Red-faced men who did well out of the war

Max Egremont

THE COUNTRYSIDE AT WAR 1914-1918

by Caroline Dakers

Constable, £12.95

The Countryside at War is not an exciting title. It made me think of an entry for one of those New Statesman competi- tions that attracted attention when the magazine was still successful, some ten or 20 years ago: perhaps for the book least likely to sell in the pre-Christmas rush. This is unfortunate because Caroline Dak- ers has written a good study of an aspect of the First War. At times she has used her material so well that the reader is taken directly into the sadness ipf those years, particularly when she describes the terrible losses suffered by almost all the families mentioned in these pages.

Having had access to the Mells and Stanway papers, she writes in detail about the Homers and Wemysses and their rela- tions, the Adeanes of Babraham and the Wyndhams of Clouds. We are back in the world of the Souls, or the children of the Souls,,observed this time from the point of view of the estate accountant as well as the social historian. For Caroline Dakers shows the financial pressures on these families as they tried to run not only their own large houses but support hundreds of dependent pensioners and estate workers who lived in rent-free cottages on the various farms and in the villages. This was not a problem which drew much sympathy then, nor does it now; certainly the Hor- ners and Wemysses were not exactly poor. But between 1873 and 1909 the depressed condition of agriculture had driven the farm rents on the Wemysses' Gloucester- shire estate of Stanway down by 48 per cent, and this at a time when other costs were rising. When war was declared in 1914, 250 country houses were immediate- ly offered to the government for use as hospitals or convalescent homes by owners desperate to get them at least temporarily off their hands.

If the aristocracy quaked before the spectre of increased death duties and Lloyd George's Undeveloped Land Duty, other inhabitants fared worse. Almost all agri- cultural labourers lived below the poverty line in 1914. Families like the Wemysses and the Homers were generally fair in their treatment of employees but other farmers were often harsh. Lack of prospects led to an increased exodus to the cities and many of those who stayed on the land took part in the strikes which became a feature of farming life. With the war came the added danger of the Zeppelin raids on southern England. It is not surprising that many farm workers rushed to enlist in Kitchen- er's great recruiting campaign.

This is different to the pre-war idyll depicted in the thoughts and writings of another category of country people: those who spent time there but did not depend on the place for their livelihoods. The early years of the century had seen the rise of pastoral sentimentality, symbolised by the Arts & Crafts movement, the Georgian poets and the magazine Country Life. This was the world to which Siegfried Sassoon looked back in Memoirs of a Foxhunting Man, the world of lush gardens laid out by Lutyens and Gertrude Jekyll for the bank- ers and stockbrokers of Surrey and Kent, a world against which Auden and Spender would rebel to praise the Oxford gas works and write odes to pylons.

In addition there was the immense popu- larity of field sports, of hunting and shoot- ing. For many officers a few days with the Quom or the Pytchley seemed a perfect break from the trenches. This sentiment was not shared by the Bloomsbury Group's collection of conscientious objectors, forced to work on the land, whose chaotic activities at Charleston and Garsington are deftly recounted by Caroline Dakers, a contrast to the military efficiency with which Kipling ran his agricultural opera- tions at Batemans.

Farmers did well out of the war. This country, an importer of four fifths of its wheat and half its meat in 1914, was forced by the U-boat blockade to grow more. Guaranteed prices, new machinery, women and German prisoners made up for the lack of regular workers, most of whom were at the front. In the trenches, the longing for green fields grew. Soon the poets became as touched by the beauties of Picardy as they had been by those of Kent or Gloucestershire, a further reminder that the two sides were destroying the Europe each was pledged to save. At home, in the south of England, the guns could be heard from across the Channel as the list of names lengthened for each parish's memo- rial book of remembrance. Caroline Dak- ers quotes from letters to describe a series of personal tragedies, in particular the deaths of the heirs of Stanway, Mells and Clouds. She uses the diaries of a country vicar and a schoolmaster to show the effect of the war on village life.

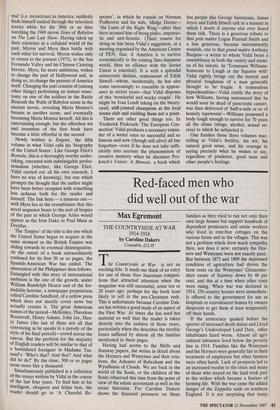

Such accounts are still harrowing, even some 70 years later. Inevitably we hear mostly of the literate, of the families whose papers have been preserved in cupboards or muniment rooms century after century: little of Kipling's 'mere uncounted folk' who have left few records. Nevertheless I commend The Countryside at War for its careful research and tone of quiet melan- choly that is appropriate to its subject. The illustrations are excellent, particularly the photograph of Lord Wemyss as a baby, sharing his pram with a bulldog apparently cowed by the great force of the infant's authority.

Previous page

Previous page