A NONAGENARIAN ATOM BOMB

Andrew Robinson on

India's most original and controversial thinker

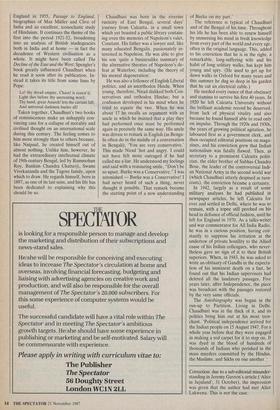

I LAST met Nirad Chaudhuri, then a few months short of his 90th birthday, on 15 August, which happened to be the 40th anniversary of India's Independence. He did not once mention the date but spoke animatedly about his book Thy Hand, Great Anarch!, published this month, jumping up from time to time to extract some particularly pungent passage from the pile of proofs sent to hiin by the publisher, which ran to nearly a thousand pages. So, as we parted at the gate of one of those solid Victorian houses in North Oxford where he has come to rest, I mentioned the coincidence myself. No response; it was obvious that he reckoned that his feelings were fully expressed in the book, and added that I should prepare myself, as a probably degenerate modern Englishman, for a shock. 'I have thrown an atom bomb,' he said gleefully. `You can throw a brick.'

Some time later, when I had almost finished his magnum opus, I wrote to him querying a few points and added that the book was immensely interesting, even though I could not agree with all of it. 'Your reservation was really not needed,' he reprimanded me by return. 'An author would be very unreasonable if he expected his readers to agree with all that he has to say, even with anything at all. I myself would in that case think that the book was not worth the trouble of writing.'

As his friend, the veteran journalist Khushwant Singh (who is no mean con- troversialist himself), has pointed out, `Nirad Chaudhuri is not a modest man: he has much to be immodest about,' nor can he resist provoking people, especially the westernised elite of India he knows so well.

He began doing this on a grand scale in 1951 with the publication of The Auto- biography of an Unknown Indian, which quickly became a classic: Churchill thought it one of the best books he had read, and V.S. Naipaul 'maybe the one great book to have come out of the Indo-English encoun- ter'. Its dedication read: 'To the memory of the British Empire in India which conferred subjecthood on us but withheld citizenship; to which yet every one of us threw out the challenge: "Civis Britannicus sum" because all that was good and living within us was made, shaped and quickened by the same British rule.' Newly indepen- dent India seemed not to concur, or, in Khushwant Singh's words, 'The wogs took the bait and having only read the dedica- tion sent up a howl of protest.' The howl subsequently became a sneer, reinforced by the current anti-imperialist fashion, and so it has remained; only last month, in a lament for the idealism which has so rapidly declined in India during 1987, the editor of The Illustrated Weekly of India took a ritual swipe at Chaudhuri as 'our senile anglophile'.

The second volume of his autobiography follows his account of his first visit to England in 1955, Passage to England, biographies of Max Willer and Clive of India and an excellent, iconoclastic study of Hinduism. It continues the theme of the first into the period 1921-52, broadening into an analysis of British inadequacies both in India and at home — in fact the decadence of Western civilisation as a whole. It might have been called The Decline of the East and the West; Spengler's book greatly influenced Chaudhuri when he read it soon after its publication. In- stead it takes its title from some lines by Pope:

Lo! thy dread empire, Chaos! is restor'd; Light dies before thy uncreating word; Thy hand, great Anarch! lets the curtain fall; And universal darkness buries all!

Taken together, Chaudhuri's two books of reminiscences make an unhappily con- vincing case for a collapse of morality and civilised thought on an international scale during this century. The feeling comes to him more strongly than to others because, like Naipaul, he created himself out of almost nothing. Unlike him, however, he had the extraordinary intellectual climate of 19th-century Bengal, led by Rammohun Roy, Bankim Chandra Chatterji, Swami Vivekananda and the Tagore family, upon which to draw. He regards himself, born in 1897, as one of its last sons, and his life has been dedicated to explaining why, this should be so. Chaudhuri was born in the riverine rusticity of East Bengal, several days' journey from Calcutta, in a small town which yet boasted a public library contain- ing even the memoirs of Napoleon's valet, Constant. His father was a lawyer and, like many educated Bengalis, passionately in- terested in Napoleon. He was able to give his son 'quite a businesslike summary of the alternative theories of Napoleon's de- feat at Waterloo, including the theory of his mental degeneration'.

He was also a follower of English Liberal politics, and an unorthodox Hindu. When young, therefore, Nirad disliked both Con- servatives and orthodox Hindus; but a confusion developed in his mind when he tried to equate the two. When he was about 17 he recalls an argument with an uncle in which he insisted that a play they had performed once must be performed again in precisely the same way. His uncle was driven to remark in English (as Benga- lis often do in the middle of a conversation in Bengali), 'You are very conservative.' This made Nirad 'hot and angry. I could not have felt more outraged if he had called me a liar. He understood my feelings and said with a reassuring smile, "Don't be so upset. Burke was a Conservative." I was astonished — Burke was a Conservative! I had never heard of such a thing, never thought it possible. That remark became the starting point of a new understanding of Burke on my part.'

The reference is typical of Chaudhuri and of the Bengal of his time. Throughout his life he has been able to renew himself by immersing his mind in fresh knowledge from every part of the world and every age, often in the original language. This, added to his conviction that he is in the right, a remarkable, long-suffering wife and his habit of long solitary walks, has kept him young and spry. (He used to get up for dawn walks in Oxford for many years and this summer he dug so deep in his garden that he cut an electrical cable.) He needed every ounce of that obstinacy and stamina to survive his first 40 years. In 1920 he left Calcutta University without the brilliant academic record he deserved, from lack of physical vitality and also because he found himself able to read only on impulse. Through the 1920s and 1930s, the years of growing political agitation, he laboured first as a government clerk, and then occupied editorial positions on maga- zines, and his conviction grew that Indian nationalism was fatally flawed. Then, as secretary to a prominent Calcutta politi- cian, the elder brother of Subhas Chandra Bose, the leader of the controversial Indi- an National Army in the second world war (which Chaudhuri utterly despised as turn- coats), the conviction became a certainty. In 1942, largely as a result of some military analyses he had published in newspaper articles, he left Calcutta for ever and settled in Delhi, where he was to remain, with a topee still perched on his head in defiance of official fashion, until he left for England in 1970. As a talks-writer and war commentator for All India Radio, he was in a curious position, having con- stantly to suppress his irritation at the undertow of private hostility to the Allied cause of his Indian colleagues, who never- theless gave no sign of it to their British superiors. When, in 1943, he was asked to write an obituary of Gandhi in the expecta- tion of his imminent death on a fast, he found out that his Indian supervisors had deleted all the laudatory passages. Five years later, after Independence, the piece was broadcast with the passages restored by the very same officials.

The Autobiography was begun in the run-up to Partition. Living in Delhi, Chaudhuri was in the thick of it, and its politics bring him out at his most tren- chant. 'Political independence arrived for the Indian people on 15 August 1947. For a whole year before that they were engaged in making a red carpet for it to step on. It was dyed in the blood of hundreds of thousands of Indians who perished in the mass murders committed by the Hindus, the Muslims, and Sikhs on one another .'

Previous page

Previous page