ADVICE TO THE TREASURY OR LORD RADCLIFFE

By NICHOLAS DAVENPORT FRANKLY, I had no intention of

• referring to the gilt-edged market

\ • , again for some considerable time—: it is becoming a bore—but I cannot

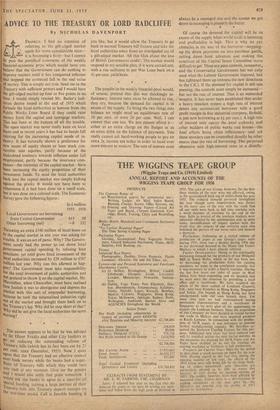

let pass the pontifical comments of the weekly linancial-economic press which would have you believe that the Government can do nothing to Improve matters until it has conquered inflation and stopped the continual fall in the real value of money. This is simply not true. Send me to the Treasury with sufficient powers and I would have the gilt-edged market up four or five points in no lime. I would simply rescind Mr. Butler's ludi- crous decree issued at the end of 1955 which forbade the local authorities to borrow from the public Works Loan Board if they could raise Money from the capital and mortgage markets. This has been at the bottom of all the trouble. The open market was never really keen on local loans and in recent years it has had its hands full catering for the increasing capital needs of in- dustry. It has naturally shown a preference for new issues of equity shares or loan stock con- vertible into equities, partly because of the undoubted tendency towards inflation under full employment, partly because the insurance corn- Panies—the mainstay of the capital market—have been increasing the equity proportion of their mvestment funds. To send the local authorities hack into the capital market was simply kicking against the pricks. It would not have been so calamitous if it had been done on a small scale, but it was done on a colossal scale. The Economic Survey gave the following figures : In £ million 1955 1956 Local Government net borrowing from Central Government .. 413 88 Other borrowing (net) —8 332

Throwing an extra £340 million of local loans on to the capital market in one year was asking for trouble. It was an act of panic. Why? The Govern- ment surely had the power to cut down local 80vernment capital spending by refusing loan sanctions; yet total gross fixed investment of the local authorities increased by £29 million to £567 million last year. Why was this allowed to hap- Pen? The Government must take responsibility for the total investment of public authorities and not pretend to throw it on the capital market. Mr. Macmillan, when Chancellor, must have realised 110W foolish it was to disorganise and depress the Market with this sort of unpopular borrowing, because he look the nationalised industries right out of the market and brought them back on to the Treasury's lap. Why did he stop short at that? Why did he not give the local authorities the same nursing?

The answer appears to be that he was advised uy Sir Oliver Franks and other City bankers to F.° on reducing the outstanding volume of reasury bills (which has in fact been cut by 25 Per cent. since December, 1955). Now I quite 4gree that the Treasury had no effective control uvcr bank money while the banks had a super- fluity of Treasury bills which they could turn 1M0 cash at any moment. Give me the powers and I wduld also settle that point tomorrow. I Would ask the banks to agree to a once-for-all 'Pedal funding, turning a large portion of their I reasury bills into Treasury deposit receipts on thc war-time model, Call it forcible funding if you like, but it would allow the Treasury to go back to normal Treasury bill finance and take the local authorities away from an overloaded ass of a gilt-edged market. All this blah about the loss of British Government credit! The market would respond to my sensible plan, if it were carried out, with a rise sufficient to put War Loan back on a 4,, per cent. yield basis.

The pundits in the weekly financial press would, of course, pretend that this was shockingly in- flationary. Interest rates must be allowed to rise, they cry, because the demand for capital is in excess cf the supply. To bring the two things into balance we might need an equilibrium rate of 10 per cent, or even 20 per cent. Well, I can answer that one too. We just cannot afford it— either as an extra charge on the Budget or as an extra debit On the balance of payments. You really. cannot ask hard-working people to pay an extra 2s. income tax today in order to hand over more interest to rentiers: The rate of interest must

always be a managed one and the sooner we get down to managing it properly the better.

Of course the demand for capital will be fix excess of the supply when world trade is boomirm and profitability is high. That is why we put obstacles in the way of the borrower—stepping- up the down payments on hire-purchase goods, cutting down bank advances and making the sanctions of the Capital Issues Committee more difficult to get. These are pure controls, remember,. and the Conservative Government has not only used what the Labour Government imposed, but has tightened them up (witness the new directions to the CIC). If the, demand for capital is still to pressing, the controls must simply be increased— but not the rate of interest. That is an outmoded weapon. It has, never been established that under a heavy taxation system a high rate of interest deters any commercial borrower with a good profit margin (a tine industrial company, Birtield, is just now borrowing at 61 per cent.). A high rate of interest only upsets the local authority and other builders of public works and houses—the final effects being often inflationary—and yet these spenders can be controlled directly by other means than the rate of borrowing. This perpetual obsession with high-interest rates as a disinfla- tionary weapon has pushed the Treasury into an absurd contradiction in monetary technique and completely demoralised the gilt-edged market. It is time to end this muddle. The rate of interest has got to be managed properly and the demand for capital effectively controlled. If the Treasury does not mend its ways this country, living pre- cariously on its foreign trade, will find itself before long as uncreditworthy as a South Ameri- can republic.

Previous page

Previous page