Exhibitions

Dynasties: painting in Tudor and Jacobean England (Tate Gallery, till 7 January)

Heads will turn

Martin Gayford

The history of English sculpture in the sixteenth century is a sorry tale.' Thus, discouragingly, begins the Pelican History of Art's treatment of English sculpture in the 16th century. But, if that was the case with the three dimensional arts, what, one can't help asking oneself, are the implications for Dynasties, the new exhibition at the Tate Gallery which deals with painting in Tudor and Jacobean England, 1530-1630? Does Dynasties also tell a sorry tale?

Well, if it's high art you're after, there's

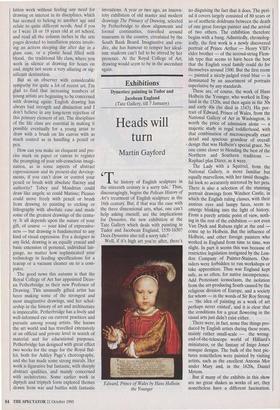

Edward, Prince of Wales by Hans Holbein the Younger no disguising the fact that it does. The peri- od it covers largely consisted of 80 years or so of aesthetic doldrums between the death of one great foreign painter and the arrival of two others. The exhibition therefore begins with a bang. Admittedly, chronolog- ically, the first work is a newly discovered portrait of Prince Arthur — Henry VIII's elder brother — of the second-string Flem- ish type that seems to have been the best that the English royal family could do for themselves around 1500. But the first room painted a nicely-judged royal blue — is dominated by an assortment of portraits superlative by any standards.

These are, of course, the work of Hans Holbein the Younger, who worked in Eng- land in the 1520s, and then again in the 30s and early 40s (he died in 1543). His por- trait of Edward, Prince of Wales, from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, is worth the price of admission alone — a majestic study in regal toddlerhood, with that combination of microscopically exact detail and spacious grandeur of overall design that was Holbein's special grace. No one came closer to blending the best of the Northern and Southern traditions Raphael plus Diirer, as it were.

The Lady with a Squirrel, from the National Gallery, is more familiar but equally marvellous, with her timid thought- ful look so accurately mirrored by her pets. There is also a selection of the stunning portrait drawings from Windsor Castle, in which the English ruling classes, with their anxious eyes and lumpy faces, seem to emerge blinking into the light of history. From a purely artistic point of view, noth- ing in the rest of the exhibition — not even Van Dyck and Rubens right at the end come up to Holbein. But the influence of Holbein, and other foreign painters who worked in England from time to time, was slight. In part it seems this was because of restrictive legislation instigated by the Lon- don Company of Painter-Stainers. Out- siders were forbidden to run workshops or take apprentices. Thus was England kept safe, as so often, for native incompetence. Add Protestant iconoclasm, the isolation from the art-producing South caused by the religious division of Europe, and a society for whom — in the words of Sir Roy Strong — 'the idea of painting as a work of art perhaps never existed', and it is clear that the conditions for a great flowering in the visual arts just didn't exist either.

There were, in fact, some fine things pro- duced by English artists during these years, mainly rather small-scale — the wrong- end-of-the-telescope world of Hilliard's miniatures, or the fantasy of Inigo Jones' masque designs. The bulk of the best pic- tures nonetheless were painted by visiting artists, such as the excellent Antonis Mor under Mary and, in the 1620s, Daniel Mytens.

But if many of the exhibits in this show are no great shakes as works of art, they nonetheless have a different fascination. Once you've forgotten Titian and Michelangelo, the stiffest and most ornate of Tudor paintings can be enjoyed in the same way as naive or, as we now call it, `outsider' art. There is also pleasure to be gained from the sheer eccentricity of some images — the portrait attributed to William Larkin, for example, of Richard Sackville, Earl of Dorset, with huge and gloriously preposterous lace pompoms on his shoes; or the Tate's own portrait of Captain Thomas Lee wearing a mildly embarrassed expression, and, for reasons of symbolism, the bare legs of an Irish foot- soldier.

It is intriguing to discover — from an Isaac Oliver miniature — that Jacobean court ladies wore see-through blouses when acting in masques. The 'Portrait of a Lady, probably Mrs Clement Edmondes', from 1605-10, provides a visual parallel to Shakespeare's poetic obsession with white skin and blue veins. Her chest, revealed by a plunging neckline, is as richly marbled as a ripe Stilton.

Confronted by a roomful of versions of Elizabeth I, I found myself trying to work out what Queen Bess could really have looked like. A recently discovered, and convincingly dowdy, early portrait is a help here. Lucas Horenbout's miniature of a beardless, slab-faced Welsh lager-lout gives a similar clue to Henry VIII before Hol- bein got to work on his image.

Although there are simply too many por- traits and too little of a connecting theme, in diverse ways the exhibition helps one to visualise the past — which is perhaps more an antiquarian interest than an aesthetic one, but an interest nonetheless. To enjoy large tracts of it, however, you have to feel the charm of Englishness in all its perenni- al amateurishness, and dottiness.amateur- ishness, and dottiness.

Previous page

Previous page