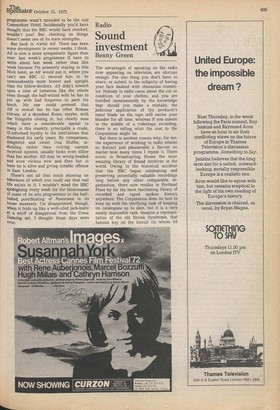

Radio

Sound investment

Benny Green

The advantages of speaking on the radio over appearing on television are obvious enough. For one thing you don't have to shave, or submit to the indignity of having your face daubed with obnoxious cosmetics. Nobody in radio cares about the cut or condition of your clothes, and you are fortified immeasurably by the knowledge that should you make a mistake, the judicious application of the producer's razor blade on the tape will excise your blunder for all time, whereas if you sneeze in the middle of a videotape recording, there is no telling what the cost to the Corporation might be.

But there is another reason why, for me, the experience of working in radio retains so distinct and pleasurable a flavour no matter how many times I repeat it. There exists in Broadcasting House the most amazing library of Sound Archives in the world. Owing to the historical accident that the BBC began cataloguing and preserving potentially valuable recordings long before any other comparable organisation, there now resides in Portland Place by far the most fascinating library of recorded and taped spoken history anywhere. The Corporation does its best to keep up with the terrifying task of keeping its catalogues up to date, but it is a very nearly impossible task. Imagine a representation of the old Shrink Syndrome, that famous boy on the biscuit tin whose lid shows a boy on a biscuit tin whose lid . . . now conjure up the diametric reverse of that syndrome, seven cars transported from the factory by one of those huge carcarrying lorries, which itself was once transported, with six other huge carcarrying lorries from the factory by an even larger lorry, which itself was once transported, with six other even larger lorries . . . dwell for a moment on that particular little nightmare, and you begin to get some idea of the geometrical progression of the problem facing the BBC's sound archivists. In one of its several catalogues, the years from 18891919 are covered in eight pages, 1961 by two pages, 1969 by sixty-one pages.

By far the most valuable lessons which the Sound Archives can teach us is that because of the unnatural pace of technological progress in this century, we have acquired a false perspective which has led us into the error that all history apart from our own must necessarily be irretrievably remote. But the archives correct this impression time and again, in the most spectacular way. Only seven years ago, for instance, a man was interviewed about his friendship with the last surviving officer who fought at the Battle of Waterloo, and later that same year another speaker reminisced about the Matabele rising against the British in 1895. That is one kind of link with the past, where the talker is long enough in the tooth to give an eye-witness account of an event of stupefying antiquity. There is also the other, more direct kind, where the flavour of a remote event is preserved for all time by a recording made at the time of the said event. In this category comes the voice of William Ewart Gladstone congratulating Edison on the invention of the phonograph (1889), Phineas T. Barnum thanking the British for supporting the Greatest Show On Earth (1890), and, on July 30 of that same year, Florence Nightingale delivering a sixty-second message to posterity.

Of course there is a preponderance of the ponderous, especially those interminable items of cotton wool from the panjandrums of a vanished world stage, and it will come as no surprise to students of modern British history to learn that probably the most asinine of all these vote-cadging proclamations comes from that beloved knockabout comic, the Lossiemouth Loosemouth, the Unknowing Prime Minister James Ramsay MacDonald, who on August 28, 1931, less than fortyeight hours after announcing he had decided to "form a government of individuals whose task would be confined to dealing with the financial emergency," actually had the effrontery to tell BBC listeners that "politicians should be careful what they say."

Limiting my researches to the "H to M" section, I see that General Sir Ian Hamilton was summoned to Osborne House after Majuba to give an account to the Queen; that in 1943 Stephen Leacock spoke for 7 minutes 25 seconds about his teaching experiences; that in a 1959 talk L. S. Lowry explained why his favourite painter was Rossetti; and that in the previous year Miss Jayne Mansfield had revealed her longing to play a female Hamlet. Finally there is the supreme piquancy of Mongomery, who takes 43.57 to discuss his own memoirs but only 1.25 to explain the extent of Eisenhower's grasp of strategy.

In addition the archive catalogues bulge with the kind of calculated quaintness for which the BBC has become world-famous: an interview with Britain's first lady bank manager; a cellist who goes into her garden at night to accompany the local nightlingales; how to kill a wild duck with a boomerang; a talk with the TV .viewing champion of England, a housewife who even watches the test card; Sir Shane Leslie claiming in 1937 to have received supernatural instructions not to board a train which duly crashed to disaster, which sounds suspiciously like a plagiarism of Beerbohm's story, A. V. Laider '; a gentleman from Hampshire describing a ghost encountered, naturally, on a dark, foggy night; Mrs Moonie Horton of 'The Dover Castle,' Weymouth St, WI, describing the life of a public house landlady; interview with the owner of a tame sparrow, and so on. The longest item I could find was Harold Macmillan's 57.20 in an address to the South African parliament; the shortest Robertson Hare's 'Oh Calamity,' in exactly two seconds. Earlier this year an item of Mine went into BBC archives for the first time. It was to do with the Marx Brothers, and in view of the inexhaustible riches of the existing catalogues, it is no wonder that I took my entry into the lists as the professional accolade. See you soon, Ramsay old pal.

Previous page

Previous page