LAND FOR THE JEWS

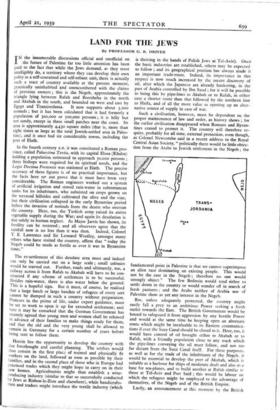

By PROFESSOR G. R. DRIVER I N the innumerable discussions official and unofficial on the future of Palestine far too little attention has been paid to the fact that while the Jews demand, as they most intelligibly do, a territory where they can develop their own polity as a self-contained and self-reliant unit, there is actually such a tract of country available at the present moment, practically uninhabited and unencumbered with the claims of previous owners ; this is the Negeb, approximately the triangle lying between Rafah and Beersheba in the north and Akabah in the south, and bounded on west and east by Egypt and Transjordania. It now supports about 5,000 nomads ; but it has been calculated that it had formerly a population of 300,000 or 500,000 persons ; it is hilly but not sandy, except in three small patches near the coast. Its area is approximately 4,430 square miles (that is, more than eight times as large as the total Jewish-settled area in Pales- tine), and it once had six considerable towns, including the port of Elath.

In the fourth century an. it was constituted a Roman pro- vince, called Palaestina Tertia, with its capital Elusa (Khalsa) holding a population estimated to approach 50,000 persons ; three bishops were required for its spiritual needs, and the Legio Decima Fretensis was stationed at Elath. The precise accuracy of these figures is of no practical importance, but the facts here set out prove that it must have been very considerable. The Roman engineers worked out a system of artificial irrigation and stored rain-water in subterranean tanks for its inhabitants, who subsisted on crops grown on the terraced hillsides and cultivated the olive and the vine, but their civilisation collapsed in the early Byzantine period before the invasion of nomads from the desert who overran the country. Here, too, the Turkish army raised its entire vegetable supply during the War; and again its desolation is due solely to human neglect. As Major Jarvis has shown, its fertility can be restored ; and all observers agree that the rainfall now is no less than it was then. Indeed, Colonel T. E. Lawrence and Sir Leonard Woolley, amongst many others who have visited the country, affirm that "today the Negeb could be made as fertile as ever it was in Byzantine times."

The re-settlement of this desolate area must and indeed can only be carried out on a large scale ; small colonies would be starved out. Further, roads and ultimately, too, a railway across it from Rafah to Akabah will have to be con- structed if any scheme of settlement is to be successful. Besides rain-water, there is also water below the ground. This is a hopeful sign. But it must, of course, be realised that a large batch or large batches of refugees of every sort cannot be dumped in such a country without preparation. Pioneers in the prime of life, under expert guidance, must be set to work to open it up for extended settlement; and here it may be remarked that the German Government has recently agreed that young men and women shall be released in advance of their families to make things ready for them, and that the old and the very young shall be allowed to remain in Germany for a certain number of years before being sent to follow them.

Herein lies the opportunity to develop the country with due forethought and careful planning The settlers would thus consist in the first place of trained and physically fit workers on the land, followed as soon as possible by their families, and in the second place of those who in Europe had practised trades which they might hope to carry on in their new homes. Agriculturists might thus establish a wine- producing industry (similar to that so successfully conducted by Jews at Rishon-le-Zion and elsewhere), while handicrafts- men and traders might introduce the textile industry (which is thriving in the hands of Polish Jews at Tel-Aviv). Once the basic industries are established, others may be expected to follow ; and its geographical position has always made it an important trade-route. Indeed, its importance in this respect is now much increased by the recent discovery of oil, after which the Japanese are already hankering, in the part of Arabia controlled by Ibn Saud ; for it will be possible to bring this by pipe-lines to Akabah or to Rafah, in either case a shorter route than that followed by the northern line to Haifa, and of all the more value as opening up an alter- native source of supply in case of war.

Such a civilisation, however, must be dependent on the proper maintenance of law and order, as history shows ; for the earlier civilisation disappeared when Romans and Byzan- tines ceased to protect it. The country will therefore re- quire, probably for all time, external protection, even though, as Colonel Newcombe said in a recent address to the Royal Central Asian Society, "politically there would be little objec- tion from the Arabs to Jewish settlement in the Negeb ; the fundamental point in Palestine is that we cannot superimpose an alien race dominating an existing people. This would not be the case in the Negeb ; therefore no one would strongly object." The few Bedouin would tend either to settle down in the country or would wander off in search of fresh pastures ; and the Arabs neither of Arabia nor of Palestine show as yet any interest in the Negeb.

But, unless adequately protected, the country might easily fall a prey to an ambitious Power seeking a fresh outlet towards the East. The British Government would be bound to safeguard it from aggression by any hostile Power and would at the same time be keeping open an alternate route which might be invaluable to its Eastern communica- tions if ever the Suez Canal should be closed to it. Here, too, it would have control of oil brought either to Akabah or to Rafah, with a friendly population close to any track which the pipe-lines conveying the oil must follow, and not too far distant from the Suez Canal itself. For these purposes, as well as for the trade of the inhabitants of the Negeb, it would be essential to develop the port of Akabah, which is suitable as a harbour for ships of moderate draft and also as a base for sea-planes, and to build another at Rafah similar tc those at Tel-Aviv and Port Said ; this would be labour on which the refugees might be employed to the advantage of themselves, of the Negeb and of the British Empire.

Lastly, an announcement at this moment by the British Government that it intended to put an end to the immigra- tion of Jews into Palestine would at once appease much Arab hostility both overt and latent, particularly at a time when the Italian Government has roused Moslem anger by the Albanian invasion, while the offer of the Negeb to the Jews would be welcomed by very many of them as the best possible settlement of the Jewish question in the present circumstances. If, too, the Negeb were populated to its full capacity with Jewish settlers, it would be able to maintain itself against any neighbours if it were admitted to the British Commonwealth of nations, and no other country would be able to use it as a base against Palestine or Egypt.

There is ample evidence that such a scheme is econo- mically feasible as well as strategically desirable. Money, however, would be required. This might be found partly by the formation of a chartered company (supported pre- sumably for the most part, if not entirely, by Jewish funds) for the development of the country, and partly by the British Government for the carrying out of such strategical works as might be thought desirable.

Previous page

Previous page