Buy the barrel, for peat's sake

Robert Gore-Langton fears running out of his favourite malt

IT's easy enough to buy an expensive malt whisky. But why have a single bottle of the good stuff at the back of the cupboard? Why not have a whole barrel and drink it every day? I went for the cask option back in 1992, when the small Springbank distillery in Campbehown (left at Glasgow and down the Mull of Kintyre) did special fillings for investors and enthusiasts. The cask — a small oak depth-charge — has turned out to be a sensational purchase. A lot of people got burnt in whisky futures around that time, but Springbank, mercifully, was untouched by any scandal.

I went halves on the deal with a dipso barrister friend. Ten years on, our whisky is bulging out of its stays like the Incredible Hulk at about 60 per cent volume, and we are looking at 255 litres (about 360 bottles) of sensational single malt ready to go. Part of the fun of owning a cask is that you also get to choose the barrel it's matured in. Fancy rum and port 'finishes' are all the rage these days, but we went for the trad bourbon (Rebel Yell, I like to think) barrel, though sherry wood is the other usual option.

All we need now is the monstrous amount of duty payable — about a tenner a bottle — to get the stuff home. As they say up north, fookin' bastard Gordon Broon! The only way round the punitive UK tax is to export the whisky under bond to an importer in, say, Calais, pay the duty at the lower French rate, and come back with the paperwork and the cask in a van. But it's a bore and, besides, you don't want to find a blissed-out Bosnian hiding in the barrel when you get back to Dover. The easier method is to bottle a case at a time, cough up the UK duty, and leave the rest to go on improving in the wood for another day. Whatev

er, it's a great way to have your whisky — it makes the perfect present since you get your name on the label — and if you get bored of it, the distillery will buy it back at a good rate. Springbank, alas, has stopped doing casks, and whisky is now almost impossible to get en primeur.

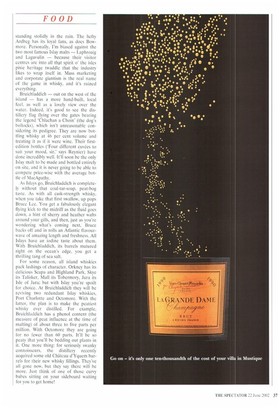

Almost, but not quite. The wine-seller Mark Reynier (readers may know his shop, La Reserve in Knightsbridge, from past Spectator wine offers), who helped to pioneer the Springbank cask wheeze, has gone west to the beautiful island of Islay — home to a bunch of very bored teenagers and one of the planet's sleepiest airports. Reynier and a few friends have pulled off a real coup by buying the mothballed Bruichladdich (pronounced 'brook laddie') distillery from US giant Jim Beam Brands. They've bought the entire stock (the casks go back to 1964), lovingly restored the superb 1881 machinery, tracked down the men that used to work there, and got them back. Bruichladdich is now that rare thing, a privately owned distillery run by obsessives making a pure whisky without computers. That means no caramel colouring, no chill-filtering, local spring water, and casks that mature on site. You can buy anything from a bottle — the ten-year-old is .L23 — to a cask (about 290 bottles) for £775 (01496 850221 or visit www.bruichladdich.com).

Of course, you may wonder why you would want Islay malts at all, since the usual complaint is that they taste as if they belong in a doctor's surgery. It's really a matter of trying the lot. Islay as a whisky region has terrific variety — eight distilleries — and they can be as light as a summer daisy or big, fat, oily beasts standing stolidly in the rain. The hefty Ardbeg has its loyal fans, as does Bowmore. Personally, I'm biased against the two most famous Islay malts — Laphroaig and Lagavulin — because their visitor centres are into all that spirit o' the isles pixie heritage twaddle that the industry likes to wrap itself in. Mass marketing and corporate giantism is the real name of the game in whisky, and it's ruined everything.

Bruichladdich — out on the west of the island — has a more hand-built, local feel, as well as a lovely view over the water. Indeed, it's good to see the dis tillery' flag flying over the gates bearing the legend `Chlachan a Choin' (the dog's bollocks), which isn't unreasonable con sidering its pedigree. They are now bot tling whisky at 46 per cent volume and treating it as if it were wine. Their first edition bottles (Tour different cuvees to suit your mood, sir,' says Reynier) have done incredibly well. It'll soon be the only Islay malt to be made and bottled entirely on site, and it is never going to be able to compete price-wise with the average bottle of MacApathy.

As Islays go, Bruichladdich is completely without that coal-tar-soap, peat-bog taste. As with all cask-strength whisky, when you take that first swallow, up pops Bruce Lee. You get a fabulously elegant flying kick to the midriff as the fluid goes down, a hint of sherry and heather wafts around your gills, and then, just as you're wondering what's coming next, Bruce backs off and in rolls an Atlantic flavourwave of amazing length and freshness. All Islays have an iodine taste about them. With Bruichladdich, its barrels matured right on the ocean's edge, you get a thrilling tang of sea salt.

For some reason, all island whiskies pack lashings of character. Orkney has its delicious Scapa and Highland Park, Skye its Talisker, Mull its Tobermory, Jura its Isle of Jura; but with Islay you're spoilt for choice. At Bruichladdich they will be reviving two redundant Islay whiskies, Port Charlotte and Octomore. With the latter, the plan is to make the peatiest whisky ever distilled. For example, Bruichladdich has a phenol content (the measure of peat influence at the time of malting) of about three to five parts per million. With Octomore they are going for no fewer than 60 parts. It'll be so peaty that you'll be bedding out plants in it. One more thing: for seriously swanky connoisseurs, the distillery recently acquired some old Château d'Yquem barrels for their new whisky fillings. They've all gone now, but they say there will be more. Just think of one of those curvy babes sitting on your sideboard waiting for you to get home!

Previous page

Previous page