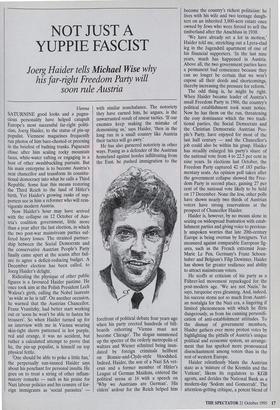

NOT JUST A YUPPIE FASCIST

Joerg Haider tells Michael Wise why

his far-right Freedom Party will soon rule Austria

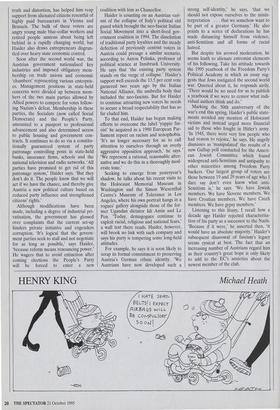

Vienna SATURNINE good looks and a pugna- cious personality have helped catapult Europe's most successful far-right politi- cian, Joerg Haider, to the status of pin-up populist. Viennese magazines frequently run photos of him bare-chested or preening in the briefest of bathing trunks. Paparazzi chase after him scaling rocky mountain faces, white-water rafting or engaging in a host of other swashbuckling pursuits. But his main enterprise is to become Austria's next chancellor and transform its constitu- tional democracy into what he calls a Third Republic. Some fear this means restoring the Third Reich to the land of Hitler's birth. Yet Haider's growing ranks of sup- porters see in him a reformer who will rein- vigorate modern Austria. Now Haider's hour may have arrived with the collapse on 12 October of Aus- tria's coalition government, little more than a year after the last election, in which the two post-war mainstream parties suf- fered heavy losses. The strained partner- ship between the Social Democrats and the conservative Austrian People's Party finally came apart at the seams after fail- ure to agree a deficit-reducing budget. A December election has been called, to Joerg Haider's delight. Ridiculing the physique of other public figures is a favoured Haider pastime. He once took aim at the Polish President Lech Walesa's girth, calling the Nobel laureate `as wide as he is tall'. On another occasion, he warned that the Austrian Chancellor, Franz Vranitzky, had better start working out or 'soon he won't be able to fasten his trousers'. So when Haider turned up for an interview with me in Vienna wearing skin-tight shorts patterned in hot purple, red and orange, it was no accident, but rather a calculated attempt to prove that he, the pin-up populist, is himself on top physical fettle.

`One should be able to poke a little fun,' the perpetually sun-tanned Haider says about his penchant for personal insults. He goes on to treat a string of other inflam- matory remarks — such as his praise for Nazi labour policies and his censure of for- eign immigrants as 'social parasites' — with similar nonchalance. The notoriety they have earned him, he argues, is the unwarranted result of smear tactics. 'If our enemies keep making the mistake of demonising us,' says Haider, 'then in the long run in a small country like Austria their tactics will go awry.'

He has also garnered notoriety in other ways. Posing as a defender of the Austrian homeland against hordes infliltrating from the East, he pushed immigration to the forefront of political debate four years ago when his party erected hundreds of bill- boards exhorting 'Vienna must not become Chicago'. The slogan summoned up the spectre of the orderly metropolis of waltzes and Wiener schnitzel being inun- dated by foreign criminals hellbent on Bonnie-and-Clyde-style bloodshed. Indeed, Haider, the son of a Nazi SA vet- eran and a former member of Hitler's League of German Maidens, entered the political arena at 16 with a speech on `Why we Austrians are German'. His elders' ardour for the Reich helped him become the country's richest politician: he lives with his wife and two teenage daugh- ters on an inherited 3,800-acre estate once owned by Jews who were forced to sell the timberland after the Anschluss in 1938.

`We have already set a lot in motion,' Haider told me, stretching out a Lycra-clad leg in the Jugendstil apartment of one of his financial supporters. 'In the last nine years, much has happened in Austria. Above all, the two government parties have a permanent bad conscience because they can no longer be certain that we won't expose all their deeds and shortcomings, thereby increasing the pressure for reform.'

The odd thing is, he might be right. When Haider became leader of Austria's small Freedom Party in 1986, the country's political establishment took scant notice. Now he has them on the run, threatening the cosy dominance which the two tradi- tional parties, the Social Democrats and the Christian Democratic Austrian Peo- ple's Party, have enjoyed for most of the last half century — and the Chancellor's job could also be within his grasp. Haider has steadily enlarged his party's share of the national vote from 4 to 22.5 per cent in nine years. In elections last October, the Freedom Party captured 42 of 183 parlia- mentary seats. An opinion poll taken after the government collapse showed the Free- dom Party in second place, gaining 27 per cent of the national vote likely to be held on 17 December. None the less, other polls have shown nearly two thirds of Austrian voters have strong reservations at the prospect of Chancellor Haider.

Haider is, however, by no means alone in seizing on widespread frustration with estab- lishment parties and giving voice to previous- ly unspoken worries that late 20th-century Europe is being overrun by foreigners. Yet measured against comparable European fig- ures, such as the French extremist Jean- Marie Le Pen, Germany's Franz Schoen- huber and Belgium's Filip Dewinter, Haider has shown far greater resilience and ability to attract mainstream voters.

He scoffs at criticism of his party as a Fiihrer-led movement repackaged for the post-modern age. 'We are not Nazis,' he says, turquoise eyes gleaming. And, indeed, his success stems not so much from Austri- an nostalgia for the Nazi era, a lingering if limited phenomenon with which he flirts dangerously, as from his cunning personifi- cation of anti-establishment attitudes. To the dismay of government members, Haider gathers ever more protest votes by highlighting the pitfalls of Austria's unique political and economic system, an arrange- ment that has sparked more pronounced disenchantment among voters than in the rest of western Europe.

Haider relentlessly blasts the Austrian state as a 'mixture of the Kremlin and the Vatican', likens its regulators to KGB agents, and derides the National Bank as a modern-day 'Sodom and Gomorrah'. The attention-getting critique, a potent blend of truth and distortion, has helped him reap support from alienated citizens resentful of highly paid bureaucrats in Vienna and Brussels. The bulk of these voters are angry young male blue-collar workers and retired people anxious about being left behind in a rapidly changing world, but Haider also draws entrepreneurs disgrun- tled over heavy state economic control.

Soon after the second world war, the Austrian government nationalised key industries and imposed obligatory mem- bership on trade unions and economic `chambers' representing various enterpris- es. Management positions in state-held concerns were divided up between mem- bers of the two main parties allowed by Allied powers to compete for votes follow- ing Nazism's defeat. Membership in these parties, the Socialists (now called Social Democrats) and the People's Party, amounted to a passport to professional advancement and also determined access to public housing and government con- tracts. It continues to do so via a constitu- tionally guaranteed system of party patronage controlling posts in state-held banks, insurance firms, schools and the national television and radio networks. 'All parties have promised to get rid of this patronage system,' Haider says. 'But they don't do it. The people know that we will act if we have the chance, and thereby give Austria a new political culture based on reduced party influence and strengthened citizens' rights.'

Although modifications have been made, including a degree of industrial pri- vatisation, the government has glossed over complaints that the current set-up hinders private initiative and engenders corruption. 'It's logical that the govern- ment parties seek to stall and not negotiate for as long as possible,' says Haider, `because reform means renouncing power.' He wagers that to avoid extinction after coming elections the People's Party will be forced to enter a new coalition with him as Chancellor.

Haider is counting on an Austrian vari- ant of the collapse of Italy's political old guard which brought the neo-fascist Italian Social Movement into a short-lived gov- ernment coalition in 1994. The dissolution of traditional party loyalties and the steady defection of previously centrist voters in Austria could presage a similar scenario, according to Anton Pelinka, professor of political science at Innsbruck University. He says that 'the existing party system stands on the verge of collapse.' Haider's support well exceeds the 13.5 per cent vote garnered two years ago by the Italian National Alliance, the umbrella body that included the neo-fascists. But for Haider to continue attracting new voters he needs to secure a broad respectability that has so far eluded him.

To that end, Haider has begun making efforts to overcome the label 'yuppie fas- cist' he acquired in a 1990 European Par- liament report on racism and xenophobia. `It's no longer necessary for us to call attention to ourselves through an overly, aggressive opposition approach,' he says. `We represent a rational, reasonable alter- native and we do this in a thoroughly mod- erate tone.'

Seeking to emerge from yesteryear's shadow, he talks about his recent visits to the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington and the Simon Wiesenthal Centre's Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles, where his own portrait hangs in a rogues' gallery alongside those of the for- mer Ugandan dictator Idi Amin and Le Pen. 'Today, demagogues continue to exploit racial, religious and national fears,' a wall text there reads. Haider, however, will brook no link with such company and says his party is tempering some long-held attitudes.

For example, he says it is soon likely to scrap its formal commitment to preserving Austria's German ethnic identity. 'We Austrians have now developed such a strong self-identity,' he says, 'that we should not expose ourselves to the misin- terpretation . . . that we somehow want to be part of a greater Germany.' He also points to a series of declarations he has made distancing himself from violence, anti-Semitism and all forms of racial hatred.

But despite his avowed moderation, he seems loath to alienate extremist elements of his following. Take his attitude towards the 1995 yearbook of the Freedom Party's Political Academy in which an essay sug- gests that Jews instigated the second world war. Queried about it, he responds airily, `There would be no need for us to publish a yearbook if we were to censor what indi- vidual authors think and do.'

Marking the 50th anniversary of the war's end this spring, Haider's public state- ments avoided any mention of Holocaust victims and instead urged more financial aid to those who fought in Hitler's army. `In 1945, there were very few people who had reason to rejoice,' he says. He angrily dismisses as 'manipulated' the results of a new Gallup poll conducted for the Ameri- can Jewish Committee which found widespread anti-Semitism and antipathy to other minorities among Freedom Party backers. 'Our largest group of voters are those between 19 and 29 years of age who I dare say don't even know what anti- Semitism is,' he says. 'We have Jewish members. We have Slovene members. We have Croatian members. We have Czech members. We have gypsy members.'

Listening to this litany, I recall how a decade ago Haider rejected characterisa- tion of his party as a successor to the Nazis. `Because if it were,' he asserted then, 'it would have an absolute majority.' Haider's subsequent disavowal of fascism's legacy seems cynical at best. The fact that an increasing number of Austrians regard him as their country's great hope is only likely to add to the EC's anxieties about the newest member of the club.

Previous page

Previous page