A night at the opera

Peter Phillips

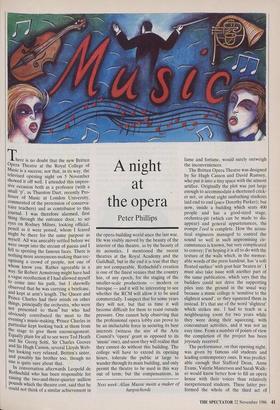

here is no doubt that the new Britten Opera Theatre at the Royal College of Music is a success; nor that, in its way, the televised opening night on 5 November showed it off well. I attended this impres- sive occasion both as a professor (with a small 'p', as Thurston Dart, recently Pro- fessor of Music at London University, commented of the pretension of conserva- toire teachers) and as contributor to this journal. I was therefore alarmed, first thing through the entrance door, to set eyes on Rodney Milnes, looking official, pencil as it were poised, whom I feared might be there for the same purpose as myself. All was amicably settled before we Were swept into the stream of guests andI i

fell to spotting the famous faces. There is nothing more anonymous-making than rec- ognising a crowd of people, not one of whom know you. Rather agreeable in a way. Sir Robert Armstrong might have had a vague recollection if I had allowed myself to come into his path, but I shrewdly observed that he was carrying a briefcase, and kept at arm's length. The Queen and Prince Charles had their minds on other things, principally the orchestra, who were not presented to them- but who had obviously contributed the most to the evening's s music-making. Prince Charles in particular kept looking back at them from the stage to give them encouragement. Equally plain for all to see were Ted Heath and Sir Georg Solti, Sir Charles Groves and Sir Hugh Casson, several Lloyds Web- ber looking very relaxed, Britten's sister, and possibly his brother too, though no one is quite sure about that.

In conversation afterwards Leopold de Rothschild who has been responsible for raising the two-and-three-quarter million pounds which the theatre cost, said that he could not think of a similar achievement in the opera-building world since the last war. He was visibly moved by the beauty of the interior of this theatre, as by the beauty of its acoustics. I mentioned the recent theatres at the Royal Academy and the Guildhall, but in the end it is true that they are not comparable. Rothschild's creation is one of the finest venues that the country has, of any epoch, for the staging of the smaller-scale productions — modern or baroque — and it will be interesting to see whether the RCM will allow it to be used commercially. I suspect that for some years they will not, but that in time it will become difficult for them to resist outside pressure. One cannot help observing that the professional opera lobby can prove to be an ineluctable force in securing its best interests (witness the size of the Arts Council's 'opera' grant as opposed to its `music' one), and soon they will realise that they cannot do without this building. The college will have to extend its opening hours, tolerate the public at large to wander through its main building, and only permit the theatre to be used in this way out of term; but the compensations, in fame and fortune, would surely outweigh the inconveniences.

The Britten Opera Theatre was designed by Sir Hugh Casson and David Ramsey, who put it into a tiny space with the utmost artifice. Originally the plot was just large enough to accommodate a shortened crick- et net, or about eight sunbathing students laid end to end (pace Dorothy Parker); but now, inside a building which seats 400 people and has a good-sized stage, orchestra-pit (which can be made to dis- appear) and general appurtenances, the trompe l'oeil is complete. How the acous- tical engineers managed to control the sound so well in such unpromising cir- cumstances is known, but very complicated to convey; I'm hoping it is all to do with the texture of the walls which, in the memor- able words of the press handout, has 'a soft floated surface' with goat hair 'beaten in'. I must also take issue with another part of the same publication, which says that the builders could not drive the supporting piles into the ground in the usual way because a music college is 'sensitive to the slightest sound', so they squeezed them in instead. It's that use of the word 'slightest' which strikes me. I had to teach in a neighbouring room for two years while they were doing their squeezing, with concomitant activities, and it was not an easy time. From a number of points of view the completion of the project has been joyously received.

The performance, on that opening night, was given by famous old students and leading contemporary ones. It was predict- able enough that Stafford Dean, Anne Evans, Valerie Masterson and Sarah Walk- er would know better how to fill an opera house with their voices than relatively inexperienced students. These latter per- formed the whole of the third act of Britten's A Midsummer Night's Dream, led by Denis Lakey as Oberon and Gerald Finley as Bottom. These two were almost as good as any old-hand; but I was slightly surprised that their colleagues could not project themselves more convincingly in this relatively small place with perfectly clear acoustics. They need practice, and it is for this that the college should be reluctant to throw the place open to the commercial world. For the moment they are surely right to preserve it exclusively for the use of the students, and thus ready, if necessary, to play it as a trump card in the next tiresome round of the Centres of Excellence competition.

Previous page

Previous page