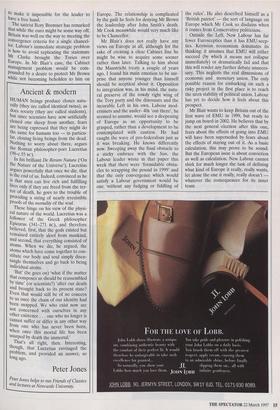

FOR MAJOR VS CLARKE READ BLAIR VS BROWN

Plus Brown vs Cook. Anne IVIcElvoy reveals recent disputes showing that a Labour Cabinet will be split on Europe too

EVERY WEEK, Labour's 'Big Four' (Blair, Brown, Cook and Prescott) meet before shadow Cabinet to set the agenda. Recent discussions in this meeting provide a foretaste of how a Labour inner Cabinet would work and where its strains would lie. Long before the Conservatives pledged to hold a referendum on Europe last summer, Mr Cook made plain his view in the Big Four meetings that Labour should make such a commitment and wrong-foot the government. Mr Blair initially found the idea appealing. Mr Brown did not. Seeing Mr Cook's suggestion as an attempt to wrest control of European policy from him, he blocked it vociferously. In the end, Labour's referendum pledge was made only after the Conservatives had made theirs.

The same happened again a few weeks ago, when Mr Cook worked out — some way ahead of Mr Brown's highly qualified economic team — that monetary union was only likely to go ahead in 1999 if Ger- many fudged the convergence criteria, and that this would give Mr Blair an ideal rea- son for ruling out participation in the first wave. Mr Cook approached Mr Blair privately this time — and at a meeting in the leader of the opposition's cramped offices, told Mr Blair that ruling out Britain's entry to EMU in 1999 would clinch a convincing Labour election victory by putting clear, pink water between the party and the Conservatives on Europe. The move would certainly have forced Mr Major to follow suit, but Labour, for once, would have made the running on Europe.

Again Mr Blair indicated that he was `very excited' by the idea. Again, after con- sultation with Mr Brown, he dropped it. Mr Cook was left with the job of putting across an ambivalent policy which resulted in a muddled statement which suggested that it would be hard for Britain to stay out by 2002 once EMU was up and running. This seems to have been a compromise statement agreed to accommodate Brown's optimism about EMU and Cook's belief that Britain should not join in the first wave. lain Duncan Smith, the quick- witted Tory backbencher dubbed it Labour's `wait and join' policy.

Now that even Chancellor Kohl's most EMU-phile adviser, Karl Lamers, is admit- ting that the criteria are `not written in stone', it seems that once again Mr Cook was right. This week in Bonn, Herr Kohl is facing the final battle with his finance min- ister Theo Waigel, on whether the criteria can be softened to accommodate Ger- many's deficit. It is a battle which he may well lose. The markets are humming with rumours of a postponement of EMU.

There can be few more annoying experi- ences for a clever man than being right and not being seen to be right. For this reason, the shadow foreign secretary Robin Cook is annoyed.

The centrepiece rivalry between Mr Cook and the shadow Chancellor Gordon Brown is becoming the 'Feud of '97' in the way that Brown versus Peter Mandelson dominated Labour in-fighting at Westmin- ster in 1996. Formerly friends and collabo- rators in Scottish politics in the 1970s, the two men are already clashing over whether Britain will participate in monetary union and the shape of Britain's relations with Europe in the next century.

Noddy goes American. The real mystery is why Mr Brown is so reluctant to take even a moderately scepti- cal ine on Europe. He is less of an instinc- tive supporter of integration than Mr Clarke, although he is attracted by the ben- efits of European Central Bank control as a mechanism for saving Labour from itself when it comes to economic management. `The problem', says a former adviser, 'is that Gordon wants to stand up for some- thing in order to underline his own authori- ty in Cabinet. He has chosen monetary union to do it on. If he's not careful, he'll manoeuvre himself to the edge of a precipice in the process.' The signs of strain are also showing on Mr Cook. He possesses a forensic mind but a short temper and vents his frustration in other ways. By a process of Freudian trans- ference, he and Mr Brown have been pub- licly rowing about other things, like the reform of child benefit and the furore of the Tote. At the Tribune anniversary party, Mr Cook produced a hat trick of gaffes, claiming that Michael Foot was 'the best prime minister this country never had', accusing Michael Portillo and John Red- wood of `chauvinism and racism', and rash- ly raising the prospect of a Labour landslide. A young adviser to Mr Brown twitched visibly as Mr Cook's speech ended.

Mr Brown's advisers are rather clumsy in their efforts on their man's behalf — mere freshmen beside the really accomplished spin doctors. They tend to overplay their hand, managing to marry off Mr Brown to the PR consultant Sarah Macaulay earlier this year, an announcement which came as news to both of them.

The same heavy-handedness is evident in their way of dealing with the Brown-Cook feud. Take the newspaper story that Mr Blair was going to create a Ministry for Europe which would oversee Britain's negotiations at the Intergovernmental Con- ference this year, thus wresting responsibil- ity for the process from the Foreign Office. The original leak had it that Peter Mandel- son, Mr Blair's chief strategist, would get the job. But this was deemed unlikely since Mr Mandelson — apart from having a taste for Italian holidays and Parisian weekends — is a novice in foreign affairs. The next version gave the job to George Robertson, the miserable Labour spokesman for Scot- land, appointed chief scapegoat by Mr Blair when his devolution referendum plan unravelled last year. This was so plan* preposterous that there had to have been malice aforethought. `The only reason for placing the stories', says a pro-Cook back- bencher, 'was to rattle Robin.' Mr Blair is adept at anticipating night- mare scenarios. The trouble is that the one he dreads most is the one which, on pre- sent sent form, is most likely to occur, namely Chancellor Gordon Brown becoming to a Labour government what Kenneth Clarke fatally has been to a Tory one: so strongly attached to the goal of monetary union as to make it impossible for the leader to have a free hand.

The satirist Rory Bremner has remarked that while the euro might be some way off, Britain was well on the way to meeting the Convergence criteria for a single chancel- lor. Labour's immediate strategic problem is how to avoid replicating the stalemate Mr Clarke brought the Tories over Europe. In Mr Blair's case, the Cabinet management problem would be com- pounded by a desire to protect Mr Brown while not becoming beholden to him on Europe. The relationship is complicated by the guilt he feels for denying Mr Brown the leadership after John Smith's death. Mr Cook meanwhile would very much like to be Chancellor.

Mr Blair's does not really have any views on Europe at all, although for the sake of creating a clear Cabinet line he might be wise to acquire some sooner rather than later. Talking to him about the Maastricht treaty a couple of years ago, I found his main emotion to be sur- prise that anyone younger than himself should be sceptical about it. Opposition to integration was, in his mind, the natu- ral preserve of the rowdy right wing of the Tory party and the dinosaurs and the incurable Left in his own. Labour mod- ernisers and the under- 40s 'out there', he seemed to assume, would see a deepening of Europe as an opportunity to be grasped, rather than a development to be contemplated with caution. He had caught the wave of pro-federalism just as it was breaking. He knows differently now. Sweeping away the final obstacle to a sticky embrace with the Sun, the Labour leader wrote in that paper this week that there were 'formidable obsta- cles to scrapping the pound in 1999' and that the only convergence which would satisfy a Labour government would be one 'without any fudging or fiddling of the rules'. He also described himself as a `British patriot' — the sort of language on Europe which Mr Cook so disdains when it comes from Conservative politicians.

Outside the Left, New Labour has far fewer Eurosceptics than it has EMU-scep- tics. Keynsian economism dominates its thinking: it assumes that EMU will either succeed (by which it means not collapse immediately) or dramatically fail and that this will render any further debate unneces- sary. This neglects the real dimensions of economic and monetary union. The only possible reason for embarking on such a risky project in the first place is to reach the siren stability of political union. Labour has yet to decide how it feels about this prospect.

Mr Blair wants to keep Britain out of the first wave of EMU in 1999, but ready to jump on board in 2002. He believes that by the next general election after this one, fears about the effects of going into EMU will have been superseded by fears about the effects of staying out of it. As a basic calculation, this may prove to be sound. But the European issue is about conviction as well as calculation. New Labour cannot shirk for much longer the task of defining what kind of Europe it really, really wants, let alone the one it really, really doesn't whatever the consequences for its inner team.

Previous page

Previous page