees, elbows and testicles, and the selected children are usually about five years old. For 'good muti' it is neces- sary to remove these parts while the donor is alive. In the course of his police work, the genial supervisor had come across small corpses with bits missing. He justi- fied the rough interrogations by saying that it had upset him to see bodies of "little kids with their eyes and ball-bags cut out".

Having lived in both countries, I used to believe that life in the gentle England of today was natural for human beings and that life in violent South Africa was an aberration. Now I am inclined to believe the opposite, that the respect for life you find in England and a few other countries today, is unusual in human history and essentially unnatural. Caring about people outside a small circle of relatives and friends is not inherent in human nature.

A young colleague died tragically at a factory I worked for in England. Relatives, friends and workmates went to the funeral at noon in a small church. The mourners arranged themselves in layers of dimi- nishing sorrow. At the front of the church were the young wife and infant children, wracked with grief; in the next row were sobbing aunts and uncles; behind them close friends with sad expressions; but at the back of the church, where I was standing, the slight acquaintances were glancing at their watches, thinking that if the person got a move on they might have time to slip into the pub for a swift pint on the way back to work.

How many people do you know whose death would make you cry? For me the number is fewer than ten. I doubt if there are many people for whom the number would be more than 50. Our behaviour to people within this circle of tears is inhe- rent, part of our nature, but outisde it our behaviour is governed by external forces of culture, religion, art and law; and when we look to people outside our nation or tribe these forces become feeble or non- existent.

At least in Richards Bay I find that the white people here, including AWB suppor- ters, regard the death sentence on Eugene Marais as just (although he is unlikely to hang and could even be released in some future deal with the ANC to free 'political prisoners'). In a similar case in a Transvaal town where four white youths had savagely and nonchalantly killed an African woman, the white townsfolk were genuinely puz- zled when death sentences were passed — 'Maar sy was net 'n meid' Out she was just a black girl'). African tribesmen show the same puzzlement when foreign visitors reproach them for the slaughter of other tribes. Almost within living memory white Australians shot Aborigines for fun and pest-control.

Today black teenagers in the South African townships laugh while the bodies of the people they have ignited writhe in the flames. Not many centures ago honest English citizens watched with interest the condemned being disembowelled before having their hands cut off and their bodies quartered. All other mammals have an innate restraint against killing members of their own species. Man does not have this noble inhibition.

One reason for England's gentleness today is simple law-enforcement. You do not get gunfights between drunken motor- ists on Tottenham Court Road mainly because England, unlike South Africa, has effective laws controlling gun ownership and drunken driving. Another reason is that the tribes of England are very similar, making it easier to recognise each other more or less as fellow human beings. Yet a third reason is centuries of persuasion by religion and literature.

I have met a number of men who have killed, in war and in peace, and have been struck by the total absence of remorse felt. This, I believe, is usual among imprisoned murderers. Works such as Macbeth or Crime and Punishment are not so much psychological studies — in real life Lady Macbeth would not lose a wink of sleep over the murder of Duncan — as moral injunctions. If we do not naturally feel ashamed about killing people, we ought to, and it is part of the job of religion and art, bringing down a civilising Judaeo-Christian message of guilt, to make us feel so. As the background music in a cinema prompts us towards the required emotion in the film story, so the urgings of priests and play- wrights prompt us towards decent be- haviour to our fellow men and encourage us to feel badly when we have wronged them. In Africa these improving influences are few and feeble: It has often been said that the Christian message is too new and revolutionary to have yet had much influence among men. But for most of the world, including South Africa, the commandment from Mount Sinai over a thousand years earlier, 'Thou shalt not kill', is still novel, faintly heard and difficult to take very seriously.

Previous page

Previous page