MORE BULLETS THAN BALLOTS

William Shawcross reports on the violence,

confusion and fear that bedevil Cambodia's attempt at democracy in the face of the Khmer Rouge

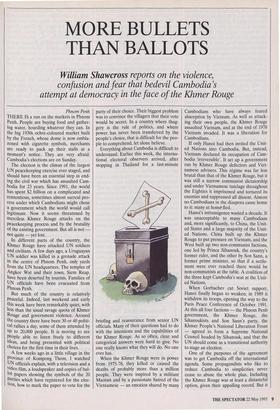

Phnom Penh THERE IS a run on the markets in Phnom Penh. People are buying food and gather- ing water, hoarding whatever they can. In the big 1930s ochre-coloured market built by the French, whose dome is now embla- zoned with cigarette symbols, merchants are ready to pack up their stalls at a moment's notice. They are very afraid: Cambodia's elections are on Sunday.

The election is the climax of the largest UN peacekeeping exercise ever staged, and should have been an essential step in end- ing the civil war which has assaulted Cam- bodia for 23 years. Since 1991, the world has spent $2 billion on a complicated and contentious, sometimes almost surreal pro- cess under which Cambodians might chose a government which the world would call legitimate. Now it seems threatened by merciless Khmer Rouge attacks on the Peacekeeping process and by the brutality of the existing government. But all is not not quite — yet lost.

In different parts of the country, the Khmer Rouge have attacked UN soldiers and civilians. A few days ago, a Uruguayan UN soldier was killed in a grenade attack in the centre of Phnom Penh, only yards from the UN headquarters. The temples of Angkor Wat and their town, Siem Reap, have been deserted by tourists. Families of UN officials have been evacuated from Phnom Penh.

But much of the country is relatively peaceful. Indeed, last weekend and early this week have been remarkably quiet, with less than the usual savage quota of Khmer Rouge and government violence. Around the country there have been 30 or 40 politi- cal rallies a day, some of them attended by up to 20,000 people. It is moving to see People able to listen freely to different ideas, and being presented with political Choices for the first time in their lives.

A few weeks ago in a little village in the Province of Kompong Thom, I watched UN officials explain, with a television and a video film, a loudspeaker and copies of bal- lot papers showing the symbols of the 20 parties which have registered for the elec- tion, how to mark the paper to vote for the

party of their choice. Their biggest problem was to convince the villagers that their vote would be secret. In a country where thug- gery is the rule of politics, and where power has never been transferred by the people's choice, that is difficult for the peo- ple to comprehend, let alone believe. Everything about Cambodia is difficult to understand. Earlier this week, the interna- tional electoral observers arrived, after stopping in Thailand for a last-minute briefing and reassurance from senior UN officials. Many of their questions had to do with the intentions and the capabilities of the Khmer Rouge. As so often, clear and categorical answers were hard to give. No one really knows what they will do. No one ever has.

When the Khmer Rouge were in power from 1975-78, they killed or caused the deaths of probably more than a million people. They were inspired by a militant Maoism and by a passionate hatred of the Vietnamese — an emotion shared by many Cambodians who have always feared absorption by Vietnam. As well as attack- ing their own people, the Khmer Rouge assaulted Vietnam, and at the end of 1978 Vietnam invaded. It was a liberation for Cambodians.

If only Hanoi had then invited the Unit- ed Nations into Cambodia. But, instead, Vietnam declared its occupation of Cam- bodia 'irreversible'. It set up a government run by Khmer Rouge defectors and Viet- namese advisers. This regime was far less brutal than that of the Khmer Rouge, but it was still a narrow communist dictatorship and under Vietnamese tutelage throughout the Eighties it imprisoned and tortured its enemies and suppressed all dissent. Almost no Cambodians in the diaspora came home to it: many at home' fled.

Hanoi's intransigence wasted a decade. It was unacceptable to many Cambodians and, more significantly, to China, the Unit- ed States and a large majority of the Unit- ed Nations. China built up the Khmer Rouge to put pressure on Vietnam, and the West built up two non-communist factions, one led by Prince Sihanouk, the country's former ruler, and the other by Son Sann, a former prime minister, so that if a settle- ment were ever reached there would be non-communists at the table. A coalition of the three kept Cambodia's seat at the Unit- ed Nations.

When Gorbachev cut Soviet support, Hanoi finally began to weaken; in 1989 it withdrew its troops, opening the way to the Paris Peace Conference of October 1991. At this all four factions — the Phnom Penh government, the Khmer Rouge, the Sihanoukists and Son Sann's party, the Khmer People's National Liberation Front — agreed to form a Supreme National Council headed by Sihanouk, and that the UN should come as a transitional authority to stage an election.

One of the purposes of the agreement was to get Cambodia off the international agenda. Some propagandists who like to reduce Cambodia to simplicities never cease to abuse the whole plan. Including the Khmer Rouge was at least a distasteful option, given their appalling record. But it

was the only way of getting international agreement and, in fact, it marginalised the Khmer Rouge. It stripped them of their place at the UN and, even more important, it separated them from their principal sponsors, the Chinese. In exchange for the Khmer Rouge being given a seat on the Supreme National Council, the Chinese agreed to stop arming them. They have apparently abided by that promise.

There are different layers of UN effort here. Fifteen thousand troops and 5,000 civilian police have been sent to help impose human rights and democracy. Many of them come from countries — Ghana, Nigeria, Indonesia, China — where such commodities are in short supply. The sol- diers have been restricted by the peace- keeping (as opposed to peace- enforcing) terms of the mandate. Many of the police have seemed more interested in whoring and drinking and fast driving in the UN's white cars than in protecting people.

On top of the men in uniform is a layer of 5,000 international civil servants, many of whom come from comfortable UN offices in New York and Geneva. Their union insisted on a daily allowance of $145 — about the same as the annual income of the subsistence farmers which most Cam- bodians are. Under the Paris Agreement these administrators were supposed to take control of the key government ministries and the provincial authorities: they have not been able to do so.

Even so, the UN has successfully pro- moted ideas of human rights, particularly in Phnom Penh. There are several Cambo- dian human rights organisations, attracting many members. There is a free press for the first time, with several lively and com- bative Cambodian papers, and the excel- lent English language Phnom Penh Post. The UN has created a kind of political springtime, in the capital at least.

The heroes and heroines of this entire operation have been the UN volunteers, who are paid only some $700 a month. Recruited from around the world and often young, it was they who, with Cambodian teams, went out into the furthest marches of the countryside and registered about 95 per cent of the available electorate to vote at the end of last year. Now they are sup- posed to oversee the actual voting as well, and they are scared, as well they might be.

The uppermost UN layer of all is occu- pied by just two men — Yasushi Akashi, the Secretary-General's Special Represen- tative, and John Sanderson, the Australian force commander. They must feel very lonely. Akashi, a decent and clever serving UN official, decided that he should not be a MacArthur but must approach Cambo- dia's internecine politics in an Asian way, eschewing confrontation. Sanderson agreed.

The key moment came last June, when the Khmer Rouge broke the accords and refused to allow the UN into their areas to disarm their troops and register their peo-

ple to vote. Akashi and Sanderson opted for discretion rather than valour.

The French general with the UN advance party, Michel Lofidon, argued that they should instead have sent troops at once into the Khmer Rouge areas to enforce the Paris Agreement. But — and this is a problem central to all such UN operations today — both Akashi and Sanderson were warned by their own gov- ernments in Japan and Australia that casu- alties amongst the UN troops (which would certainly have followed an assault on Khmer Rouge strongholds) would risk the collapse of support at home and the with- drawal of the troops. And indeed the death of one Japanese policeman two weeks ago caused near hysteria in Japan.

The UN's failure to disarm the Khmer Rouge means that no one was disarmed. Cambodia is inundated with weapons (especially, hideous anti-personnel mines) and awash with violence. Six months ago, the main opposition party, Funcinpec, run by Prince Norodom Ranarridh, son of Sihanouk, was the favourite to win the election. Since then government agents have murdered or wounded over 100 of its officials and many UN officials think that the people will now be too terrified to vote against the regime.

There is a madness about the Khmer Rouge but, unfortunately, it is a Cambodi- an madness. In March I saw the quickly made coffins of the children of Vietnamese fishermen being brought to the banks of the Great Lake. They had been murdered by the Khmer Rouge who claim that there are still 2 million Vietnamese in Cambodia. That is fantasy (half a million settlers might be accurate) but many Cambodians would accept the figure.

When Boutros Boutros Ghali was in Phnom Penh in April, the Khmer Rouge representative to the Supreme National Council, Khieu Samphan, said to him, 'The whole world can see that we are right about the Vietnamese in Cambodia.' Boutros Ghali said no, no one saw it. He was correct — except in Cambodia where hatred of Vietnam is so widespread that such Khmer Rouge massacres are almost popular. There is a myth, propagated most assidu- ously by John Pilger, that western policy and the whole UN peace plan have been designed to legitimise the Khmer Rouge and help them back to power. This is shameful nonsense. The ten-year Viet- namese occupation is the principal reason why peace has been so elusive here. And the peace plan has in fact left the Khmer Rouge more isolated than ever, cut off at last from their principal sponsors and armourers, China.

In a secret speech in early 1992, Pol Pot told his lieutenants that in 1991 Bush had told Sihanouk that America was 'absolutely opposed to the Khmer Rouge', would stop them winning elections, and that the UN `have a clear objective, namely to eliminate the Khmer Rouge presence in Phnom Penh'.

Last month Akashi made a blistering attack upon the Khmer Rouge at a meeting of the Supreme National Council in Phnom Penh. Khieu Samphan was visibly flustered and could hardly speak. Two days later his delegation fled the town. He asked Sihanouk to convene another SNC meeting in China but then the Khmer Rouge did not appear.

As this weekend's election looms, there are still far more questions than answers. Will the Khmer Rouge attack so many polling stations that the election is called off? Or will they just try to disrupt it so extensively that they can thereafter claim that it was a farce? Would the government itself accept a defeaS? After the election, the new constituent assembly has three months in which to approve a constitution and appoint a gov- ernment. The Khmer Rouge will undoubt- edly try to provoke chaos. They will say that the only solution is for Sihanouk to override the results and create a govern- ment of 'national reconciliation' which includes them. And, astonishing though it may seem, many Cambodians will agree with them. There is such an exhaustion from war and such a longing for peace.

While understandable, it seems to me that the hope for peace with the Khmer Rouge is naive. It is hard to know just what their real strength now is. The optimistic assessment (to which I still incline) is that they are much weaker than their frightful reputation and behaviour suggest and could, over years, be defeated by an effec- tive government with an army built up by perhaps France or Australia. But is such a government conceivable in Cambodia? That is quite another matter.

This week in Phnom Penh only one things seems certain: the elections are a stage, not an end in themselves. The Paris Peace Plan has not brought peace or recon- ciliation as it was supposed to: perhaps it never could. The international effort has been costly and painful and many of its ambitions remain unfulfilled. But Cambo- dia would have been in far worse shape without it.

Previous page

Previous page