Building Society Operations

BY FRED BENTLEY 1,HE history of building society development discloses a pattern

of alternating periods in which at one time there comes into Prominence the investment aspect (how to attract funds from the investing public) and at another time the mortgage aspect (how to stimulate demand for home loans).

In the last twelve months the maintenance of an adequate net investment inflow has proved to be the problem uppermost in the minds of building society directors and executives—and the prob- lem has been made more difficult of solution by the impact of Prevailing national financial conditions.

For many years the building sodiety contribution to total per- sonal savings has been noteworthy. The average annual increase in assets in the last five years is £161 million. In the year 1955 out of the estimated total personal savings of £962 million building society investors and borrowers provided some £260 million or 27 per cent. of the whole.

The increase in total assets of all societies in the last ten years from £876 million to £2,063 million appears impressive, but when, related to purchasing power does not record a vast forward move.' Those serving building societies would like to see an upsurge in total membership and particularly in the ranks of the small regular savers.

Whilst in the last decade share investors have increased from 2.0 millions to 2.7 millions, the number of depositors has fallen from 731,000 to 580,000. This fall would seem to signify that in general those who now invest in building societies have full confi- dence in the security of the share investment and desire to obtain the higher yield normally applicable to shares. Previously there was a greater disposition to take the lower deposit yield in order to obtain the priority of security attaching to investment in the deposit department.

There can be few more fervent supporters of the Government in its anti-inflationary measures than those who are engaged in the protnotion of thrift. The persistent fall in the purchasing power of the £ in post-war years has been a matter of the utmost concern to building societies and to their investing members. It is estimated that the average annual fall in purchasing power in each of the last ten years is in excess of 4 per cent. This means that the reward of thrift received by the investor in the form of interest has been more than offset annually by the loss of part of the capital value of the investment.

When the anti-inflationary restrictions upon credit were intro- duced in the spring of 1955 the gross investment inflow into building societies was running at a record level, but the with- drawals outflow was tending to increase, stimulated to some extent by the transfer of funds to the purchase of Stock Exchange securi- ties where a boom in 'equities' was in progress.

In succeeding months the continuance of the high rate of inflow of new investments demonstrated that there was no reduction in But as the year advanced the outflow of funds to meet with- drawal demand increased to such an extent as to make inevitable an appreciable reduction in the amount available for new loans on mortgage. For a time many societies found it necessary severely to curtail the acceptance of new applications for loans and at the present time most, if not all, societies are operating under some kind of quota regulations. It was the fulfilment of commitments entered into in the early months of the year which caused the total amount advanced in 1955 to reach the record of £392 million.

At a time like the present, when it is so desirable to encourage saving and when it is acknowledged that one of the best means of saving is by house purchase in the building society way, it is naturally a matter of regret to building -society officials that adequate funds are not available to meet the insistent demand, much of which conforms to the high standard of quality which is sought in the selection of mortgage securities.

Such adequate funds can only be secured by an increase in new investment inflow or a reduction in withdrawals—apart from those funds which are made available through instalment and final repayments of existing loans, which repayments provide an important contribution to new lending. In 1955 £294 million were received by societies by way of mortgage repayments and interest.

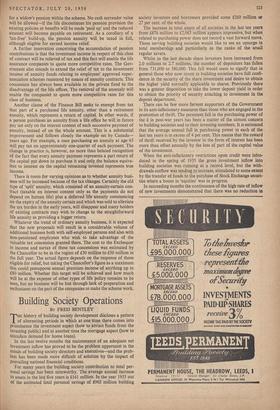

In present conditions the effect of the level of interest rates upon investment recipts and withdrawals is not easy to estimate. In July, 1955, there was a general increase of J (to 3 per cent.) in the paid-up share rate—the rate which is of the greatest influence in the attraction of new funds; the deposit rate is usually a little lower (now generally 2-1 per cent.) and the subscription share (or regular saving) rate a little higher (say 31 per cent.). These rates are all subject to the payment of income tax by the society. The July, 1955, increase appeared to be effective in stimulating inflow, although it is not possible to state what part of the improvement came from the attraction of the higher rate of interest and what part from a change of external conditions, e.g., the end of the boom in 'equities.'

Now, in July, 1956, the problem is, should there be a further general increase in rates, primarily for the investor and conse- quentially for the borrower? available substantial liquid funds. Adherence to a prudent policy in this respect has during the last twelve months further impelled societies to restrict lending. Whereas the Building Societies Asso- ciation imposes as a condition of membership the maintenance of a minimum liquidity ratio of 71 per cent. of total assets, most societies prefer a much higher margin; the percentage for all societies is now estimated to be about 15.

The severe fall in the market value of gilt-edged securities has created a problem for building societies in that societies have not generally been disposed to sell their investments and to record appreciable losses. They prefer naturally to hold until maturity dates or until the market improves. This experience of 'frozen liquidity' has led societies to hold larger balances at bank, to invest in Treasury bills and to select the shortest dated gilt-edged investments.

The higher yields now available on such investments have fortu- nately meant that the holding of substantial liquid resources has not resulted in an appreciable cut in the margin of surplus.

The rapid rate of growth over the last few years has, in the main, caused for building societies a lowering of the average percentage reserve ratio. The ideal set by the Association is 5 per cent., but most of the larger societies have in recent years, due to rapid growth, been unable to maintain the ideal. A reduction of the rate of growth which appears to be inevitable under existing general conditions will no doubt help many societies in the current year to build up their reserves.

The substantial reserves carried by most building societies in- spire—as they are intended to do—public confidence, but it is worthy of record that only on rare occasions and generally in abnormal circumstances has it been necessary to call upon reserves to meet losses.

The traditional promptitude with which building society borrowers honour their mortgage commitments is another of the bulwarks of public confidence. At the end of 1955 there were recorded by the Chief Registrar only 706 properties over twelve months in the possession of societies through default, with total amount owing of £777,000. There were at the time 1,996,000 mort- gages and total balances due on mortgage £1,749 million. These figures reflect the soundness of building society boards' lending policies and the care with which mortgage risks are selected.

The Chancellor has said that the monetary measures being taken in the national interest will hurt, and in many quarters pain is being felt and disruption experienced, but if the present value of the £ is pregerved, if not increased, then those associated with building societies will consider that the treatment has been worth taking.

Previous page

Previous page