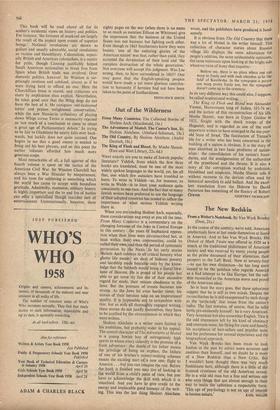

Out of the Wilderness

From Many Countries. The Collected Stories of Sholem Asch. (Macdonald, 16s.) The Adventures of Mottel: The Cantor's Son. By

Deutsch, 18s.)

The King of Flesh and Blood. By Moshe Shamir. (East and West Library, 22s. 6d.) WHAT exactly are you to make of Jewish popular literature? Yiddish, from which the first three books are translated, must be one of the most widely spoken languages in the world, yet, for all that, one which few outsiders have troubled to learn. To write in Yiddish—as, for instance, to write in Welsh—is to limit your audience quite consciously to one race. And the fact that so many Jewish writers have preferred to use the language of 'their adopted countries has tended to inflate the importance of what serious Yiddish writing there is.

When you are reading Sholem Asch, especially, these considerations nag away at you all the time. From Many Countries is a commentary on the changing fortunes of the Jews in Central Europe in this century : , the years bf haphazard oppres- sion when their lives were circumscribed but, at least within their, own communities, could be callecitheir own,and then the period of systematic ,persecution by the Nazis. in his early stories Sholem Asch cohVeys in all critical honesty what ghetto life meant : six days of hideous poverty and hardship made bearable' only by the know- ledge that the Sabbath would bring a literal fore- taste of Heaven. He is proud of his people but able to get some sly fun out of their excessive regard for study, their minute obedience to the laws. But the pressure of events becomes too strong. As the Jews hit even harder times, his stories of their heroism take on an inspirational quality. It is impossible not to sympathise with this; but as with all thoroughly engaged writing, these stories do not justify themselves, they have to be justified by the circumstances in which they were written.

Sholom Aleichem is a writer more limited in his ambitions, but probably wider in his appeal. The central character of The Adventures of Mottel is a young Jewish boy of outrageously high spirits to whom every calamity is the promise of a fresh adventure : the death of his father means the privilege of being an orphan; the failure of one of his brother's money-making schemes means the exciting start of a new one; flight to America . . . but you can imagine the rest. Before the book is finished you may tire of looking at the world from a child's point of view, but you have to acknowledge the skill with which it is visualised. And you have to give credit to the energy and implacable good humour of the Writ- ing. This was the last thing Sholom Aleichem wrote, and the publishers have produced it hand- somely.

It is obvious from The Old Country that there was a lot of Mottel in the writer himself. This collection of character stories about Russian village life displays the same admiration for people's oddities, the same undauntable optimism, the same insistence upon looking at the bright side whatever twist of irony that requires :

Believe me, there is no place where one can weep so freely and with such abandon as 'in 'the field' of Kasrilevka. In the synagogue a person can weep pretty freely too, but the synagogue doesn't come up to the cemetery.

In its very different way this could also, I suppose, be called inspirational writing, The King of Flesh and Blood was Alexander Yannai, Hasmonwan king of Judtea, 103-76 Etc; and the author of this reconstruction of his life, Moshe Shamir, was born in Upper Galilee in 1921, fought with the shock troops of the Haganah, and is regarded as one of the most important writers to have emerged in the ten-year- old State of Israel. The fascination of Yannai's life for a writer who has been concerned in the building of a nation is obvious. It is the story of man absorbed in two basic problems of nation- alism : the consolidation of his nation's boun- daries, and the amalgamation of the authorities of the priesthood and the throne. It is also a story of the corruption worked by ambition, bloodshed and suspicion. Moshe Shamir tells it without recourse to the devices often used by historical novelists to add ballast. And the excel- lent translation from the Hebrew by David Patterson has something of the fluency of Robert

Previous page

Previous page